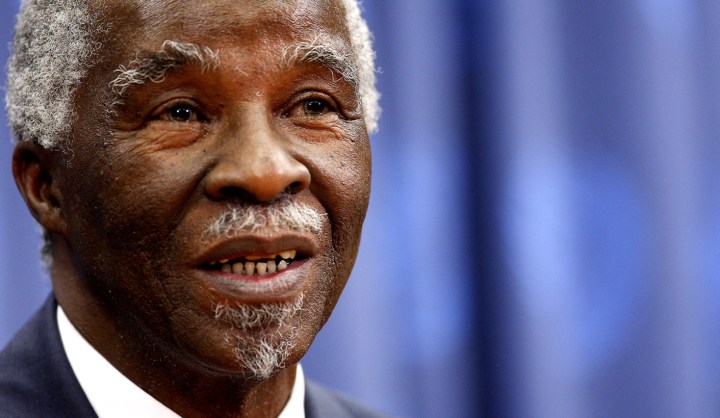

South Africa

The Temple of Mbeki: The things we’ve forgotten to forget

South Africa now has its own presidential library, dedicated to holding everything from the papers to an old passport belonging to Thabo Mbeki. This is where his history will be housed. More disturbingly, writes RICHARD POPLAK, it’s where his history will be made. Welcome, then, to Temple Mbeki.

I want you to think of a library as a place of forgetting. But here’s what you’ll need to remember in order to forget: in April 1997, South Africa’s then-Deputy President Thabo Mbeki proclaimed the dawn of an African Renaissance. His speeches to this effect remain some of the greatest ever delivered by an African statesman—they were luminous odes to limitless possibilities. They were also melancholy indictments of our many missteps.

“The harbingers of death and the victims of their wrath,” said Mbeki, “are as African as you and I”.

The deputy president was not just addressing Africans, but everyone – in those heady days of his political ascendancy, his notion of what constituted an “African” was capacious. This was the unfurling of a new African epoch, and it was precisely Mbeki’s intention, standing as he was on the threshold of the 21st century, to punch some life into a discourse that was mired in the politics of victimhood, abjectness, and shame.

“Those who have eyes to see,” intoned Mbeki, “let them see. The African Renaissance is upon us. As we peer through the looking glass darkly, this may not be obvious. But it is upon us.”

The idea of a continental Renaissance was hardly new; it was first evinced by the Senegalese Pan-Africanist intellectual Cheikh Antaw Diop in a series of essays collected in Towards the African Renaissance: Essays in Culture and Development, 1946-1960. When Mbeki re-upped the re-upping, he was speaking three years after Africa’s last colonial regime had fallen. The continent was whole, and wholly African – the idea seemed once again of its time.

The Renaissance speeches were midwifed by a departmental paper written by Mbeki and his inner circle, called ‘The African Renaissance: A Workable Dream’. The document was meant to form the cornerstone of the New South Africa’s foreign policy, and it was based on the presumption that post-colonial history unfolded in three phases. The first began with the liberation struggles following the Second World War, culminating in independence and the development of a socialist “brotherhood” of states. The second began with the end of the Cold War, when socialism was discarded for what Mbeki described as the “surgence of more open political and economic interaction on a world scale” – in other words, neoliberalism imposed from outside due to the collapse of African economies in the 1980s. These were, however, mere “dress rehearsals” – Mbeki’s words – for the main show: African nations situated on the global stage “as equal and respected contributors to, as well as beneficiaries of all the achievements of human civilisation”. With Africa fully integrated into the international community, Mbeki believed that the world would “rediscover the oneness of the human race”.

The deputy president’s rhetoric proved influential; he counted US President Bill Clinton among his many acolytes, all of whom loved the fact that most of what he said sounded like a U2 lyric. “A renaissance is an historical moment whose many elements will develop independently,” Mbeki reminded his audience. “It cannot be simply be decreed or conjured up like a spell but will arise on the basis of a certain minimum factors. However, without an integrated programme of action to build upon those minimum factors, the dream of the renaissance shall forever be deferred.”

That last line, a reference to the classic Langston Hughes’s poem, bore an implicit warning. What happens to a dream deferred? the poet wanted to know:

Maybe it just sags

like a heavy load

Or does it explode?

***

Mbeki did not, of course, usher in an African Renaissance. Instead, he left us with a very heavy load, as well as all the nitro, glycerin and matches we required to answer Hughes’s final, ominous question in the affirmative. The statist-tinged neoliberal South Africa Mbeki built as a gift to us locals, and as a blueprint for the rest of the continent, has not soared, but nor has it descended into chaos. Instead it ticks along, shrinking as it grows, divided and unequal – an insidious tweak on what came before. Mbeki was a tragically flawed character, his brilliance undone by a fundamental misreading not only of the limits of the guided-but-open State, but also by the shallowness of his humanity. Mbeki did not believe in people. He believed in ideas.

It should therefore come as no surprise that his latest idea is a home for his ideas. The bookish ex-president, who was said to carry libraries around in his head, is now preparing a library here on earth. The Thabo Mbeki Presidential Library, or TMPL (pronounced “temple”), was introduced to the media earlier this week by its executive director and curator, Dr Buhle Mbambo-Thata. Along with former first lady Zanele Mbeki – and we must certainly employ American honorifics when discussing a presidential library, that most American of institutions – Mbambo-Thata showed reporters around the first phase of the project, housed in the Kgorong Building on Unisa’s Muckleneuk campus. Eventually, according to Mbambo-Thata, a standalone facility costing tens of millions of rand will be built to house the books, papers and arcana that will put Mbeki’s reign in a wider “context”.

How much wider? “We want to provide a space to reflect on the processes and realities which have created the conditions where Africa is today and to be able to confront the question: Where should Africa be tomorrow?” asked Mbambo-Thata. So it goes with Mbeki – any attempt at discovering the man should include a deeper investigation into the state of the African continent, a geopolitical entity that bares Mbeki’s stately imprimatur.

A library, so far as I understand the word, refers to an unguided and uncurated repository of knowledge. So we should probably tag TMPL with a more appropriate noun – museum, perhaps, or maybe shrine. And like most museums or shrines, its didactic panels, whispering docents and high priests will guide us toward a certain set of conclusions. What might those be? Mbeki the statesman is bigger than Mbeki the man, and grander than the country that so pointedly threw him from his corner office like yesterday’s garbage. If Africa has risen in the last 20 years – and it has – then the personage who hopes to be the intellectual face of that rise has made a declaration: Mbeki is the portal through which 21st century Renaissance Africa is not only located, but realised.

When the temple – sorry, library opens to the public next year, it will find the former president all but rehabilitated. Long after he alienated his fanboys by fiddling with the ontology of the Aids epidemic (whatever one thinks of that scandal, it was pure Mbeki – he made Aids about him); long after he ceded the ANC to the forces of patronage and corruption; long after he used lamb’s wool instead of steel wool to clean up Zimbabwe’s land reform debacle; and long after he left office as a sclerotic leader kept alive by a small cabal of insiders and their 24/7 tongue-baths, Mbeki lives again.

During the Mandela memorial at FNB Stadium in December of last year, President Jacob Zuma was booed, while Mbeki was cheered. Due to some inexplicable political calculus understood only by them, the Democratic Alliance hails the Mbeki era as a Willy Wonka-ish time of happiness and light. No one would expect a mining company to engage in a thorough historical appraisal of a former CEO, and what is South Africa but the Ur-mining company, home to 50 million diggers, gold-panners and short-term claim holders? Here, our national ritual is amnesia, and any history that hasn’t been commodified – that hasn’t been bought and sold as a stately museum or a t-shirt – is subject to reinvention.

Mbeki, like so many who create presidential libraries, will try, by careful inclusion or elision, to write his own history. This is his very own Choose Your Own Adventure book. And while he has many helpers in his revisionist project, his most important collaborator is the terrible work the speed of contemporary life does to our collective memory. Time shrinks, and while we insist on forgetting the specifics of the past, we also require a past to look back – a past that works as a salve for having no past

“The nostalgic desires to obliterate history and turn it into a private or collective mythology, to revisit time like space, refusing to surrender to the irreversibility of time that plagues the human condition,” wrote Svetlana Boym in The Future of Nostalgia. Like the Swiss medical student who first coined the term in the seventeenth century, Boym considers nostalgia a disease. For societies, she acknowledges, the disease can prove fatal.

And in order to speed us along our suicide-by-nostalgia track, Zanele Mbeki visited presidential libraries across the United States. “What I learned about presidential libraries,” she told the Mail & Guardian, “is that they tell their president’s story. Some presidencies are very controversial but what is important is for him [Mbeki] to tell his story. There’s Aids, there’s Zimbabwe, there’s this, there’s that … this is where he can tell his story.”

There’s this, there’s that. In between, there’s some stuff that happened. For those who are serious about history’s unseriousness, and for those who understand the palliative effects of providing a past for those who have forgotten their own, there are presidential libraries. For the rest of us, there are the exquisite, empty pleasures of pretending to remember, and TMPL will serve as a temple to the things we’ve forgotten to forget. DM

** Richard Poplak is the author of “Until Julius Comes“, a comprehensive, irreverent take on the 2014 SA National elections.

Photo: Thabo Mbeki, then President of South Africa, speaks during a news conference at the United Nations headquarters in New York April 16, 2008. REUTERS/Chip East

Become an Insider

Become an Insider