In many homes where there is a copy of the Bible, it is likely the version popularly called the King James Bible. The writer’s own bookshelves have several editions of that particular translation, along with a couple of scholarly concordances to help us understand what those old-time, Shakespearean cadences are telling us.

Unless you happen to be of the persuasion that asserts this collection of stories, histories, poems, narratives and religious admonitions were all dictated directly to mortals by a divine presence, this collection is a repository of writings, from many sources and authors, from over a thousand or so years of history. Some clearly drew from earlier traditions such as the Mesopotamian Gilgamesh story for the Noah saga, or the fact that several different, earlier textual origins have been identified by scholars on the basis of linguistic analysis for the first five books of the Bible.

By late Hellenistic times, what is generally called the Old Testament had essentially been codified in Hebrew (although variant versions of some texts were well-known, well into late Roman times). To assist the city’s large Jewish community there who were fluent in Greek, but not in the languages of their forefathers, scholars living in Alexandria completed a major translation project, the Septuagint (the seventy) by 132 BC – the first sustained translation Biblical project.

As the Talmud – the ancient Jewish commentary on religious law and custom – described this project: “King Ptolemy once gathered 72 Elders. He placed them in 72 chambers, each of them in a separate one, without revealing to them why they were summoned. He entered each one's room and said: ‘Write for me the Torah of Moshe, your teacher.’ God put it in the heart of each one to translate identically as all the others did.” Regardless of whether or not it happened quite that way, the Septuagint clearly set a pretty high bar for future Biblical texts translated by a committee – such as the one assembled by a British monarch nearly two thousand years later.

By that time, the demand in England (and Europe more generally) was growing for access to the Bible in the vernacular – as opposed to Latin or Greek – despite those who stood against any “cheapening” of the Bible by allowing any literate person to read it without the intervention of a priest.

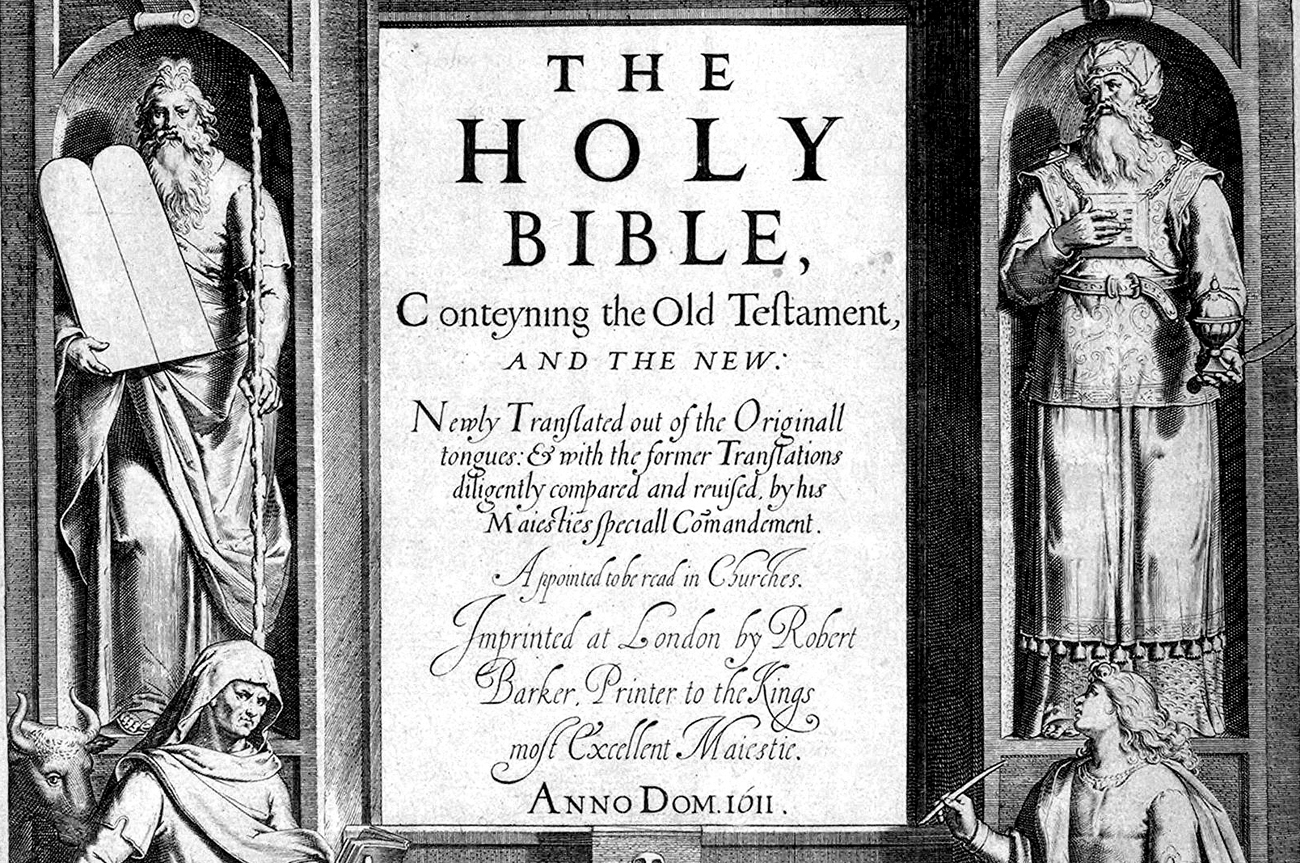

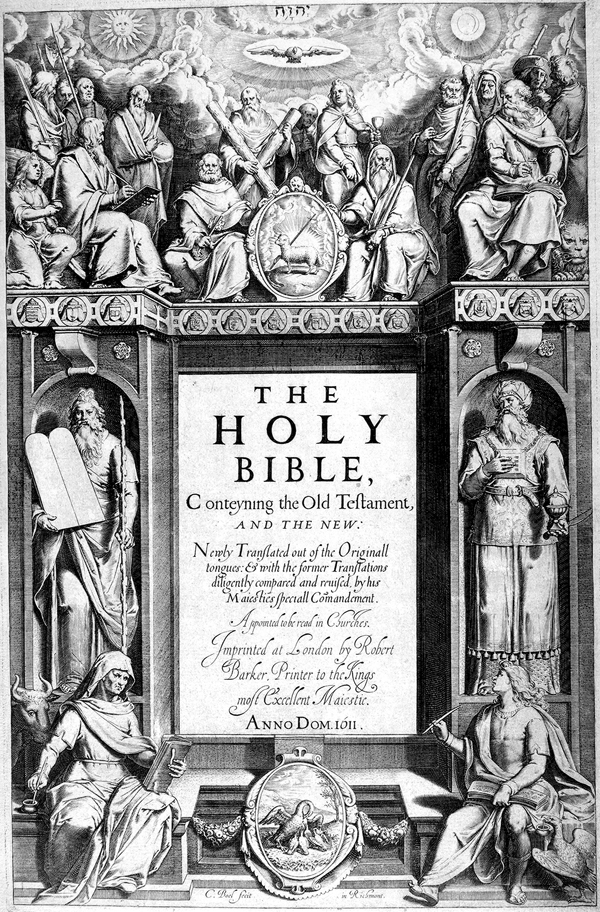

The Authorized Version, now usually called the King James Version, was a major English translation project carried out by the Church of England from 1604 to 1611 in response to perceptions that there were significant errors in earlier translations. In 1525, William Tyndale, an English contemporary of Martin Luther, had carried out the first English translation of the New Testament and started out on a translation of the Old Testament as well. Despite some controversial linguistic decisions, Tyndale's work and prose style became the basis for all subsequent renditions into Early Modern English. Myles Coverdale then adapted Tyndale’s earlier work and the resulting work then became the basis for an “authorized version” issued by the Church of England during Henry VIII’s time.

Besides making a good read, King James’ official instructions to the translations committee had the subliminal purpose of undermining the rise of the Puritans and exalting the episcopal structure of the Church of England and its beliefs about an ordained clergy. The King’s instructions also included a requirement that the translating team use that earlier translation as their fundamental roadmap, and that the translation team take pains to retain the style of familiar biblical proper names so readers could keep track of who was who. In contrast to the Septuagint’s 70 (or 72) ancient linguists, 47 scholars took up the religious cudgels for King James. Within 150 years, this new version had become the unchallenged gold standard biblical translation.

Setting out on their project, the 47 scholars worked in six committees located at Oxford, Cambridge and Westminster. The various groups included high church and puritan sympathisers, and all worked from special unbound copies of the earlier Bishop’s Bible, but printed with extra-wide margins for recording their debates, disagreements and – ultimately – their concurrences. They didn’t get paid for their work, although bishops around England were encouraged to consider the translators for appointments to well-paid church jobs whenever they became vacant – the quality of the resulting work seems to be a pretty clear refutation – at least in this case – of the old maxim that you only get what you pay for!

Among early oddities in the first edition were the so-called “he” and “she” versions. In one, Ruth 3:15 reads “he went into the city”, and the second reads “she went into the city”. Moreover, the original came out before English spelling was standardised. As a result, printers often substituted a v for an initial u and v; and u for u and v everywhere else – confusing four centuries of readers. And when space needed to be saved, these printers sometimes used ye for the – encouraging the linguistic affectations of generations of cutesy sign painters in historic towns in the UK and New England.

Initially, at least, not everyone was a fan of the translation. Hugh Broughton, the most highly regarded English Hebrew scholar of the time, had been excluded from the translation committee. Reading the new work, he wrote “he would rather be torn in pieces by wild horses than that this abominable translation should ever be foisted upon the English people”.

In a period of rapid change in the English language, the translators avoided contemporary idioms, tending instead towards forms that were already slightly archaic, like “verily” and “it came to pass”. In spite of – or perhaps because of – the fact, the King James Bible has been called “the most influential version of the most influential book in the world, in what is now its most influential language” and “the most celebrated book in the English-speaking world”. It contributed some 257 idioms to English, more even than Shakespeare. Unlike virtually any other 400-year-old book, it remains protected under a United Kingdom Crown Copyright inside the UK.

Oh, and if readers have any questions about the Bible more generally, one evangelical website in the US advertises a 24-hour question answering service – readers can call 00-1-877-966/7300 or 00-1-571-295-5121; spiritual advisers are standing by. DM

Read more:

- The King James Bible Online – the entire Bible online;

- The enduring appeal of the King James Bible, 400 years after its original publication from the BBC;

- Septuagint from Wikipedia;

- Bible Facts and Statistics (a website with more Biblical numerology than anyone will ever need);

- Authorized King James Version from Wikipedia;

In concert to many other celebrations, a special commemorative choral event, “Songs of Praise,” in honour of this 400th anniversary, can be heard in Johannesburg on 18 September, at 3pm, at the Linder Auditorium.