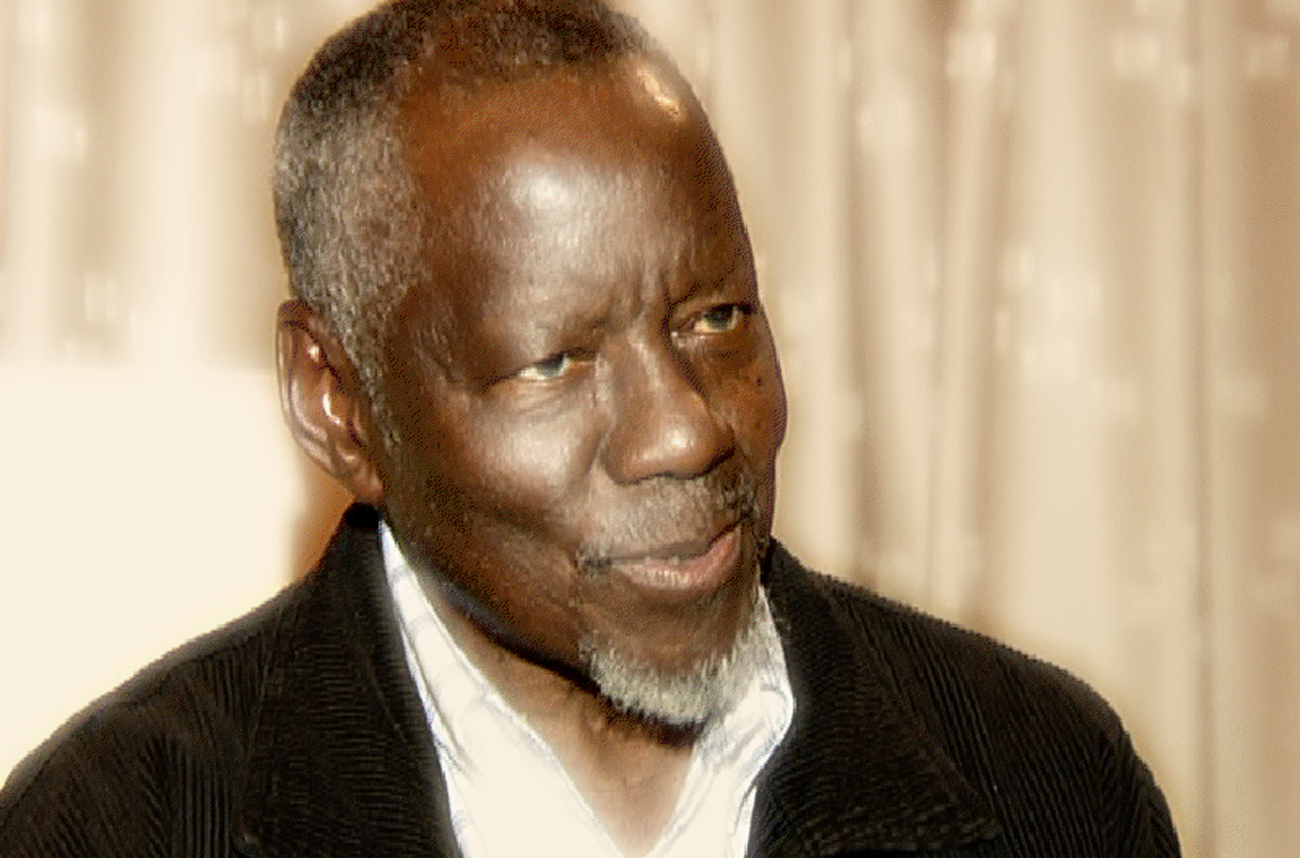

Sam Nzima has told this story many times. The words he speaks have the rhythm of an oft-repeated nursery rhyme. Or a prayer.

“I was just shooting, I didn't have a sense of what pictures I was taking... But something told me that I needed to protect these pictures. So I took the film and hid it in my sock. The police did stop me... they ripped out the film I had put in my camera and exposed it to the light. But the film in my sock, they didn't see that...”

In his sock, Nzima had stashed what would become the most iconic image of apartheid-era brutality ever recorded: the picture of a dying Hector Pieterson being carried in the arms of his screaming friend.

Photo by Sam Nzima.

The man who shook the world with that image chose not to make his home in a big city. He returned to the tiny rural village of Lilydale, near Bushbuckridge, where he was born. If he travels the world talking about taking photographs in apartheid-era South Africa, he returns to a place ravaged by poverty. One that, for the last eight months, has been without running water.

“It's very difficult to live in a place where you don't have water. It's a quite long time that we don't have water here. It's very difficult,” Nzima says.

“We just survive on hiring vans to go and fetch water from the other place. You have to pay somebody to go and fetch water for you.

“The hard part is that we have got a French drain, we have got a toilet inside of our house, we can't flush it. We've got to get water by buckets and put on the toilet tank to flush the toilet. It's very difficult and when you get up in the morning, you must get running water, hot water and have a bath. But you can't do that. You just warm the water with a bucket, get into the bath and just wipe yourself. It's enough.”

Nzima's love for Lilydale seems inexplicable. Still, it's deep and very real. When the town's residents chanted their demands for water, he chanted with them. He stood on the village's dusty streets for hours waiting for Bushbuckridge mayor Renias Khumalo to explain how his municipality would solve the water crisis. Nzima shared Oros with the tired teenager who sat next to him.

He says he didn’t approve of the community's decision to burn down Lilydale's municipal offices and buildings. But the mild-mannered 78-year-old understands the anger behind the destruction.

“They are quite right. I'm supporting them. They are right to show their anger and to show that it's for quite a long time that they don't have water in the place. Now because they've been demonstrating and all that, the MEC and the mayor came down to solve the problem.”

Nzima attended a meeting between community leaders and Khumalo at the height of the Liliydale riots. Surreptitiously sipping bottled water while he listened to their grievances under a tree, he promised that he was doing all he could to solve the crisis. More tankers would bring water to Lilydale he said, while the municipality tried to replace the stolen transformers that had once ensured that Lilydale's borehole water was safe.

Khumalo, however, knows his office is incapable of solving the area's water problems.

His municipality is already R228-million in debt to the water board, and its previous inability to pay off the debt has seen the area's water cut off for days. The department of water affairs attempted to solve Bushbuckridge's water woes in 2005 by spending R175-million on pipes intended to join the Injaka Dam to surrounding villages. But the pipes were plastic and they burst almost as soon as they were opened.

Khumalo says he has begged the Mpumalanga government and the water affairs ministry for help. They have now formed a task team that he believes will “help address this issue”. But he can't say when that will happen because, he says “there are many factors at play”.

The opaque clichés don't give any indication of just how the suffering of Lilydale's people will end.

As the water crisis in Lilydale intensifies, the area's local clinic has recorded a spike in reported cases of bilharzia, a waterborne disease that can, if untreated, lead to renal failure.

According to Lilydale matron Eslina Mahanuke, most of those infected are young boys.

“They are using the water from the springs and the water from the rivers, some of which aren't moving. But there's also sewage in those rivers, it gets washed there by the rain.

“I want to ask the government to give us clean water, because it's a right and because this water now is making people sick. Mothers are bringing their babies to the clinic and they are dirty because their mothers can't wash them,” she says.

"I am scared, yes, I am scared that cholera will come to this place and people will get very sick. I'm scared that we can't stop that.”

Nzima is all too aware of the heavy price the water crisis is already claiming.

“There is bilharzia. This is a place where children are suffering a lot from that because of the water that is not purified.”

Again, I ask him why he stays.

“I was born and brought up among the community so to live with them I feel very much comfortable in this community because I'm used to solving people's problems, so I'm happy to help them to solve this water problem. Whatever they do, I'm always with them.

I lived a long time in the city of Johannesburg, but I feel here now I'm free. Although I was under house arrest in this house, I feel free to live in this house again.”

As we leave, he asks me if he can show me “something beautiful”. He lifts a tarpaulin cover off a large object kept under a tent in his yard. The moon illuminates gleaming stone curves and then I see it: a sculpture of Hector Pieterson.

“I want to start a photojournalism school in Lilydale... I want to put this up at the school,” he says.

“People must know that that this place is special. They must know that things can change. Even when you are crying, things can change.” DM

Photo: Sam Nzima. DAILY MAVERICK/Karyn Maughan.