Zeacks and Jackson are friends. They first saw each other on the bus from Klerksdorp to Marikana when they were hired by Lonmin more than a year ago. They saw each other again at the training centre, and a nod led to a few words. They found that they shared the same language, isiXhosa, and did the same work – they are rock drill operators. They were assigned to the same shaft, and a friendship began.

They live across a metre-wide dirt strip from each other, in corrugated zinc one-room shacks, part of a compound of 10 rooms that share a pit latrine. The rooms have no electricity; they use paraffin lamps and paraffin stoves.

When I first went with Zeacks to his home, a massive hailstorm broke the winter drought and the dirt passageway outside his room swiftly became a muddy pool. I had to balance between broken blocks of cut granite stepping stones and a narrow concrete sill running along the front of the shacks to get to his room. In the downpour, the roof above his bed, which dominates the room, leaked profusely, causing him to scramble for his washbasin.

Every work day – Monday to Friday and two Saturdays a month – Zeacks and Jackson get up well before first light and wash in plastic basins balanced on old beer crates. Their girlfriends make them tea on the paraffin stove, served with a thick slice of bread.

They join the trickle of men from shacks scattered in little communities all across the meagre bushveld, the trickles gradually becoming a river of men and women as they near the entrances to the various shafts and plants that make up Lonmin’s Marikana platinum operation.

Many of the workers wear white overalls with strips of reflective safety tape. “As a driller you have to wear an overall, a white overall, so all can see you from a distance, as it is dark underground,” says Zeacks. The company issues them one white overall every six months.

Underground, at the rock panel and in the development tunnels, water is sprayed constantly and mud is everywhere.

“At the working place, as a driller, we use water, drill with water. Automatically, it’s going to be wet, the whole of your body is going to be wet,” Zeacks says. “We also use grease – black grease, pure black grease, if you know what’s grease, on a white overall.”

Sometimes, Jackson finishes what Zeacks has started telling me. Then Zeacks will add a thought or a detail to what Jackson says. Their narrative blends into a single tale, a story of men working underground and of living above it in primitive conditions.

Photo: Zeacks and Jackson's compound where they live in single rooms, and share a common pit latrine with other tenants. There is no water. Marikana, North West, South Africa. September 9, 2012. (Greg Marinovich)

At the end of their shift, which is between eight and 12 hours, the overall is caked in the black grease. They trudge home as night sets. The next day, they have to once again report at the shaft wearing clean white overalls.

To wash a white overall caked in machine grease in a basin of cold water is no trivial matter.

“We wash them with our bare hands, take cold water and wash them. They will never be white because of the stains, that black stain. It doesn’t get clean like it was. Even if you take a brush and you scrub it,” Zeacks says. “We usually soak it first two hours long and then wash it, with a scrubbing brush, scrub it.”

They wash the overall up to three times to get it clean. Each time, they leave it to soak while they go fetch another 25 litres of water. They estimate it takes three to four hours to wash the overall.

If they were to use it as management says, at the rock face, they would spend their lives washing it. Or buy an extra three to four overalls. So the miners quickly learned to take old clothes with them to the rock face. They strip off the overalls once they are at their workstation, hang them up and slip into the old clothes they leave underground.

The problem of the white overall is not what led drillers to organize the Marikana strike in August. It is simply one of the difficulties they have to contend with. The real grievances the drillers have with Lonmin are far more integral to their core working conditions.

The working conditions of rock drillers like Zeacks and Jackson vary widely across shafts and even within a shaft at Lonmin.

“In Karee we have three divisions,” says Jackson. “Eastern, Western and Karee. At these three we are working the same jobs but they don’t treat us like each other.”

The standard work crew at a working rock panel consists of a driller, an assistant driller, a malaisha (“shovel boy”) and a chisaboy (assistant miner).

At Karee, the drillers work without an assistant. They explain, in relays, what Zeacks faces at the rock panel without an assistant. The drilling machines they operate are huge, with drill bits, which they call drill sticks, of 1.2 to 1.5 metres long.

The miner paints Xs on the rock face where the holes have to be drilled. It is where the explosives have to be packed by the assistant miner, the chisaboy.

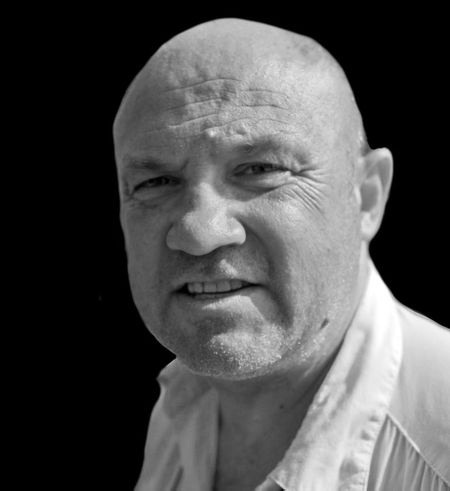

Photo: Zeacks in his single corrugated zinc room. Marikana, North West, South Africa. September 6, 2012. (Greg Marinovich)

Zeacks adds that they also have a lot of equipment, from hoses to extra sticks, and when he finishes drilling, it is the assistant driller who is meant to help him carry all the gear.

“If we drill here, we are supposed to take it all back outside, so when they blast it is not damaged. You take it everyday from this place to another, every morning and when you knock off you are supposed to take it again to safe place.”

The first difficulty is in starting the hole, in placing the point of the drill stick exactly on the miner’s mark. The vibrating, spinning drill tends to skitter off the mark, so without an assistant to hold the tip at the right place, the driller has to use one hand at the front of the bit, and the other control the handle at the rear. He is stretched out, and if his glove is caught in the spinning drill bit, he can be badly injured.

Sometimes the drill sticks break, with grave consequences when the driller’s face is alongside the spinning metal.

Another reason drillers like to work with an assistant is that the high pressure of the water that jets along the drill bit, as well as the vibrations, tend to loosen the rock. An assistant can keep an eye on the hanging rock above then, and warn the driller if it looks about to fall on them. Alone, he just has to risk it.

The rock panel that Zeacks works in is exactly 1.2 metres high. That means he spends his drilling time bent over at the waist. I imagined that forcing the drill into the rock was much like me drilling into a cement wall at home – that it takes a lot of effort to drill in. Yet the design of the drilling machine actually has a support that helps push it in, and once the drill stick has bitten into the right spot, the driller just has to control the machine.

The difficult part, they tell me, is when they have drilled in deep enough and they have to extract the drill stick. Now the mud and rock are holding the bit, and dislodged rock presses down on it.

If the driller switches off, the bit will never be extracted. This is the most difficult part, as the driller has to pull back, with all of his strength to, while bent over double.

Most nights, when Zeacks gets home, he needs his girlfriend to knead his back before he can walk straight.

Zeacks works in stoping, leaving behind an open space after the ore has been removed, while Jackson works in development.

“We drill the way where the work of the panel starts. We make a direction... if the platinum is up here I am supposed to go there to make a road for those coming behind us. “

Most of the time, Jackson works upright. The tunnel he makes is not as low as Zeacks’, but he has other difficulties. His drill stick is 3.4 metres long, the drilling machine he has to control is more than twice his height.

Jackson also works without a drilling assistant. He describes how he has to sometimes drill upwards, struggling to control the vibrating machine and its long bit on his own.

“When I finish drilling there I take out the machine and put it backwards there, I’m supposed to take the explosive, put it there,” he says.

I query this, does he really do the mining assistant’s job too? He places the explosives?

“Yes exactly. I do that job, they say that is the law at Lonmin. No chisaboy here in development at Lonmin.” In fact, Jackson has no malaisha either. He does the job of the miner, because otherwise the work would never finish – the miner has to work on five or six different stopes, often far apart.

Yet the drillers at the Lonmin shafts that work alone are not paid a cent more. The way they see it, if they must work alone and endure the extra hardship and dangers, they deserve at least a portion of the savings the mine is making on not using an assistant driller.

Photo: Zeacks re-lives his Small Koppie horror. (Greg Marinovich)

This situation has arisen because of their union, the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), and not in spite of it. I would have thought a union would have fought tooth and nail for their members. Surely, the union’s responsibility is to improve working conditions and to get more dues-paying members. The four jobs Jackson does underground could be parlayed into at least two more workers – potential union members.

“Our union betrayed us,” says Jackson. “They come with the papers, and told us to just sign it like that in morning. It was written in English, the shift boss told us to all attend the meeting. He said, ‘All of you here, just sign it.’ What they make us to sign there, I didn’t understand it.”

“The union betrayed us,” Zeacks adds. “We are in this deep, deep trouble because of these guys driving those Land Rover cars, X5s, getting a living wage. Someone just sitting in an office outside there gets maximum wage. That’s why those guys are forcing us to go to work because all of them are in the gravy train. We just suffer.”

What drives the miners is the promise of bonuses. They have to meet targets that will allow them to get bonuses. Yet, there seems to be some chicanery around this. They receive bonuses only three months out of 12, and these seem to rotate among the teams working underground. The miners claim that mine and shift bosses get bonuses every month, yet collude to deny the crews extra earnings.

And still they are proud to be employed at Lonmin. They are especially proud of belonging to that exclusive group of RDOs, the rock drill operators.

“We are the men, the real men, not sissies,” Zeacks explains. “You are a man if you are a driller, if you are not a driller, you are a sissy man. You are a strong man if you are a driller. Most of the Sothos, they say you don’t drink with them if you’re not a rock driller. Malaishas are not man enough to drink with them.

“In olden times, our fathers who were working in the mines were recognised as being drillers. You could see this one was a driller.” Drillers, Zeacks claims, could be discerned walking down the road – they were heavily muscled, big men. “They were paid a good salary, the value of the Rand was still good and they were getting a lot of money above other people. They were getting better wives and cherries.” Drillers worked hard and ate well; they always had money in their pocket.

Neither Zeacks nor Jackson is a large man. Jackson weighs 62 kilograms, Zeacks looks about the same.

They say the value of their salaries is far less, comparatively, to that what drillers earned in the old days. “Now less pay, working a heavy job, lots of stress and now we are thin. We earn peanuts.”

This means that they can’t afford meat every day; they will never become the big bruisers that were the old time drillers.

And while they are renowned as tough men who always have money to flash around, they tell me that rock drill operators have to avoid enjoying the ladies and the booze. One or the other is OK, but not both. “Booze – do it only weekends. And ladies – make it to do one of those two. If you do both, you will drill for six months and give up, because this job is just too heavy.”

When Zeacks and Jackson went to the place they call Thaba, and we know as Wonderkop, outside the Marikana plant on 16 August, they say they were expecting to get a positive response to their wage demands from Lonmin management. Indeed, this is why so many had gathered there that day, on their hill, because they believed their demands were about to be addressed.

Instead, as envoy after envoy returned from Lonmin without any answers at all, it became clear that management was not about to discuss anything with them.

Police gathered in larger numbers, then rolled out the razor wire in what looked to them like a move to block access to the shanty town of Nkaneng.

The miners’ leadership was down at the wire, speaking with the police, and soon they were giving hand signals that the strikers should decamp. They began to move off the hill, they wanted to be free of the razor wire encircling them, but they were not too concerned.

As Jackson would say afterwards, he had been in such strikes before and fully expected the police to use teargas, water cannon and even rubber bullets. It was what the miners were prepared to deal with.

Zeacks was separated from his friend, and recalls that “there was the Hippo which was brown in colour, and there were, I don’t know, soldiers, in camouflage uniform, like soldiers wear. That one started shooting with real ammunition, then we started running back towards the big hill, they chased us. We were chased by the bullets and many were hit. One was run over by a Hippo, I saw the one who was run over, his whole body was flat; he was run over by the Hippo.”

Even then, it seems Zeacks was not overly concerned. The miners started to regroup, to sing their songs and defy the cops, but the water cannon and the teargas forced them back.

“We ran towards that side, we were lighting fires to diminish the teargas. It was now hectic as there was shooting from all sides, and the helicopter was shooting from above. We thought if we got in the trees it was not easy for them to shoot from above. So we ran to those rocks there (at Small Koppie). There was a curve in the rock where you could sneak into. The bullets were flying over our heads, hitting on the rocks. It was protecting us.”

But then police began closing in on them, on foot. Some wore camouflage uniforms strikingly similar to those used by the notorious Koevoet counter-insurgency unit in South West Africa in the ’80s and by riot police in the townships in the ’90s.

“There were others that were coming on the foot now, and as they came, we grouped in one place. Everyone wanted to be beneath the other ones, so that he could not be shot easily. Most of them were on top of me, only my head was out, and then three policemen came from this side, and others were shooting from this side.”

Then, he says, one man said to the others, “Let’s surrender, gents, let’s surrender.” He stood up, with his hands raised, and he was immediately hit in the hand by a bullet. He fell, but again said, “Let’s surrender,” and stood. That was when he was hit in the stomach. He struggled up a third time, and was hit in the thigh. He collapsed and tried to crawl to safety. Zeacks does not know if he survived.

There was another man alongside him, who then also stood, hands raised in the universal signal of submission. He was shot in the head and fell.

“By that time we were afraid now to stand up and surrender, because we were seeing that the cops shooting at the people whilst they were trying to surrender,” Zeacks says. “Three cops came through the bushes were holding guns like this. They were dressed in police uniform, the usual police uniform, having this bulletproofs and police berets and they were using the big guns. The other one was having the gun on the thigh. One waved a hand to those who were shooting from the Hippo. I think it is the sign to stop shooting.”

The gunfire finally ceased, and the police yelled at them, “Out, out, move out, move out!”

As they moved out they trampled on fellow miners underfoot, the miners did not move. They may have been dead, or not.

The police made them lie on their stomachs. “They did not want to you to raise your head, if you did they hit you with the back of the gun. I think they did not want us to recognize them, or see their faces.

“You will see there is a lot of shit there, people use it as a toilet, but we moved on top of that, right through to the lorries.”

While awaiting arrest, they were searched – and beaten. They were also told that they were cop killers, and they were going to die. One policeman told them that if this were Zimbabwe, they would simply pour petrol on them and burn them as they lay there.

Zeacks was one of some 270 striking miners arrested, and who would be charged with the murder of his own colleagues through the “common purpose” doctrine.

Jackson did not seek shelter at Small Koppie, but instead zigzagged his way across the veld. He, too, heard policemen say they were now going to kill them.

At one stage, one of the fleeing miners called out to the others to lie down, as they would not then be shot. Jackson did, and saw a police Hippo or Nyala drive over a man’s head. Another miner then used his cell phone to photograph the corpse.

When Jackson finally made it home, he asked Zeacks’ girlfriend if Zeacks had made it back. He had not, and Jackson feared the worst. He fell into a deep, exhausted sleep.

When Zeacks was finally released from police custody, on 5 September, the friends met up again. Yet the strike dragged on, and the memories of what they had seen haunted them. They had no counselling, but as Zeacks says, “we counselled each other, in jail, talking about what had happened.”

Six weeks after the strike began, Lonmin finally came to the table with an offer. It was not as much as the miners had asked for, but then they never expected to have their initial demands met. It was meant to be a negotiation.

Zeacks and Jackson are both back at work at Lonmin, with a 22% increase in their salaries. Their work conditions have not changed, they still strip off the safety overalls for ragged clothes, and they still do the work of three to four men underground.

The crisis is not yet over, just abated. DM

Main photo: Zeacks (right) and Jackson (left) at their compound where they live in single rooms. North West, South Africa. September 9, 2012. (Greg Marinovich)