I met for lunch the other day with one of South Africa’s most knowledgeable commentators and no, this time not iMaverick’s own Stephen Grootes to talk about South Africa’s foreign relations. Expressing mystification, this thoughtful man turned to ask what, in our opinion, was the primary trajectory of South Africa’s foreign policy and how one could define it? Say what you will, he said, under Thabo Mbeki one might not like the direction of policy, but at least one could understand and predict it. Unfortunately, President Zuma’s recent speech on South Africa’s foreign policy has not clarified things enough for many observers.

Following our lunch, it occurred to this writer that South Africa’s foreign policy echoes the parable of the fox and the hedgehog Isaiah Berlin had drawn out from a brief snippet of classical Greek poetry: “The fox knows many little things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing”. Berlin took this striking image to differentiate between those who see the world in one overarching idea (avoid becoming lunch for some other creature) versus those who see a whole range of choices, crises, challenges and opportunities.

Under apartheid, South Africa had the hedgehog’s monomaniacal world view: the crucial thing was to stave off its creeping international de-legitimisation or destruction by maintaining trade ties whenever and wherever possible, and building its military power to keep the state’s enemies in line or at bay. Coincidentally, the liberation movement also saw the world through the eyes of a mirror-image hedgehog. Their task was to encourage the de-legitimisation of the apartheid state by any means necessary.

Post-1994, South Africa’s changed international circumstances prompted the now-internationally accepted state to see the world through the gaze of the fox – even as the hedgehog’s view lingered as a palimpsest of moral direction. Only a few months ago, South Africa’s Minister of International Relations and Cooperation, Maite Nkoana-Mashabane, had tried to reconcile everything in telling an audience at the SA Institute of International Affairs that: “South Africa’s foreign policy is by its orientation a campaign for a humane and equitable world order. Our history is a living testimony of what we gained from and will contribute to a culture of human solidarity across the globe.”

However, that emphasis on a humane world order has proved harder to achieve in practice than pronouncement. Consider Nelson Mandela’s unsuccessful effort a decade-and-a-half ago to prevent Nigerian ruler Sani Abacha from executing author-activist Ken Saro-Wiwa and other human-rights activists. The resulting failure demonstrated how difficult it was to lead solely by moral virtue.

Moreover, for more than a decade, South African orientation towards Zimbabwe has been torn between “real politick” and Nkoana-Mashabane’s statement of South Africa’s first principle. Proximity, rather than a reliance on principle, seems to dictate its polices towards Swaziland as well.

South Africa has also expended great diplomatic energy in insisting on a kind of cautious institutional “proceduralness” in its international dealings with Burma and North Korea, rather than elevating concerns about those states’ domestic authoritarianism much more in line with Nkoana-Mashabane’s statement of first principles. And, until its support for UN Resolution 1973, establishing a no-fly zone over Libya, South African relations with that nation had appeared to be built more on historical Libyan support for South African liberation movement and its financial backing of the AU than on anything else.

South Africa has directed much of its foreign policy architecture and spent much energy on the procedural elements of participation in formal diplomatic structures, and less in aiming for real outcomes and then finding the mechanisms that are best suited for achieving these goals, as in its role within SADC, the AU, at the UN Security Council and now, most recently, within the Brics grouping.

By contrast, many middle-income, mid-level nations comparable to South Africa have bent their diplomatic energies towards improving their economic circumstances through a full court press of export promotion, robust partnership with their business sectors and vigorous efforts to capture foreign investment and trade to move up the international economic value chain.

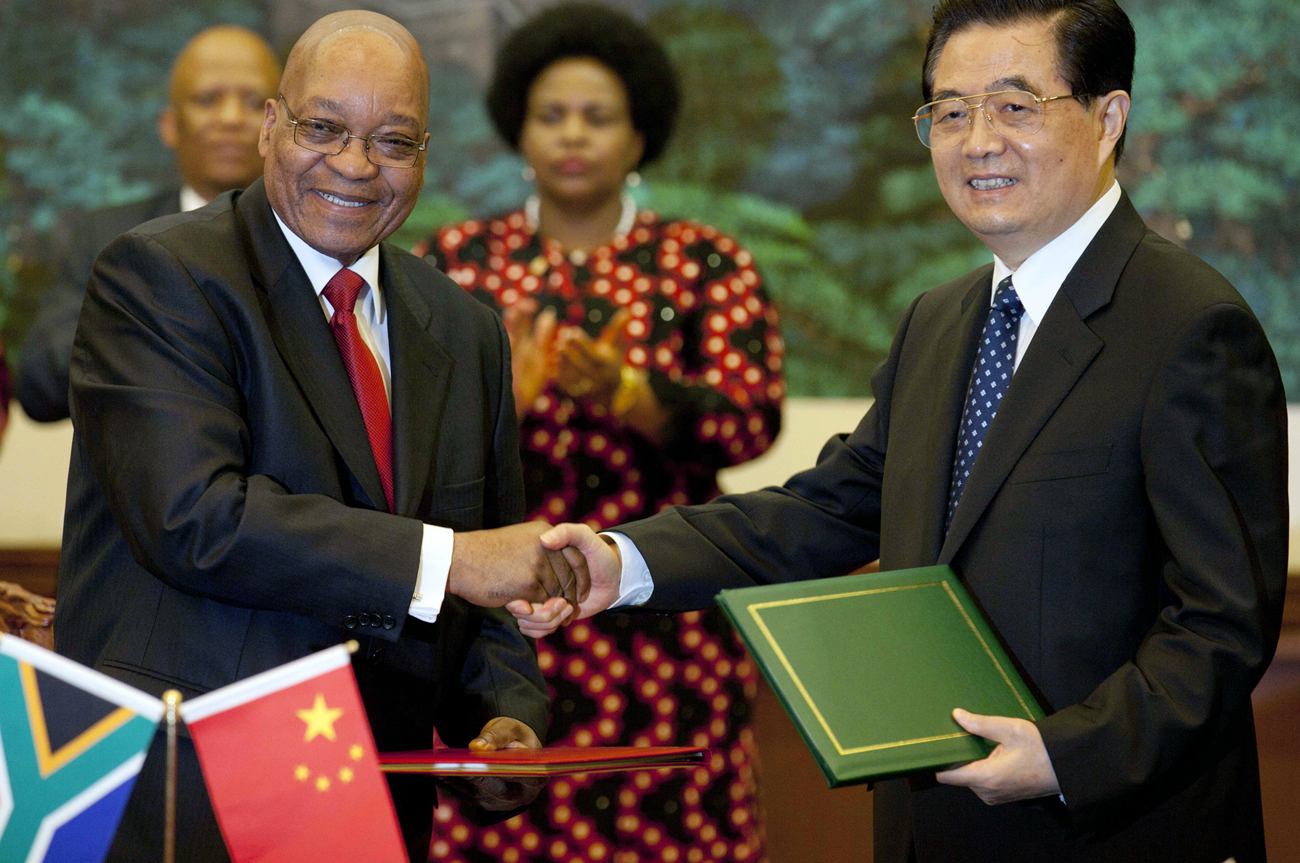

South Africa’s foreign-policy leaders sometimes seem wary of a too-intimate embrace of the national business sector, perhaps sensing in such relationships a betrayal of older liberation principles. But even here, there is a deep inconsistency. South Africa has easily embraced the growing Chinese economic presence in Africa, seeing China as a counterweight to American and western influence, and as its newest and best natural partner. The recent debacle over the Dalai Lama’s putative visit has only heightened this view – as well as a belief that where China is concerned, the presumed intentions and benefits of Chinese investment trumps everything else. Or as international affairs scholar Peter Vale argued in a recent newspaper column:

“As we have recently learnt from the fiasco – we should say, second fiasco – over the Dalai Lama’s visa, many believe that two successive South African governments – Thabo Mbeki’s and now Jacob Zuma’s – have betrayed the high hopes of the human rights community not only at home, but abroad, too… It seems clear that in the aftermath of apartheid isolation – and we tend to forget how lonely we felt – and the drama of our own transition, we, too, believed that we had a responsibility to free peoples everywhere… The problem for policy-makers was this: how to turn exceptionalism into coherent policy in a world in which economics was everything.”

Finally, South Africa seems to be reluctant to embrace the international prominence of the country’s media and its arts and culture sector. Too often, important and independent South African cultural figures and institutions struggle to gain sufficient backing for an effective international presence – in lieu of more pedestrian efforts by state-selected flag-wavers. Paradoxically, in the worst days of apartheid, the liberation movements and their supporters were adroit in using cultural figures and the cultural, academic and sports boycotts to draw attention to South Africa’s circumstances and to generate increasingly stern international opposition to the government.

The difficulty in explaining the country’s international policies clearly, President Zuma’s recent speech became enmeshed in the same difficulties. In his speech, Zuma had said:

“The basis of our foreign policy was crafted by ordinary people of the Republic of South Africa, and is embodied in the Freedom Charter of 1955. The Freedom Charter proclaims that there shall be peace and friendship, and outlines the following aspects of foreign policy:

‘South Africa shall be a fully independent state which respects the rights and sovereignty of all nations; South Africa shall strive to maintain world peace and the settlement of all international disputes by negotiation - not war; Peace and friendship amongst all our people shall be secured by upholding the equal rights, opportunities and status of all; [and] The right of all peoples of Africa to independence and self-government shall be recognised, and shall be the basis of close cooperation’.”

And he went on to elaborate that: “…Our foreign policy is an extension of our domestic policy and our value system. As South Africans we believe in a democratic and open society in which government is based on the will of the people and every citizen is equally protected by law. We believe in a society based on democratic values, social justice and fundamental human rights. To implement this vision, the country's Foreign Policy is based on four central pillars.

“We accord priority to SADC and Africa as a whole. We work with countries of the developing South to address shared challenges of underdevelopment. We promote global equity and social justice. We work with countries of the developed North to develop a true and effective partnership for a better world. And finally, we play our part to strengthen and transform the multilateral system, to reflect the diversity of our nations, and ensure its centrality in global governance.”

And just the other day, the South African government underscored its commitment to such core values at the recent India-Brazil-South Africa summit, agreeing: “…The [three] Leaders highlighted that the basic pillar of IBSA is the shared vision of the three countries that democracy and development are mutually reinforcing and key to sustainable peace and stability. The Leaders posited that the entrenched democratic values shared by the three countries to the good of their peoples and are willing to share, if requested, the democratic and inclusive development model of their societies with countries in transition to democracy.”

While the earnest sentiments for Nkoana-Mashabane’s first principle are there yet again – and reach back to the moral basis of the liberation movements – the president’s speech soon becomes a laundry list of agreements signed and meetings attended.

Leading the charge in response, columnist Justice Malala judged the president harshly, writing “Zuma is the laughing stock in his own party in terms of policy issues. Even ANC die-hards wonder openly whether he has a clue about South Africa's foreign policy except to call Beijing for directions on which line to take.” Even if one does not go quite that far, it still seems fair to say that in speaking to the challenges confronting the country, the president stepped aside from exploring how South Africa will embrace the difficult challenges of balancing its fundamental interests – those moral, economic, political, social and intellectual ones – with its deepest, dearest principles, and what kind of policies that will mean in dealing with the realities of today’s world. DM

Read more:

- The Hedgehog and the Fox: An Essay on Tolstoy's View of History;

- President Zuma on “Aspects of South African Foreign Policy” at the University of Pretoria, full text;

- Can Suu Kyi shield others from what she suffered?, Peter Vale in the Daily Dispatch;

- South Africa’s foreign policy objectives: Reviewing the White Paper, on the SAIIA website; and

- 'Flip-flop Zuma' is a fish in troubled water, Justice Malala in the Sunday Times.