The most prominent blurb on the back of Jonathan Franzen’s new essay collection Farther Away is the one that reads: “There are about twenty great American novelists in the generations that follow me. The greatest is Jonathan Franzen.” If you were playing a literary parlour game and had to guess the author of this glistening encomium, there would be only one name to fit the bill. That’s because he is the sole surviving member of the quartet that for many years was recognised by male American booklovers as the greatest of the generation that preceded Franzen’s.

Philip Roth was for close on half a century lumped with Saul Bellow, Norman Mailer and John Updike as a paterfamilias of modern American letters. Part of the blame for this fell on Updike himself, the only gentile in the bunch, who through his brilliant yet self-conscious prose nurtured an ongoing feud with the three Jews (Updike’s “Bech” books are nothing if not a metaphorical attack on the Semitic pretenders to his WASP throne). More than Updike, however, it was a group of vocal and accomplished feminist theorists, incensed by the objectification of women in the combined works of the foursome, that served ironically to fortify their reputation.

In late December 2009, almost a year after Updike’s death, two years after Mailer’s, and four-and-a-half years after Bellow’s, an influential piece appeared in the New York Times that revisited these old animosities. Written by NYU cultural commentator Katie Roiphe, the article argued that the explicit and transgressive sex scenes in the older generations’ books—the orgies, the anal sex, the intimations of violence—had been replaced in a younger generation of male novelists by ambivalence, trepidation and touchingly failed consummations.

Wrote Roiphe: “The same crusading feminist critics who objected to Mailer, Bellow, Roth and Updike might be tempted to take this new sensitivity or softness or indifference to sexual adventuring as a sign of progress (Mailer called these critics “the ladies with their fierce ideas.”) But the sexism in the work of the heirs apparent is simply wilier and shrewder and harder to smoke out. What comes to mind is Franzen’s description of one of his female characters in The Corrections: ‘Denise at 32 was still beautiful.’ To the esteemed ladies of the movement I would suggest this is not how our great male novelists would write in the feminist utopia.”

So it was both appropriate and incongruous, only a few months before the last living king’s abdication, that the imperial touch of his sword should land on the eager shoulders of Mr Franzen. And making it even more appropriate and incongruous was the fact that master and student had been engaged for some years in a feud of their own, the younger man consistently voicing his distaste for the elder’s “self-indulgent excesses” and “thin female characters”. This fight was at its most heated in 2010, when Franzen’s Freedom was going head-to-head on the new arrivals shelves with Roth’s Nemesis, and pummeling it a million ways from sideways.

Of course, all of that ended this year with Roth’s public and somewhat unprecedented passing of the mantle onto Franzen, and Franzen’s repayment by naming Sabbath’s Theater among his top five “most influential” books ever. “Whole chunks of Sabbath's Theater can be safely skipped,” America’s new Greatest Novelist wrote, “but the great stuff is truly great: the scene in which Mickey Sabbath panhandles on the New York subway with a paper coffee cup, for example, or the scene in which Sabbath's best friend catches him relaxing in the bathtub and fondling his (the friend's) young daughter's underpants.”

Personal hypocrisies aside, the author knew exactly what the precedents were to that little snippet he penned for Time magazine. Roth’s 1995 masterpiece was hailed by many of the giants of US criticism, including Harold Bloom and James Wood, as a monumental work, and its evocation of the impulses that shape the male libido are widely regarded as amongst the most powerful in contemporary literature. While it was natural and correct that dissenting critics such as Michiko Kakutani would call the book “distasteful and disingenuous,” it nevertheless stays true to a dark masculine urge that is, when all is said and done, an inescapable reality. For this, it won the US National Book Award for Fiction.

Thirty-five years earlier, Roth had won his first National Book Award, for the collection Goodbye, Columbus. Thanks to this remarkable debut at the age of 26, the New Jersey native was branded a “self-hating Jew” by his more righteous co-religionists. Roth responded in 1969 by achieving worldwide fame with a novel about a Jewish adolescent who uses an uncooked piece of liver as a surrogate vagina, an editorial decision that answered for good any lingering doubts about his standing as a mensch. Still, 43 years after publication, Portnoy’s Complaint continues to help oversexed young men feel less alone, if not exactly less ashamed.

Roth’s other most celebrated books, including 1997’s American Pastoral (winner of the Pulitzer Prize), 2000’s The Human Stain (winner of the UK’s WH Smith Literary Award), and the Zuckerman series (published from 1979 to 1985 and collected as Zuckerman Bound) all play to some extent on the themes of sexuality and Jewish and American identity. But their strength lies is in how they transcend localised questions of tribe and nationality to arrive at revelations about human nature that are universal. It’s not for nothing that Roth has long been known as the best American novelist never to have won a Nobel.

In an interview published on the weekend, Roth said that he made the decision to stop writing a few months after finishing his last novel, Nemesis, about a 1944 polio epidemic in his hometown of Newark. “I didn’t say anything about it because I wanted to be sure it was true,” he said. “I thought, ‘Wait a minute, don’t announce your retirement and then come out of it.’ I’m not Frank Sinatra. So I didn’t say anything to anyone, just to see if it was so.”

Unfortunately, it is so. The author of 31 books, the man who wrote standing up at a dais for ten hours a day, the hermit who lived in a remote hideout in the Connecticut woods and only visited the city when he absolutely had to, is no longer perfecting his sentences and restructuring his chapters in slavish devotion to his inner demons.

For some, perhaps justifiably, this news will come as a welcome epistle. But for those of us who grew up shouting aloud in triumph at the primal energy of his paragraphs, it’s as if the world has just been diagnosed ever so slightly impotent. DM

Read more:

- “The Naked and the Conflicted,” in the NY Times

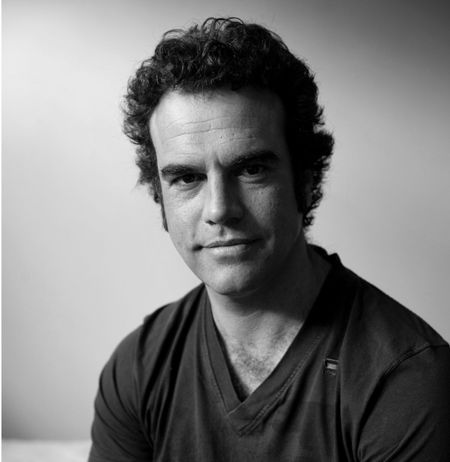

Photo: Novelist Phillip Roth waits to be presented the 2010 National Humanities Medal by U.S. President Barack Obama in a ceremony in the East Room of the White House in Washington March 2, 2011. REUTERS/Larry Downing