Apparition I

The year 1973, according to George Packer, was when the American Century arrived at the beginning of its drawn-out end. The Unwinding, Packer’s award-winning diagnosis of the nation’s current malaise (published 2013), argued that as soon as the Middle East oil embargo coincided with the US reaching peak oil, the conditions were in place for the whole thing to unravel. The “whole thing” here was the Roosevelt Republic, which for almost half a century had delivered the institutions and structures that allowed Americans to go to bed secure in the knowledge that God loved them—if they could trust in their bosses to protect their jobs, and if they could trust in their bankers to protect their savings, all was right with the world. But in 1973, with hardly anyone paying attention, the trust was broken. “The void,” wrote Packer, “was filled by the default force in American life, organised money.”

In December 1974, in a recording studio in Minneapolis, an appliance salesman's son bent into a microphone and summed up in three lines what Packer would one day take the length of a book to say. “Now everything’s a little upside down, as a matter of fact the wheels have stopped/ What’s good is bad, what’s bad is good, you’ll find out when you reach the top/ You’re on the bottom...”

Since the release of “Idiot Wind”, the fourth track on the 1975 album Blood on the Tracks, the rest of us have been playing catch up. Bob Dylan, born Robert Allen Zimmerman on 24 May 1941, had intuited the future in that song, which perhaps was why he’d gift-wrapped it in imagery redolent of the visionary works of William Blake and Saint John the Divine. In the second verse there’s a “lone soldier on the cross, smoke pourin’ out of a boxcar door”, while the third verse has a priest wearing black on the seventh day, a guy sitting “stone-faced” as a building burns.

No longer, it seems, are we talking about the undoing of Roosevelt’s promise to every white male Christian citizen of America. Out in prophet country, where only one writer/poet in every three or four generations gets access, the fates of nations do not count as fit subject matter for artistic treatment. In this realm, a nation is only useful for the insight it grants to the collective human soul, and so Dylan must be writing about damage on a much grander scale. The building burning on the seventh day? Welcome to the apocalypse.

Either that, or as Bob’s son Jakob Dylan once suggested, “Idiot Wind” is a song about his parents fighting.

Apparition II

The year 1987, according to the BBC, was when the world’s Cold War superpowers vowed to reverse the damage done by the nuclear arms race. On 8 December of that year, after a three-day summit in Washington, US President Ronald Reagan and his Soviet counterpart Mikhail Gorbachev put their signatures on the Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces Treaty, which aimed to destroy all medium- and shorter-range nuclear weapons capable of hitting European targets.

Reagan termed the signing of the treaty the realisation of “an impossible vision”, while Gorbachev said it had “universal significance for mankind”.

Dylan, meanwhile, was about fifteen months away from laying down these lyrics: “We live in a political world/ Where peace is not welcome at all/ It’s turned away from the door/ To wonder some more/ Or put up against the wall”. Today, instead of being remembered as the American president who defused the global nuclear threat, Reagan is the guy who created a planet on which the rich get massive tax breaks, labour unions have no teeth, job security has given way to outsourcing, and African nations are forced to import American-bred mutant poultry. Gorbachev, for his part, is remembered as the guy who provided the inspiration for the Klingon Chancellor Gorkon in Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country.

And so Dylan was spot-on when he reverted on the 1989 album Oh Mercy back to his true and original milieu, being prophecy in the biblical idiom: “Ring them bells St. Peter/ Where the four winds blow/ Ring them bells with an iron hand/ So the people will know/ Oh it’s rush hour now/ On the wheel and the plow/ And the sun is going down/ Upon the sacred cow”.

Either that, or “Ring them bells” is nothing more than a sweet bucolic scene, the folk music equivalent of a nineteenth century farm novel.

Apparition III

The year 2006, according to the company’s own CEO Lloyd Blankfein, was another year amongst many in which investment bank Goldman Sachs proved its mettle as a mainstay of virtue in the long and difficult saga of human progress. As Blankfein wrote in the foreword to the bank’s 2006 annual report: “We believe strongly that Goldman Sachs, through the skill and know-how of its people, is contributing to the development of vibrant and dynamic markets that can efficiently allocate capital to their most productive use.”

A few years later, despite its leading role in causing “vibrant and dynamic markets” to crash around the world, Goldman Sachs would be bailed out by the American taxpayer to the tune of $10 billion—a rescue package that allowed Blankfein himself to net a 2008 bonus of $42-million, which he justified to the public by saying that he’d been “doing God’s work”.

Again, from a realm outside time, Dylan saw the divine significance. His 2009 track “Beyond here lies nothin” is believed to be a riff on a 2,000-year-old quote from Ovid, a line that goes in full, “Beyond here lies nothing but chillness, hostility, frozen waves of an ice-hard sea.” Ovid was writing about exile, a subject dear to any prophet’s heart, and Dylan’s take on the line was to show that in the end we’re all exiles—even the super-rich, who won’t be taking any of it with.

“I love you pretty baby/ You’re the only love I’ve ever known/ Just as long as you stay with me/ The whole world is my throne/ Beyond here lies nothin’/ Nothin’ we can call our own.”

Either that, or love, like subprime mortgage-back securities, is a complicated and impossible scam. DM

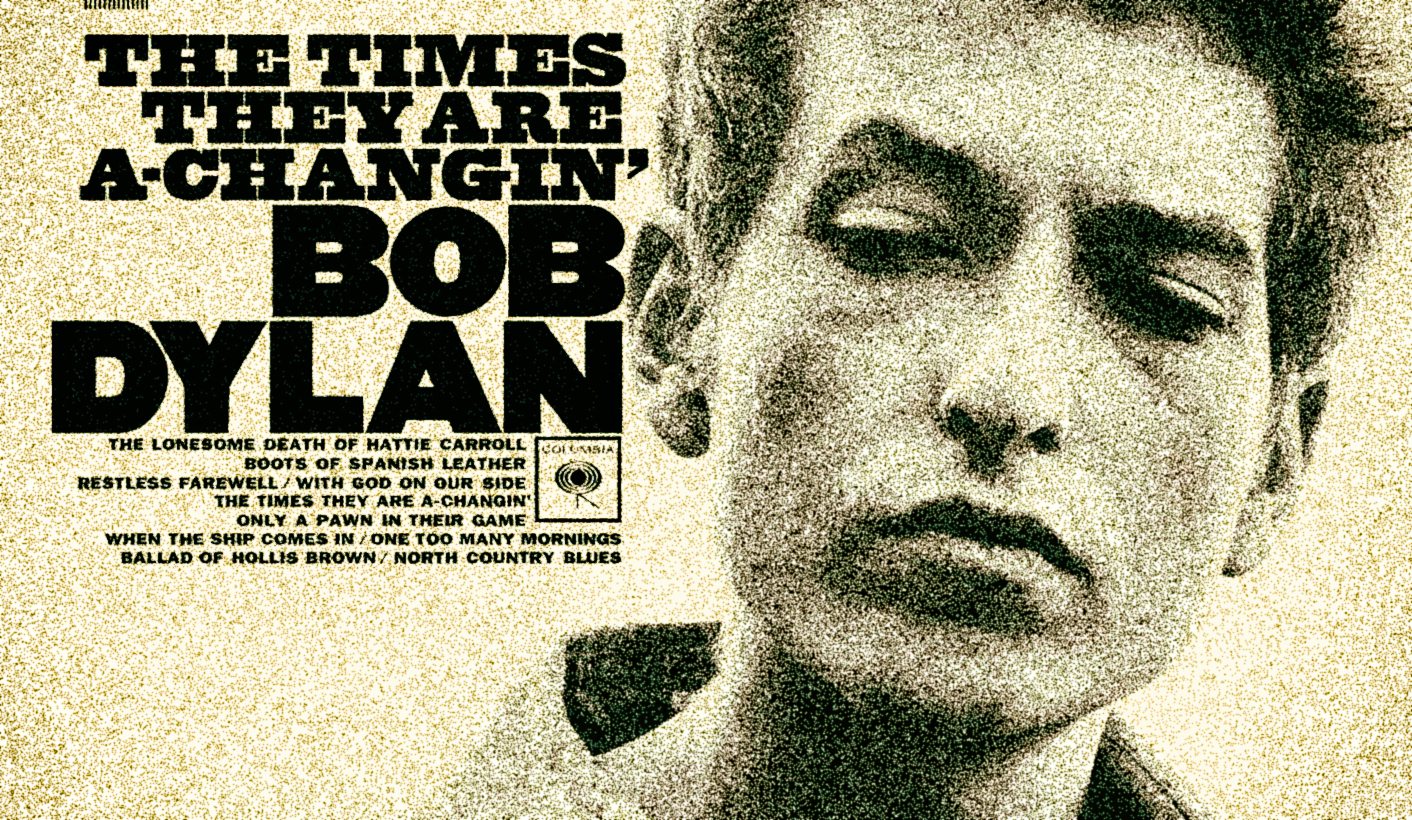

Photo: Dylan's The Times They Are A-Changin' 1964 album cover.