South Africa

Op-Ed: Even today, Ahmed Timol’s torture case sounds frighteningly familiar

The inquest into Ahmed Timol’s death is important in the context of South African history as it provides an opportunity for us to understand the sacrifices past generations have made for this country so that we may improve it today. However, it also forces us to look at the use of torture in post-apartheid South Africa. By AZARRAH ABDUL KARRIM.

Last Monday marked the 2017 International Day in Support of Victims of Torture, which commemorates the numerous victims of torture around the world.

It was also the 33rd anniversary of the 1984 Convention against Torture and Other Inhumane or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, ratified by 162 Member States of the United Nations (UN), including South Africa, which ratified the treaty in 2013.

The post-apartheid South African state has a strange and strained relationship to national and international anti-torture legislation. As Carolyn Raphaely writes in her 2015 article, in 2010 the UN Human Rights Committee decided that South Africa had violated the torture convention (as well as the UN Convention on Civil and Political Rights) when in 2005 they ruled on an individual case that was part of a larger case of 231 inmates at St Albans Prison who were brutally tortured by warders.

Human rights attorney Egon Oswald represented the torture survivor, Bradley McCallum, in Geneva, where the Human Rights Committee resides. South Africa was ordered to prosecute those responsible for his torture.

This should resonate deeply with South Africans who are burdened with a violent past of detainment and torture of freedom fighters and citizens at the hands of the Security Branch.

The very same Monday also marked the opening of the Ahmed Timol inquest at the South Gauteng High Court. Timol was a member of the South African Communist Party and an anti-apartheid activist who was detained in 1971 at the infamous John Vorster Square (now Johannesburg Central Police Station).

He was arrested on 22 October 1971 and died in detention five days later. His death was ruled a suicide when magistrate JJL de Villiers, presiding over the case, found that Timol had jumped out of the 10th floor window of John Vorster Square.

However, upon inspection during the post-mortem, wounds all over his body associated with torture were found, but this was ignored by the magistrate in his ruling.

After Timol’s death, his mother Hawa Timol testified before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in 1996 and described what she had witnessed when she received her son’s body. She said his face was covered in blood, with wounds all over his body that were not yet healed. Mrs Timol pleaded with the TRC to reopen the case. But no officials involved in the incident were subpoenaed and she was left with an unbearable pain to carry until her death the following year.

Ahmed Timol’s nephew, Imtiaz Cajee, was five years old at the time. As an adult, he decided to dedicate most of his life to finding the truth. It took many years for Cajee to find the forensic evidence, eyewitnesses and other evidence needed to reopen the case and get the attention of the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA).

Forty-five years after his demise, the inquest seeks to uncover the real cause of Ahmed Timol’s tragic death.

Timol’s friend and anti-apartheid activist, Dr Salim Essop, was arrested with Timol and also held at John Vorster Square.

Essop told the court on Tuesday about his ordeal. During his interrogation, he was suffocated with a plastic bag, they made him squat and then “mule kicked” him against his thighs, they administered electric shocks, and he was dangled upside down from the 10th floor of the dreaded building. On one occasion the security police administered an unknown drugs which Essop thinks could have been LSD or a “truth serum” to make him talk.

By the time Essop was taken to hospital, he said in his testimony, “I was in a state of near death, I would say I was in sort of a coma […] I had felt like life was going out of me.”

Essop is one of a few people who are testifying at the inquest, and one of thousands of South Africans who were taken to detention and tortured during apartheid.

The inquest is important in the context of South African history as it provides an opportunity for us to understand the sacrifices past generations have made for this country so that we may improve it today. However, it also forces us to look at the use of torture in post-apartheid South Africa.

The Wits Justice Project (WJP) communicates with countless inmates who claim they are being tortured during their time in prison. They tell us about dog attacks, electroshocks, assault, and lengthy periods in an isolation cell.

Although most people see torture as a thing of the ugly past, it is still very prevalent in police stations and prisons throughout South Africa. Ruth Hopkins and Marche Arends, in an article for the Daily Maverick published in 2016, describe just how prevalent torture is. They write, “[e]very day, South African police officers and prison wardens go to work, armed with legal tools that can be used to torture. Electric shock devices, tonfas, pepper spray and rubber bullets are classified as non-lethal weapons and therefore are assumed to be a safer alternative to guns.”

The statistics are equally telling. In the Independent Police Investigative Directorate (IPID) 2015/2016 Annual Report it is noted that 3,509 cases of assault in police stations were reported and 145 cases of torture. However, only two police officials have been prosecuted for torture under the new act, according to IPID. A R500 and R12,000 fines were imposed, a seemingly quite lenient punishment, given the serious nature of the crime. The Judicial Inspectorate for Correctional Services (JICS) in their 2015/2016 annual report documented 811 cases of assault by prison officials on inmates and 15 torture allegations. There have been no known prosecutions of prison warders.

In an article published in the Mail & Guardian in 2015, Hopkins details the alleged torture tactics by warders at G4S-run Mangaung Prison – infamous for its violence.

She writes, “[The] WJP revealed the results of a year-long probe into the prison. It uncovered a practice, since the inception of the prison in 2000, of alleged routine assaults, electroshocking, alleged forced injections with anti-psychotic drugs and lengthy isolation of inmates in the prison. The allegations were based on interviews with approximately 70 inmates and dozens of wardens, governmental reports and audio and video footage of the forced injections and the electroshocking.

Hopkins further reveals that prisoners had been tortured to death in very similar ways to Timol’s. Hopkins writes about Isaac Nelani, an inmate who according to four eyewitnesses as well as the pathologist died a very suspicious death. It was ruled a suicide by the company.

In 2005, Nelani made the mistake of simply asking for an extra blanket on a cold day. According to the eyewitnesses, Nelani was brutally beaten, electroshocked and then beaten some more. They saw prison warders drag Nelani to the “dark room”, which was ironically set up as a soundproof suicide prevention unit but had become the prison’s torture chamber. Nelani never made it out of the dark room.

A BBC interview with an Emergency Security Team (EST) member working for G4S confirmed that there was a “dark room” where inmates were tortured, much like apartheid-style detention facilities such as John Vorster Square.

These are just some of the chilling similarities between detention during apartheid and the actions of police and prison officials now. The only difference is that before political activists were tortured; now any offender is susceptible to torture in prison or by the police. Based on these stories it seems that after more than two decades of democracy we have not moved any closer to an end to torture in prisons and police cells. DM

Azarrah Abdul Karrim is a journalist with the Wits Justice Project (WJP) based in the journalism department of the University of the Witwatersrand. The WJP investigates miscarriages of justice and human rights abuses related to the criminal justice system.

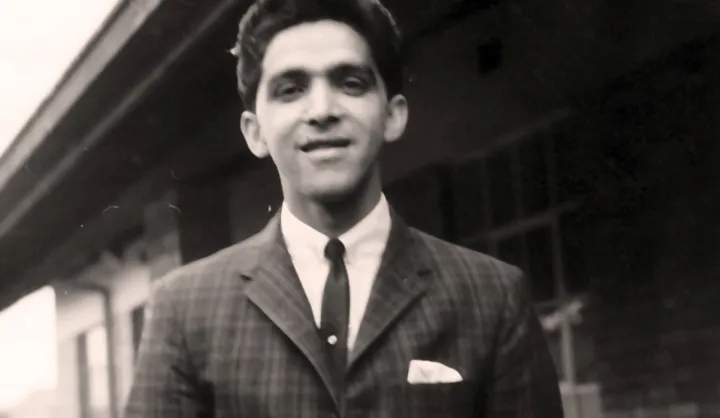

Photo: Ahmed Timol.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider