The best reason to read the biography of Keith Richards (amongst a bunch of very good reasons) is that you get to breathe for a moment the crisp and bracing air that keeps the most powerful of our rock gods eternally young. Life, as the memoir is memorably titled, has you flipping every few pages back to the front jacket, where Keef grins at you in glorious testament to his 68-year-old youth: Yeah mate, he seems to be saying, I’ve found the elixir, and its name is rock ‘n roll.

Yet to witness a Bruce Springsteen performance is to know this one sublime truth: the life juice reserved for the Stones axe-man is a notch or two down in quality from the pristine product consumed by The Boss. Leaving aside the drugs and the booze and the fracture lines on the face, Richards, who can still own a stage like few guitarists on earth, has never matched as a sexagenarian the punch of the 62-year-old from Long Branch.

Take, for instance, the temperature inside the Palais Omnisports de Paris-Bercy on Wednesday night: over 100 degrees Fahrenheit. Take the initial reaction to the heat of the Parisian crowd: whiny. Take Springsteen’s demeanour throughout the uninterrupted three-hour twenty-minute set: breathtakingly vital.

From the opening track, “We Take Care of Our Own,” the first single off his new Wrecking Ball album, to the absolute bloody final encore after the final encore, the faux-Irish ditty “American Land,” the singer-songwriter was going like a piston on his strings, like a formula one mechanic on his set list changes, and like a rally driver on his footwork (actually, more like a football midfielder, given the amount of times he covered the length and breadth of the stage).

Mostly, though, his energy went into his lyrics: and here, as has come to be expected of the man, it was in the sincerity of the message that the force was felt. Like much of Wrecking Ball, for which Springsteen’s current tour is named, “We Take Care of Our Own” is an anthem to the American working class, an ironic yet heartfelt paean to the masses sidelined by the greed of corporations and the expediency of conservative politicians.

After all, since 1984, when Springsteen publicly castigated President Reagan for failing to notice the underlying narrative in songs like “Born in the USA” (Reagan, it will be remembered, attempted to piggyback on the artist’s Main Street cred in an attempt to whip up some re-election fervour), few Republicans have dared attach his name to their cause.

But that doesn’t mean Springsteen is no longer misread—what else to say about almost 20,000 French fans belting out the chorus to “Born in the USA,” which came second in the seven-track encore, even if the main reason for playing it was because it was the 4th of July, and even if Springsteen introduced the smash hit by saying, “France was America’s friend before America was America”?

Of course, as JM Coetzee once noted, you have to allow people their misreadings; an observation that is especially trenchant when considering the overriding fact about Springsteen’s biggest singles: their peerless earworm quality. Because there were, I can testify, a few South Africans belting out the chorus too.

Meaning that now, inevitably, we have arrived at that famous line that everyone erroneously attributes to Elvis Costello: “Writing about music is like dancing about architecture.” In other words, how to simply dig the experience and unpack it at the same time? To the rescue can only come a writer of the class of Greil Marcus, who in 1985 was both beautiful and lyrical in his definition of an album that had long since become seminal in the annals of rock: Born to Run.

“Springsteen's songs—filled with recurring images of people stranded, huddled, scared, crying, dying—take place in the space between 'Born to Run' and 'Born to Lose', as if to say, the only run worth making is the one that forces you to risk losing everything you have,” Marcus wrote.

“Only by taking that risk can you hold on to the faith that you have something left to lose. Springsteen's heroes and heroines face terror and survive it, face delight and die by its hand, and then watch as the process is reversed, understanding finally that they are paying the price of romanticising their own fear.”

More pedestrian music journalists lean heavily, by contrast, on connections to make an article work. In the spirit of the genre, here’s one such connection: on 4 July 1954, exactly 58 years before Bruce Springsteen brought his Wrecking Ball Tour to Paris, three men got together in a studio to record an album—one of them was a 19-year-old Memphis trucker by the name of Elvis Presley, and the event was arguably the most important turning point in the evolution of modern American music.

Watch: Bruce Springsteen - Because The Night - Darkness On The Edge Of Town - Paris July 4th 2012

Another critical turning point came in August 1975, when Springsteen, who had first been inspired to take up music at the age of seven after watching Presley on the Ed Sullivan Show, was booked to play ten gigs at the tiny Bottom Line club in New York. It was a few weeks before Born to Run was due for release, and Springsteen’s label, Columbia, invited industry insiders to come see what this New Jersey boy and his E Street Band could do.

“Springsteen and the E Streeters roared through two-hour performances,” noted Rolling Stone magazine, “varying the set list for the most part, but always making sure to include the show's emotional centrepiece: a gripping version of ‘Thunder Road,’ performed as a solo by Springsteen at a piano. ‘The band hadn't learned to play that song real well,’ says Springsteen. ‘That's the only reason I did it solo.’”

On Wednesday night in Paris, the E Streeters played every song well, which goes without saying, given how long they’ve been at it. The memorable songs from Born to Run included the eponymous title track, which first helped Springsteen reach mainstream popularity—a direct result of his breakout performances at the Bottom Line—and “Tenth Avenue Freeze Out,” which has closed the show 32 times since the tour began in Atlanta on 18 March.

At the first of the two shows at the Palais Omnisports de Paris-Bercy, “Tenth Avenue Freeze Out” was the penultimate song in the set, and included near the middle an impeccably timed moment of silence to Clarence Clemons, the E Street Band’s tenor saxophonist who died last year. Regrettably, there was no “Thunder Road” solo on the piano, and neither were there any solos off The Ghost of Tom Joad (the superb 1995 album musically and lyrically reminiscent of Nebraska).

What there was, however, was a piano solo of “Independence Day,” originally released on Springsteen’s fifth album, The River. The lyrics are characteristically dark, and follow the story of a home that can no longer hold the father and the son. The third and final chorus, which was recited word-for-word by a surprisingly large chunk of the audience, goes like this:

“So say goodbye it's Independence Day/ Papa now I know the things you wanted that you could not say/ But won't you just say goodbye it's Independence Day/ I swear I never meant to take those things away.”

And then The Boss jumped off his piano stool, and the E Street Band—consisting of an accordionist, a violinist, two drummers, three back-up vocalists, three guitarists and five members of the brass section—fired up again and segued seamlessly into “The River”.

Springsteen, at 62, was the vital force at the centre of it all, the same magnificent presence he was when he was “discovered” in 1975 at the age of 26, the same New Jersey boy he’s always been; just more refined, more superbly aged, more transcendent. DM

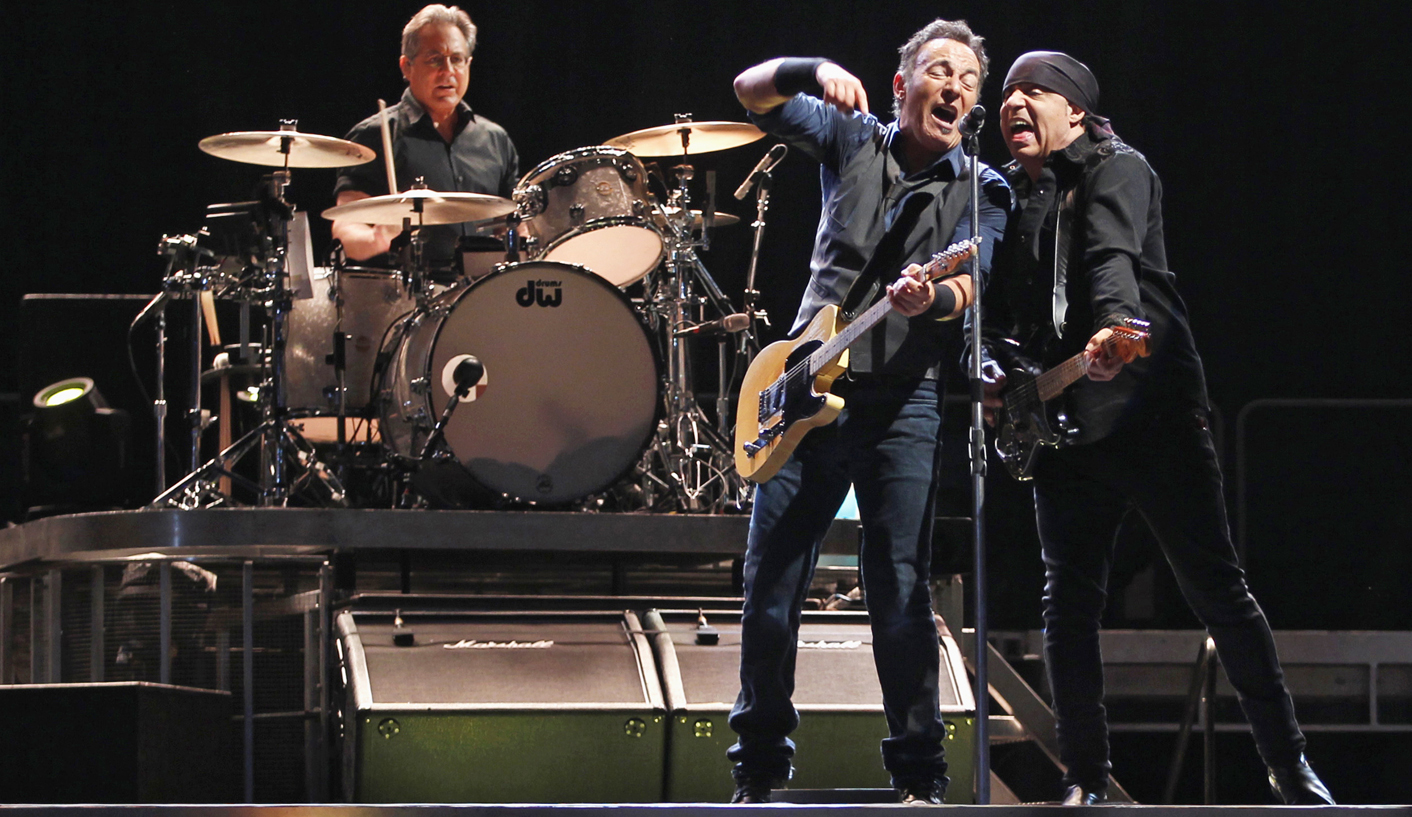

Photo: Bruce Springsteen (C) performs with guitarist Steve Van Zandt and drummer Max Weinberg (L) of the E. Street Band during the European tour to promote their latest album "Wrecking Ball" at Palau Sant Jordi stadium in Barcelona May 17, 2012. Picture taken May 17, 2012. (REUTERS/Gustau Nacarino)