Born exactly 200 years ago, on 1 March 1810, Frédéric Chopin was the half-French symbol of Polish nationalism; a co-creator of the new idiom of musical nationalism while he himself lived as a wandering expatriate through most of his life; he was the musical revolutionary who ironically willed that a work written some 60 years before his death, Mozart's “Requiem”, be performed at his funeral.

Passing away from tuberculosis at just 39, he had achieved a prolific creative life, composing nearly 200 piano works including two concertos, sonatas, scherzos, and almost 200 other preludes, etudes, nocturnes, waltzes, polonaises, mazurkas and ballades. All this in addition to a busy life as an eagerly sought-after music teacher to the rich, famous – and, sometimes, talented.

His musical legacy led his contemporaries to describe his music as works of “exquisite delicacy and liquid mellowness” that had “pearly articulation”. But Chopin's name is also almost inevitably linked with his long-time romantic partner, the pants-wearing, cigar-smoking George Sand (Amandine Aurore Lucille Dupin, the Baroness Dudevant), with whom he lived for nearly a decade. Sand and Chopin's most lurid portrait appears in Ken Russell's 1975 cult film, “Lisztomania,” with Sand portrayed as a terrifying dominatrix and Chopin her submissive partner.

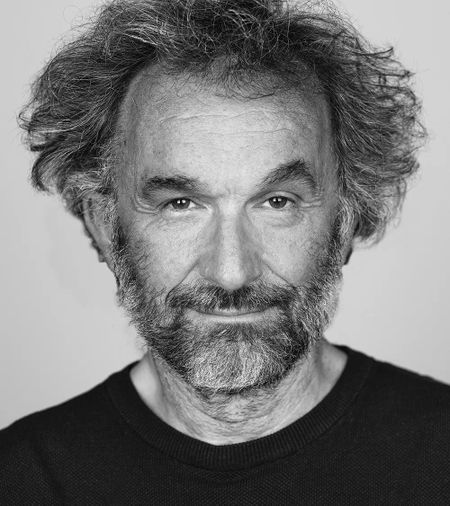

Picture: Chopin's lifelong partner, George Sand.

Like his close contemporaries, Liszt, Schumann, Berlioz, Paganini, Mendelssohn and Schubert, Chopin helped create the stereotype – often accurate – of musicians and composers wedded to romantic ideals that linked music with literature and painting and an urge to express the emotions of love, happiness, sorrow and frustrated passion – as well as the untamed beauty of the natural world. Like his contemporaries too, Chopin was the embodiment of that other hallmark of romanticism in music – the musician fighting a lonely battle against incomprehension and intolerance. Chopin was right on the 19th century version of the bubble, just as the star performer was transforming into a major public figure – even though his music and his concert performances didn't have the Mick Jagger-like impact on 19th century young women that his fellow musician Franz Liszt did. The sensuality of Chopin's music seems to have had a more subtle, sublimated, ethereal influence on women.

WATCH: Chopin - Heroic Polonaise Op. 53 - played by Arthur Rubinstein

Chopin was a key figure in the new wave of musicians who perfected this new romantic image. By contrast, a slightly earlier composer such as Beethoven wasn't nearly as fussy about his instrument – he once sawed the legs off his piano so he could put it on the floor to feel the vibrations better when he composed and practiced.

Chopin was different. On an extended vacation with Sand during one winter, he insisted that his prized Pleyel piano be shipped with him from vacation spot to vacation spot around the western Mediterranean so he could continue to compose, from Paris to Majorca and then on to the south of France, creating the temperamental musician model for modern performers like Vladimir Horowitz. Horowitz used to demand that his own pianos go on ahead, to be acclimatised in the upcoming venues of his concert tours, wherever the great man was scheduled to perform.

Chopin was brought up in a Poland, then under Russian rule. At the age of 20 he left Poland for Italy via Austria, to further his musical studies. However, the suppression of Poland's 1830 revolution made him one of the leading expatriates of its “Great Emigration” to western Europe.

As a child, Chopin's home had been a haven of Polish language and culture, despite the fact that his father taught French and directed a lyceum in Warsaw, and, according to his friends, Chopin never quite got the hang of French, despite living in Paris for many years. (That damned subjunctive will get you every time.) And, like so many other expatriates who yearn for a vanished homeland, his lover, George Sand, described Chopin as “more Polish than Poland”.

WATCH: Chopin - Ballade no 1 - played by Vladimir Horowitz

Chopin was responsible for the creation of new musical forms such as the ballade, he recast dance forms such as the mazurka, waltz and polonaise into extended compositional forms, and he gave new emotion and depth to existing musical forms such as the etude, impromptu and prelude. While his work never took on the avowedly programmatic nationalism of later composers like Dvorak, Smetana, Grieg, Glinka or Granados, nonetheless, when he learned that the 1830 Polish uprising had been crushed, he poured "profanities and blasphemies" into his secret journal and his torments about the failed revolution reputedly inspired his Scherzo in B minor, Op 20 and the “Revolutionary Etude”.

Some musicians struggle for years to gain public fame and adulation. Chopin didn't have to wait. Only a few months after arriving Paris, his first public concert garnered critical acclaim with one critic writing in Revue Musical, "Here is a young man who, taking nothing as a model, has found, if not a complete renewal of piano music, then in any case part of what has long been sought in vain, namely, an extravagance of original ideas that are unexampled anywhere..." Even before that concert, his fellow composer Robert Schumann could write of one of Chopin's compositions, "Hats off, gentlemen! A genius."

The man seemed to lead a charmed life – befriending the Rothschild banking family within two years of arriving in Paris gave him all those contacts and benefits that come from having really, really rich friends. At the same time, he fell in with Paris' artistic elite – becoming friends with such daunting figures as Mendelssohn, Heine, Delacroix and Berlioz among others – while he taught the children of the rich and famous, and gave an occasional concert to keep his reputation as a pianist uppermost in the minds of his admirers.

About Chopin's working style, his partner, George Sand, would write:

“Chopin is at the piano, quite oblivious of the fact that anyone is listening. He embarks on a sort of casual improvisation, then stops. 'Go on, go on,' exclaims Delacroix, 'That's not the end!' 'It's not even a beginning. Nothing will come ... nothing but reflections, shadows, shapes that won't stay fixed. I'm trying to find the right colour, but I can't even get the form ...' 'You won't find the one without the other,' says Delacroix, 'and both will come together.' 'What if I find nothing but moonlight?' 'Then you will have found the reflection of a reflection.' The idea seems to please the divine artist. He begins again, without seeming to, so uncertain is the shape. Gradually quiet colours begin to show, corresponding to the suave modulations sounding in our ears. Suddenly the note of blue sings out, and the night is all around us, azure and transparent. Light clouds take on fantastic shapes and fill the sky. They gather about the moon which casts upon them great opalescent discs, and wakes the sleeping colours. We dream of a summer night, and sit there waiting for the song of the nightingale ...”

After Chopin died, but before his funeral took place, in accordance with his dying wish and based on his great fear of being buried alive (he probably read Edgar Allen Poe a little too often), his heart was removed and preserved in brandy. His sister later took it to Warsaw, where it was sealed in a church pillar, below the inscription (Matthew 6:21): "For where your treasure is, there will your heart be also."

The great pianist and Chopin interpreter, Arthur Rubinstein, said of his music:

“Chopin was a genius of universal appeal. His music conquers the most diverse audiences. When the first notes of Chopin sound through the concert hall there is a happy sigh of recognition. All over the world men and women know his music. They love it. They are moved by it. Yet it is not ‘Romantic music’ in the Byronic sense. It does not tell stories or paint pictures. It is expressive and personal, but still a pure art. Even in this abstract atomic age, where emotion is not fashionable, Chopin endures. His music is the universal language of human communication. When I play Chopin I know I speak directly to the hearts of people!”

The first, with many more to follow, concert of Chopin's music in this the 200th anniversary year of his birth, was performed by the brilliant young Chinese pianist, Lang Lang, in Warsaw on 7January.

By J. Brooks Spector

WATCH: Chopin - Etudes - played by Arthur Rubinstein