The biggest, most far-reaching impacts of this massive data dump may not be on the broader outlines of “national security”, or even the specifics of American military tactics and strategy in Afghanistan. Rather, Obama and his Democratic Party’s political prospects in America’s upcoming mid-term elections in November, the country’s always-prickly relations with Pakistan, the commitment of many Afghans to cooperate with Americans in the future and US relations with key allies and cooperating nations are all likely to be the real collateral damage of Julian Assange’s handiwork.

Ultimately, too, this tidal wave of data - and likely similar ones in the future - will mean real changes in how every government worldwide will handle confidential information once the larger lessons of Wikileaks are absorbed. If the Internet was “the death of distance”, the Wikileaks era may become secrecy’s graveyard too.

Some officials in the US are still in a kind of collective shock, calling Wikileaks an unprecedented breach of national security and a violation of the way Americans treat military secrets. But there has always been tension between those who seek the protection of secrecy in government information and those who argue for sunlight as the great disinfectant to preserve the greater public good.

Half a century before America’s Declaration of Independence, publisher John Peter Zenger was accused of printing unflattering information about New York’s colonial governor. Eventually acquitted, Zenger would write: “No nation, ancient or modern, ever lost the liberty of speaking freely, writing, or publishing their sentiments, but forthwith lost their liberty in general and became slaves.”

The media’s weakest moment probably came in the spring of 1961. The New York Times reporters had discovered the CIA was planning an invasion of Cuba to topple Fidel Castro, using an army of Cuban émigrés and disguised military-style aircraft. Fearing disclosure would lead to failure of the invasion, president Kennedy called Times’ editor-in-chief and successfully convinced him to pull the story.

The invasion collapsed quickly, but it convinced Soviet premier Nikita Khrushev to station nuclear-tipped missiles in Cuba, and that act nearly led to a nuclear clash between the superpowers in the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. And, of course, the Times’ editor said it would be the last time he ever spiked a story because of a presidential phone call or a White House threat.

Now, fast-forward a decade to Vietnam. With the US bogged down in the war, the Pentagon commissioned a classified, 47-volume study of its own war in Southeast Asia to figure out how the US had gotten stuck there. Daniel Ellsberg, a disillusioned, former defence department economist, gained access to the work and photocopied much of it page-by-page so he could give it to the media. As The New York Times began publishing the materials, the Nixon administration went to court to get an injunction to stop it . The government was initially successful in getting a restraining order to prevent publication, naturally on national security grounds, but the media appealed to the Supreme Court for redress.

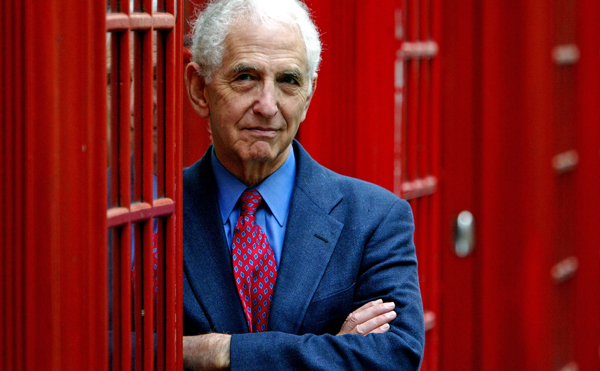

Photo: Former Pentagon employee Daniel Ellsberg poses for photographs in central London, November 1, 2004. Ellsberg, who risked career suicide and a century in prison to blow the whistle on U.S. President Nixon's Vietnam war plans, was visiting Britain to encourage keepers of British government secrets to join his Truth-Telling Project. REUTERS/Stephen Hird

Ellsberg argued he wanted to alert the public to government double-dealing and lying, and the people had a basic right to know what their government was doing (words now familiar from Wikileaks founder Assange’s rationale for publishing the Afghanistan documents). Within two weeks, the Supreme Court had ruled that an effort at prior restraint could not be justified, except in the most extreme circumstances of national security. Or as two of the justices set the bar by arguing, they “cannot say the disclosure of any of them [the documents in question] will surely result in direct, immediate, and irreparable damage to our nation or its people.” Even in war secret materials, even potentially embarrassing material cannot be suppressed, setting the outlines for the current struggle over Wikileaks’ release of its haul of digital secrets.

The Obama administration says it is working hard to find the person - or persons - who gave all this material to Wikileaks, but they may not succeed. There are just too many people with access to this information. The Wikileaks collection comprises data that ranges from evaluations by skilled specialists to quick, abbreviated battlefield communications from patrols back to a local headquarters. Many are in the most obscure possible “military-speak” shorthand.

Regardless, the Pentagon has called the release a “criminal act” and defence spokesman Colonel Dave Lapan said officials were reviewing the documents to determine “whether they reveal sources and methods” that might endanger US and coalition personnel. Making lemonade out of these lemons, however, White House spokesman Robert Gibbs said the digital dump did not divulge anything new about the nature of the war in Afghanistan, even if the details have the “potential to be very harmful to those that are in our military, those that are co-operating with our military and those that are working to keep us safe”.

It is possible there's no one reservoir where all this material could have derived from in the first place. And, as readers have learned from The Washington Post’s recent investigative series, “Top Secret America,” close to a million US government employees or contractors have top-secret clearances, with many of these people holding still more restricted clearances for cryptographic material or what is called sensitive, compartmentalised top-secret information. Just checking up on the activities of all these people, or asking each of them what they were doing on Tuesday, the third week of June, at 3pm, with their computers and hard drives, and then collating the resulting answers, would become a monumental, and possibly self-defeating task. The senders of this info almost certainly know how to cover their cyber-tracks pretty effectively.

Where’s the harm? In fact, some analysts have already argued that there is little in the released documentation that provides new insights into the dynamics of the war, and, in any case, the information comes from the Bush administration of a very different version of the Afghan war. Obama has made the argument that the revelations have further justified his administration’s new tactics and plan to pursue this war.

Watch: Julian Assange on why Wikileaks is important.

type="application/x-shockwave-flash">