In heading back to Jozi, the global paper giant will see these costs fast amortised by increasingly efficient trading technologies and contemporary stock market rules that smooth cross-border trade and fit well into the paradigm of globalisation. Sappi CEO Ralph Boettger says it’s now much easier for foreign shareholders to trade directly on the JSE. Anyway, the company is still retaining its NYSE listing.

Apart from listing and publicity costs, the fact that British-based shareholders only have a meagre 0.036% of Sappi’s total issued share capital is another reason it’s coming home. Sappi says the British register will be closed on 2 November 2009, with shareholders on the LSE transferred to the JSE.

This is not the first time Sappi’s got out of European markets. In 2005 it ended its secondary listing on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange after just more than 200,000 shares were traded in 2004, compared to more than 300 million shares on the JSE and some 50 million on the New York main board. Earlier, in 2000, the company delisted from Paris, a spoke in the wheel of liquidity which traded only 35,000 of its 239 million shares at the time.

Additionally Sappi has committed itself to reducing net debt between 25% and 30% over the next three years. This reduces its financing costs, in turn improving its debt maturity profile and strengthening its balance sheet. And now that Sappi is, in fact, a leading global paper company, it says the rationale for its 1992 listing in London – to fund its European expansion - has fallen by the wayside.

Sappi’s move follows Naspers’ decision to delist from the NASDAQ in 2007, based on the high costs of maintaining a listing in the US and complying with the 2002 Sarbanes-Oxley Act. Sarbanes-Oxley dramatically upped the criteria for corporate accounting disclosures following the collapse of US energy-trader Enron and the bankruptcy of WorldCom.

But Sappi and Naspers are not the only South African companies feeling the costs of overseas listings. In June, Telkom announced it was delisting from the NYSE to cut costs after posting a 45.9% drop in full-year headline earnings per share. At the time, one analyst said Telkom needed to reposition itself urgently because the sale of Vodacom cast doubt on the future performance of the company at a time when fixed-line services were losing ground to new technologies. So, in an era of global boom and bust, companies need to be flexible about how and where they operate.

Apartheid drove many away and that may have been rather patriotic of them

When the walls of apartheid came tumbling down, a number of South African conglomerates took off for fresher pastures. Shedding the shackles of international sanctions and the size of the local market, they headed for primary and secondary listings in places such as London and New York. Among the first to leave SA were Anglo American, Billiton, Old Mutual, Liberty, SA Breweries and Gold Fields.

While the ANC and its union allies, predictably, said these companies were looking offshore because they had no confidence in South Africa, the companies were in fact beset by labour inflexibility, over-regulation and government intervention in various industries. More stringent competition policies stymied mergers and acquisitions, and the difficulties of raising capital and foreign exchange controls had left South Africa lagging behind the developed world. So listings abroad suited companies with eyes on globalisation.

Other followed, with Didata and Investec heading offshore. JSE rules are similar to those of the LSE, but London was always an expensive exercise. At one time, some 90% of South African miners were listed in London, but many found it tough to raise capital there. Despite being incredibly costly, executives didn’t wear the right school ties and didn’t belong to the right clubs. So, as it was during the apartheid years, SA companies were viewed with as much suspicion abroad as they were by anti-apartheid activists at home. The myriad opaque cross-holdings on the JSE and the secretiveness among the ranks just didn’t cut it in open markets.

Though Julius Malema and his comrades might applaud Sappi for quitting “imperialist “ markets and returning to more liquid shores -- that’s market liquidity, by the way – it’s departure in the first place probably had less to do with racism and more to do with being “patriotic”.

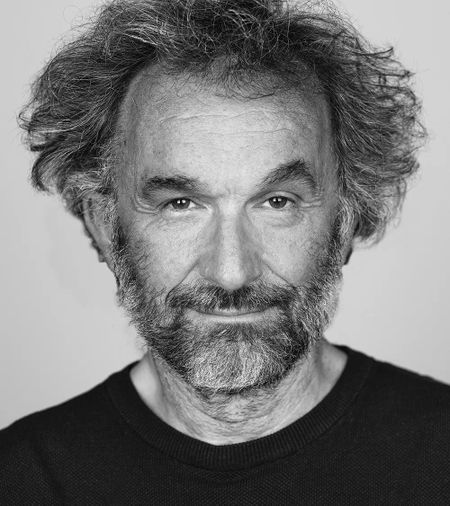

By Mark Allix

Read More: Engineering News, LSE, Business Times