Every year about 130 of the world’s most influential global leaders, diplomats, capitalists, economists, intellectuals and media owners meet at a secure luxury location for off-the-record discussions. Called the Bilderberg Meetings among 2010’s “cabal” were Bill Gates, Finland’s minister of finance Jyrki Katainen, Henry Kissinger, Eric Schmidt of Google, Craig Mundie who heads up research and strategy for Microsoft and The World Bank’s Robert Zoellick.

Over the years Bilderbergers have included the likes of Bill Clinton, Prince Charles, Colin Powell, Queen Beatrix, Gordon Brown, Tony Blair and Margaret Thatcher. Bilderberg founder Denis Healy tells a great story about Thatcher’s first appearance at the exclusive group in the mid-1970s before she became a world politician.

Thatcher sat through her first gathering without uttering a word. After complaints about her silence – this was, after all, an elite gathering of talking heads – Healy appealed to the “iron lady” and the next day she addressed the gathering for three minutes in true Thatcher style. “As a result of that speech, David Rockefeller and Henry Kissinger and the other Americans fell in love with her,” says Healy. “They brought her over to America, took her around in limousines and introduced her to everyone.” Four years later Thatcher was elected prime minister of the UK. Obviously Thatcher led a great campaign that won her election, but clearly the Bilderberg connections didn’t hurt her.

The Bilderberg Meetings fuel as much interest from conspiracy theorists as the death of JFK or the hypothesis that the world is controlled by reptiles that shape shift. But what’s certain is that the changing list of participants invited over the years shows a shift in the type of influential elites invited to attend. This change supports Robert Guest’s theory that the global elite is becoming more meritocratic.

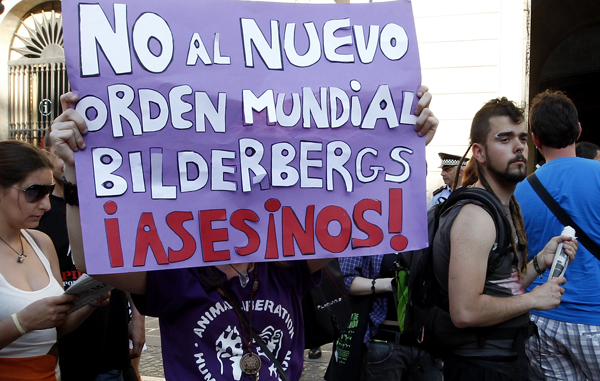

Photo: People protest against the Bilderberg meeting in central Barcelona June 5, 2010. The Bilderberg Group is an unofficial conference of around 130 invitation-only guests who are insiders in politics, banking, business, military and the media. The group's meetings are held in secret and are closed to the public. The placard reads "Not the new world order, Bilderberg murderers" REUTERS/Gustau Nacarino

Business editor for The Economist, Guest says that during the past century the biggest change in the world’s elite is a move toward meritocracy. “The richest people in advanced countries are not aristocrats, but entrepreneurs like Bill Gates,” says Guest, who adds that the most influential are those whose inventions, like Facebook, change lives or people whose ideas are the most persuasive.

“There’s this notion that corporations are more powerful than governments, which is rubbish. They can only maintain their position by constantly improving on what they are selling. In a democracy people have the opportunity to change governments every four years or so. At Walmart millions of people are voting for the retailer literally every minute. This shift in power is huge and isn’t widely understood. There are, of course, exceptions to this, particularly in the financial arena, where banks have been supported by the state. But governments should stop this because competition cedes power to consumers. Some banker’s fortunes are made at taxpayers’ expense, but in most industries consumers call the shots and competition forces companies to do their bidding.

“The big question is, does the global elite serve the masses? To a large extent it does,” says Guest. “The power of a lot of the most important people in the democratic countries depends on them pleasing a lot of ordinary people. As soon as they stop pleasing people in mature democracies, they get thrown out of power. In the old days great fortunes were often inherited, but these days just about everybody on the Forbes list is self-made. And entrepreneurs generally make money by providing good services at prices that people want to pay.”

When the Forbes Richest List first started close on 100 years ago it was well populated by names of American families renowned for their wealth, like Rockefeller and Vanderbilt. Today the world’s richest man is Carlos Slim Helú, a Mexican telecommunications magnate whose business interests are said to be worth about $74 billion. That’s $18 billion more than Bill Gates and $24 billion more than Warren Buffett, the world’s second and third richest men.

Slim was taught business by his father who was an immigrant trader. By the age of 12 he had bought his first shares in a Mexican bank. Fifty-five years later The Wall Street Journal ran a cover story on him saying he was possibly richer than Bill Gates. By March 2007 Slim had eclipsed Warren Buffet. A couple of months later he really was richer than Gates.

Slim might be the richest man in the world, but is he influential and does lucre readily translate into clout that counts? Guest says Slim’s fortunes were largely built off the back of government connections and that cash seldom buys political power, but can purchase a megaphone. “America is often caricatured as a country where the government is up for sale. Rich candidates can buy airtime and can occasionally win power, but very often this flops as evidenced by the examples of Ross Perot, Mitt Romney and Steve Forbes.”

Watch Robert Guest talking about the global elite on YouTube:

type="application/x-shockwave-flash">