For years, author Heidi Holland has lived a life reflecting on the people and events around her in Southern African liberation movements, as well as her own reactions to these events as they unfolded.

Over the years, too, she has written prolifically about all of these in her many contributions to the UK's Sunday Times and in many other periodicals, as well as between the covers of insightful, popular books like Dinner with Mugabe and African Magic.

Along the way, too, Holland has come to be the operator of a bed and breakfast spot in Johannesburg that is a frequent gathering spot for foreign journalists, historians and others interested in the shifting circumstances of a changing, kaleidoscopic Southern African political environment.

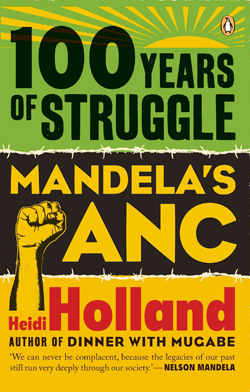

Her newest book, 100 Years of Struggle – Mandela's ANC, comes along just as what is usually called Africa's oldest liberation movement celebrates its centenary. Holland's book joins a growing roster of histories, biographies and other volumes tackling the nature of South Africa's political transition and the outsized impact of its most famous leader, Nelson Mandela.

It is also a year that is replete with considerable controversy, some of it self-inflicted, on the part of the ANC. As the almost daily headlines in the media – not least of all in Daily Maverick – continue to chronicle it, the political mothership continues its struggle to regain control of its increasingly dysfunctional offspring, the ANC Young League.

It also struggles to stifle a still-not-quite-public competition to replace its current head and national president, Jacob Zuma; to contend with awkward, still-unresolved relationships with big business and some feisty, independent media organisations; to wrestle successfully with the internal rot of careerism and insider corruption; and to resolve how to make the move, finally, from a secretive revolutionary movement to a normal – albeit dominant political party in an increasingly non-revolutionary state.??All of this comes as the party's control over the mechanisms of national government must also somehow address growing national challenges in education, unemployment, lack of job creation and international economic competitiveness. Then there are still the boring but crucial quotidian tasks of government: water, lights, sewage, transportation and everything else now lumped together under the supposedly anodyne, technocratic phrase: service delivery.

Any similar litany of tasks and challenges would be a serious, compelling – even life threatening – shopping list for any political movement in any nation. Over the years, political parties and movements around the world have first foundered, then been split asunder or disappeared entirely when faced with internal challenges similar to those of the ANC in South Africa.

Rather than merely enumerate and quantify such challenges, Holland's book attempts to set out the historical landscape and processes that help explain why the ANC has managed to avoid, so far, such an existential moment. As a result, this may just mean that while the party's current travails are serious and important, they are not life-threatening – that deep within this movement, besides these well-known fissiparous tendencies, there is a sufficient reservoir of energy and strength to generate a redemptive quality too.

And so, rather than just a simple, straightforward history or an unabashed memoir, this volume is actually two conjoined halves – or, more precisely, a final third and then the first two-thirds with a bit of a narrative bridge thrown in as well.

For the first portion, Holland is a careful, even sombre chronicler of the slow evolution of the ANC from an elitist, refined gentlemen's debating club to its evolution into a much broader church of an organisation prepared to launch mass protests, public appeals to national and international audiences, and an underground armed wing.

The book’s bridge portion carries the saga through the upheavals of 1976 and their immediate aftermath, in which the ANC was initially something of a marginal player. Holland then moves on to a story that explores the ANC's transition to power, Nelson Mandela's gaining control over the state, and then Mandela's gradual hand-off to his successors to face – or avoid – the many unresolved problems confronting the country, government and party.

By this section, Holland's voice shifts. She is a much more personal and immediate presence herself in the narrative. This is not particularly surprising, given her close position as an intimate observer of these events, and the people who shaped them.

In conversation, Holland reminds us that an earlier version of this book had only carried the story as far forward as 1989. At that time she had been shuttling between Lusaka and Johannesburg for the creation of first version for interviews and research with the ANC and its leaders, even while it was still a banned body.

Holland explains that in this newly expanded, thoroughly revised book, she has focused less fully on the grand forces of history and the movement's theoretical positions, and more on the personalities and personal values of the ANC's leaders over the years.

There is a bit of an irony here. Generations of ANC party leaders – most of all Nelson Mandela – have usually argued publicly that their positions were the party's positions. They were dedicated, disciplined members and did – and do – not hold individual views.

If Wordsworth could write that the child was the father of the man, the disciplined cadre could insist that the party was father of its men, even as it becomes clear from Holland's book that there has been a fair bit of adolescent rebellion against that childhood “father” over the years.

The earlier parts of the book, given their exploration and examination of a political movement in opposition but also in exile, offer the kinds of insights that come to a keen-eyed and attentive observer who is very close to the events described. In exile, the ANC opened up to Holland in a way that was almost unique for outsiders. Regardless, Holland offers sympathetic but even-handed views. She is no apologist or propagandist for its centralised decision-making and clearly less than democratic principles in operation while in exile.??Holland didn't start out as an intimate of the ANC or its leadership. Born into a South African/Swiss, then Rhodesian, family, her father's attitudes towards race were entirely typical of his times. But she moved sharply leftward during her formative educational years and early working life, which included years as a correspondent for the Sunday Times in Rhodesia/Zimbabwe and in South Africa.

Shortly after her book’s release, Holland explains that her social conscience first evolved from early experiences such as when her father took her to the local farm labourers' compound to give her a sense of the dangerous fragility of Western values and social order in Africa, a kind of “there but the grace of God go thee” that actually provoked an awakening instead.

Holland worked in a bank, was a political organiser for an opponent of Ian Smith and, as a journalist, edited Illustrated Life Zimbabwe, where she famously put a picture of Robert Mugabe on the cover, just as the Zanu leader was let out of jail. She began the project that became her newest book back in 1986. She had wanted to write a book about Nelson Mandela, but the research was hard to do in South Africa and getting access to many records in university libraries was a mission.

Holland notes that when she began this effort, Mandela was not really a household name anymore and that few people even knew what he looked like because the mere publication of a photograph of him was banned. This led to trips back and forth to Zambia to ferret out more information. In this way the book evolved into a broader history of a movement, rather than a biography of one man, even if that one man loomed increasingly large in that history.

Once again she had the luck of especially good timing. The resulting volume, The Struggle: a History of the African National Congress, just happened to go on sale the week Mandela was released. When she met him to present a copy of her book to him, she says that he looked at her, bemused at the extraordinary timing, saying to her, “How did you manage to write this book?”

This time around, the book coincides with the all-pervasive centennial year and carries the documentation through to the present as well as including more autobiographical detail on herself. Asked to explain the difference in texture between the two volumes, she says this new one is a warmer volume, with an epilogue that speaks about the former president as a man, rather than a mere abstract set of ideas.

Conversation turns to the historical circumstances of the United Democratic Front's role in South Africa in the 1980s and early 90s and the kind of leadership it had, and produced. Holland observes that the UDF was a truly remarkable body that really did grow from the grass roots, amidst obviously fertile ground for such development that included the fall of the Berlin Wall and the growing impact of economic sanctions. The rift between 'inziles' and exiles came with the return from Zambia and beyond.

We speak more broadly about the question of leadership in South Africa. Tracing backwards to answer the question of the many influences on leadership is a question becoming increasingly important to historians as they shift through the impact of the Communist Party on the ANC, as well as less obvious tendrils such as those emanating from the ideas of the New Unity Movement, the effects of missionary education and the significance of the Christian elites as communities of influence.

This, in turn, takes us to a contemplation of the curiosity of how current leaders can manage to be simultaneously both self-declared communists and staunch church- goers. Holland reminds me that her book African Magic addressed a very similar question of how people in this country can manage to hold – and balance – diametrically antithetical world views such as the importance of the mystical and that of Christianity for sangomas and their adherents.

Asked about whether she is now disappointed about how things have turned out, given the bright, early promise of liberation, Holland considers this carefully and offers a slow, nuanced: “Well yes, but it could have come out so much worse after all.”

We are now entering territory where there are few easy answers. She reminds me that the ANC came back to South Africa as a liberation movement, rather than a body poised for the realities of government. It is on record that the ANC economic policy people were astounded, mouths agape virtually, when they received their first real briefings on the state of the economy and government finance from the then-leadership, at the cusp of the transfer of power.

For Holland, the cruellest challenge now is that would-be officials and bureaucrats are forced to fall back on the invisible but real lines of patronage and loyalty to secure their futures. Perhaps it was inevitable, she says, but this has real repercussions and effects too. I interject that this is the old Chicago mayor Richard Daley style of things, but the corollary was that one also had to be able to deliver. It is not quite as clear here, now.

As to the composition of the governing party and its allies, Holland notes that there is a tension between the party and the judiciary and the media, and this stands in opposition to the way both institutions came to be tacit allies of the liberation movements, especially in the final stages of the apartheid regime. This is a tension, therefore, that is unresolved, and is especially complicated by the fact that these two are effectively the only real opposition balances to government in the current situation.

Our conversation circles back to the influence of the one indispensable man, now that he is in his final years. Holland notes, “It was always ridiculous that one man would absolve us of this appalling history of ours.”??And of the growing influence and impact of political, governmental corruption, Holland adds that, in retrospect it seems almost inevitable now. Returning exiles and others have those large families and so little to fall back on to assist others in getting along and moving up.

In exile, the party did its weekly distribution of foodstuffs and a tiny per diem payment. There were payments from abroad to carry along the party and there are darker rumblings of how illegal activities helped with funding. During much of its exile years, the party was effectively on autopilot, with a great moral compass on the big issues but relatively less effectively so in the smaller, quotidian universe.

Still, given what the nation has been through, there remain reasons to be optimistic. All things considered, race relations aren't so much of a problem as opposed to what might have been. Looking forward, though, like so many others, Holland says she has a slight sense of dread at the thought that Nelson Mandela will pass away soon enough.

When all is said and done, “he represents everything we would like it to be.” For her, the next generation of leadership looks rather more like a question mark. What do they stand for, really? Now is the time for the watching and waiting. Meanwhile, the task for historians, chroniclers and others is to explain “who we really are” as a complicated, tangled society and nation. DM

100 Years of Struggle – Mandela's ANC, Heidi Holland, Penguin Books, 2012, ISBN 978-0-143-52879-1

For more, read:

- Dinner with Mugabe (interviews and articles by Holland).

- "Within me, there is a charitable disposition towards others". Extracts from a rare interview with the controversial president of Zimbabwe, Robert Mugabe.

- African Magic: Traditional Ideas That Heal A Continent .

Photo: Portraits of current and former African National Congress presidents, (bottom L to R) Pixley Seme, James Moroka, Albert Luthuli, Oliver Tambo and Nelson Mandela, (top L to R) Thabo Mbeki and current president Jacob Zuma are seen at the entrance of the Luthuli house, headquarters of the ANC in Johannesburg, 3 April 2012. South Africa's ruling ANC party on Tuesday harshly reprimanded rebellious Youth League leader Julius Malema, angrily condemning his assertion that President Jacob Zuma's government is a dictatorship. REUTERS/Siphiwe Sibeko.