OBITUARY

Norman Levy: A passionate champion for liberation, public service, and for the humanity in everyone

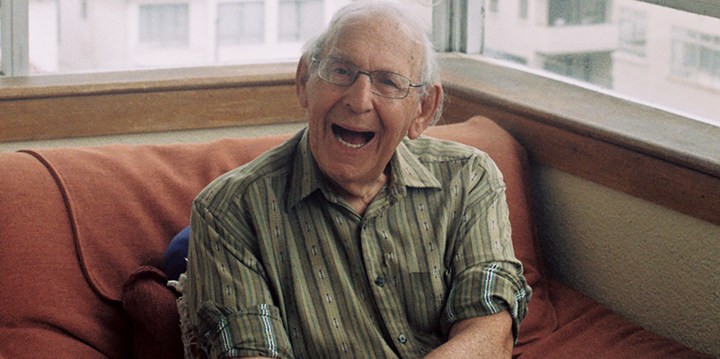

He was spirited in a way I have come to associate with the activists of his generation: they had indeed set out to change the world, believing they could, and in many ways they did.

Norman Levy, who died at the age of 91 last week, “literally fell into politics at the age of fourteen,” he writes at the outset of his memoir: this was “a happening that set my life on a path to prison, exile and finally return to South Africa.” It was February 1944, and he had taken his older brother’s bicycle for a ride from their Yeoville home to Hillbrow and slid to the ground when he ran into an unexpected street-corner meeting. As he got up and dusted himself off, he noticed that a white woman, in a clipped English accent, was addressing a small knot of black domestic workers as bemused white people looked on. A young man, who introduced himself as Ginger Lieberman, told Norman that the speaker was Hilda Watts (soon to be Bernstein), a Communist Party candidate for the Johannesburg City Council, and invited him to the next meeting of the Young Communist League. Norman went along, and found himself in the company of Ruth First, Joe Slovo, Ahmed Kathrada and others: “together we were comrades, ready to change the world”.

Norman, left, and his brother Leon enter the Johannesburg Drill Hall as co-accused alongside Nelson Mandela and 153 others in the Treason Trial. (Photo: Courtesy Levy family)

One of these comrades — albeit not in the YCL with him — was his identical twin, Leon, who survives Norman. The photograph with this essay shows the Levy boys, aged 27, entering the Johannesburg Drill Hall, as co-accused alongside Nelson Mandela and 153 others in the Treason Trial. The brothers believed that Norman was dropped from the trial because they were able to confound police officers: “The security police never quite sorted out which twin was carrying out the unlawful objectives of which potential unlawful organisation,” writes Norman in The Final Prize: My Life in the Anti-Apartheid Struggle.

Leon remembers the 5am knock on the door of their Yeoville flat on 5 December 1956. Their mother Mary answered (their father, Mark, had died when they were children): “Which one?” she asked, unprompted. “Both,” the security policemen responded. “It was awful,” Leon recalls. Mary had recounted her own experience of discrimination in her native Lithuania and raised her children in a “Bundist” (Jewish socialist) milieu. In 1965, neither son was able to attend their mother’s funeral: Leon had gone into exile after having been the first person to be held under the new 90-day detention law; Norman was in jail serving a three-year sentence, having been tried with Bram Fischer and thirteen others for being a member of the SA Communist Party.

Leon was a trade unionist: while still in his twenties he became president of the SA Congress of Trade Unions, a key organiser of the Congress of the People and drafter of the Freedom Charter. He was nicknamed “Tsaba-Tsaba” by black comrades, after the dance, for his frenetic energy. Always more low-key, Norman was affectionately called “Mahlalela”, “the loafer”. He was nothing of the sort. He was a fervent party operative, a Defiance Campaign organiser, and a leader of the African Education Movement. He describes, in his memoir, his “schizophrenic” life shuttling between his day-job, as a teacher in a well-endowed white school, and his extracurricular work running “Cultural Clubs”, to teach the thousands of black children whose parents were attempting to boycott, and then supplement, the newly imposed Bantu Education.

The clubs were political theatres, workshops and classrooms rolled into one, he writes. Despite his inexperience, he was instrumental in devising both the pedagogy and the logistics of these — primarily with his friend Helen Joseph, and ANC youth leader Robert Resha. The three travelled the country squashed into “Congress Connie”, Joseph’s beloved Mini-Minor. Joseph recalls giving the cops the slip in Uitenhage — and instructing Norman to hide in the back when a white petrol attendant became suspicious so that she could pretend she was the “Madam” and Resha her driver. Norman recalls the physical discomfort of the journeys, the amicable arguments, and Resha’s “noble” attempts to teach the tone-deaf Joseph how to sing freedom songs.

After the banning of the liberation movements in 1960, Norman worked full time as an underground party organiser; this is what led to his arrest in July 1964, and subsequent imprisonment. By this point, he was married — to fellow activist Philippa Murrell — and had two children, Deborah (five) and Simon (eighteen months), as well as an older stepson, Tim. It had been snowing the day before, and he had built a snowman in his front garden with the kids. When he was taken away the next morning, “the snow statue still stood in the garden and would eventually melt but it lingered in my mind, an icy metaphor foreshadowing four seemingly endless years ahead”.

Norman was subject to a horrendous fifty-four days in solitary confinement, much of it spent in brutal ‘standing interrogation’: he kept himself sane by convening imaginary conversations with fellow activists: “Ruth First, Joe Slovo and Moses Kotane were an awkward imaginary trio, thoughtful, zealous and cool as a cucumber — in that order.” He would “rather die”, he writes, than give up the names of his fellow cell-members in the Party, one of whom was Philippa. He had already been preoccupied with the difficulty of balancing family life and his political obligations — he had, in fact, written a play about Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, and their letters to their sons while they were on death row in the United States. When he was finally charged and sentenced to three years for furthering the aims of a banned organisation, he felt that “sentence had been passed on all of us, the families too. Philippa was left to pick up the pieces”.

While Philippa “played us Pete Seeger and Joan Baez records and kept us calm,” his daughter Deborah told me, “explaining to us that our father would return and why it was he was in jail”, Norman joined a small group of white political prisoners at Pretoria Local. These included the Rivonia Trialist Dennis Goldberg and, when he was finally caught, Bram Fischer. In his own memoir, his fellow inmate Ben Turok described Norman as disconsolate and critical of the movement’s leadership outside. With the sense of introspection that I came to know in Norman personally in his later years, he says in The Final Prize that it took him time to learn how “to mask one’s irritation at times, to share, and to trust”. He remembers fiercely, and describes beautifully, the bonds of kinship forged with these men — and his despair at the physical loss of his own blood family.

He describes, with equally poignant beauty, his homecoming upon release. Simon, now five, had preoccupied himself in the moment with “a dead sparrow he had found upon the grass and was stroking. He knew I was there, but said nothing. Perhaps I should have helped him bury the bird, but I simply stood there unable to do anything but watch him fondle the lifeless creature and wait. It would take us all time to thaw.”

In her own memoir, Things I Don’t Want to Know, Deborah Levy recalls the day:

My father is standing in the garden. His face is pale grey, like dirty snow. Only his eyes move. His arms hang stiffly by his sides. Dad is back, so very still and silent.

He looks like he has been hurt in some way. Very deep inside him.

“Daddy, the cat died while you were away.”

He squeezes my hand with his cold fingers.

“It’s lovely to be called Daddy again.”

The family went into exile, on an exit permit to the United Kingdom, and struggled to settle. Norman worked three different teaching jobs at one point, as well as his ongoing work in the movement, which focused primarily on finding educational placements for exiles to study abroad. Philippa was a vivacious and creative force, an artist and a writer: she and Norman had fallen passionately in love in the forge of the struggle, when liberation seemed possible. They had a third child, Jessica, in Britain, but their marriage did not survive the duress of separation and then exile, and Norman left the family home. He enrolled at the London School of Economics and earned a PhD in Economic History on the mining industry. He was appointed to a post, which he kept until his return to South Africa, at Middlesex University.

In his teenage years, Norman had responded to the times as any curious, thoughtful, young person might. Looking back on the roots of his political commitment, he writes that while it would be “crass to contrast my situation with the poverty of black children”, there were times when his family’s own “circumstances were too badly stretched for me to ignore the parched quality of our lives.” When Stalin died in 1953, he plastered the walls of his bedroom with posters of his hero. When he arrived in England in 1968 fresh from incarceration, he was irritated by the student protests which he thought self-indulgent (he later admonished himself for this), but he was attracted to the “Prague Spring” and Alexander Dubček’s “socialism with a human face”. Voicing this to his comrades, he found himself iced: he might have gone to jail for being a communist, but now, for over a decade, he would be “overlooked” — as Brian Bunting chillingly put it to him — and not invited to join the party-in-exile.

And so, rather than gaining exposure to official Marxism-Leninism in Moscow that other party leaders experienced, Norman found himself leading a student tour (on a refurbished London bus of all things!) to his much-idolised Soviet Union in the summer of 1972, staying in campgrounds and meeting ordinary people: “I liked the informality and casualness of our trip and enjoyed the unpretentiousness of the people we met.” He might have been “overlooked” by the apparatchiks, but this was his interest and his milieu: the “human face” of socialism, the lives of ordinary people.

Later, he would chair the Communist Party in London and join a delegation of social scientists to Moscow, finally staying in the Oktober Hotel. He would also go to the party’s storied 1989 Cuba congress as a delegate. But when he returned to South Africa in 1991, it was with his characteristic diligence and humility.

He worked on affirmative action frameworks at the Convention for a Democratic South Africa (Codesa), and ran the Community and Labour Studies programme at the University of Durban Westville. In 1996, Nelson Mandela appointed him deputy chair, under Vincent Maphai, of the Presidential Review Commission for the Transformation of the Public Service. For two very busy years, he ran the commission and co-wrote its report with Maphai. “I revered him,” Maphai told me. “It made such a difference having this towering giant next to me, someone who understood things politically. His starting point was that politicians come and go and that the core of government is the public service.” He argued passionately for a professional public service, and “he was persuasive”.

So much for that. Norman was critical of the cadre deployment policies of the ANC and infuriated by the Zuma kleptocracy — “disappointed, rather than disillusioned”, his brother told me. The twins, living a few blocks apart in Sea Point, would mull things over during frequent visits and phone calls: “We were very interested in whether we were in a ‘post-liberal’ era where democracy and democratic structures were less appetising to politics and parties. He felt it was too early to tell, and kept his faith in South Africa’s love of the Constitution,” Leon said.

If Norman kept to his ideals, the notion of “socialism with a human face” described his own approach to life well. He was, says his daughter Deborah, “deeply curious about what makes people tick, and what motivates them to behave what they do”.

He approached this project with much empathy: “I found him incredibly understanding and unjudgemental,” his friend Penny Busetto said. “He had this deep understanding of the struggling, suffering human, perhaps because he had struggled himself. I was amazed how he could always see the good in anyone — even racists.” In his final years, he became increasingly interested in psychoanalytic theory and, with Busetto, had an informal study group on Frantz Fanon, whose biography he had read.

He was, nonetheless, insistently diffident about himself: “One would never know his role, his commitment, unless it came out in conversation, and then he would be very matter of fact and downplay it”, says his friend Stephanie Urdang, who like him went into exile in the 1960s. “And yet his brilliant mind, his empathy, his understanding of the complexities of establishing a new South Africa, his disappointments and what they meant in terms of the arc of South African history, were always expressed with clarity and even humility.”

Like all his friends and family, Urdang found him to be “always interested in others, asking questions, wanting to know our stories”. This was my own experience of him, in the limited way I came to know him in his last years. He was an ideal conversationist, bristling with curiosity and eager to engage, full of his own ideas but always interested to hear others’ too. He was playful, too, and loved to laugh. He was spirited in a way I have come to associate with the activists of his generation: they had indeed set out to change the world, believing they could, and in many ways they did.

“My father argued passionately in what he stood for, and hoped it would make an impact on what we believed,” says his son Simon — an artist — of his parenting style. “But we were deeply encouraged to make decisions for ourselves, and grow up with our own ideas of what we should stand for.”

A painting titled ‘The Twins’ by Simon Levy, of his father Norman Levy and uncle Leon Levy. (Photo: Courtesy Levy family)

Deborah recalls that “he liked nothing better than the family around the table of an evening. He didn’t really choose a life that made that possible a lot of the time, but when it happened it was important to him. The dinner table was full of laughter, and discussion, and disagreement. It was important to have that. There was never really silence.”

Norman’s children “understood we were sharing our dad with the struggle,” Deborah said to me, “and we felt proud of the big purpose of those years. He went to jail when we were children, and then after the unbannings in 1990, he packed up thirty years of life in Britain as it if were some kind of stage set, and returned to South Africa. We’ve said goodbye to him many times in our lives, but we always got to say hello again. It feels bad not being able to do that, this time.”

Norman found deep love with his second wife, the American academic Carole Silver, whom he met and married in 1991: they lived between New York and Cape Town until she died, of cancer, in 2015. His three children and his four grandchildren live in Britain, but Simon was with him for the last two and a half months of his life, and — despite Covid restrictions — Deborah and Jessica were able to visit. He had lung cancer. On his last night, he lay in bed with Simon and listened, for hours, to one of his favourite pianists, Dinu Lipatti. A few hours earlier, alert to the end, he had managed to participate — despite his confusion — in a spirited discussion, with his son and Penny Busetto, about Jacob Zuma’s fate. As always, he has an opinion: “It’s up to the courts!” he managed to say. DM

Mark Gevisser’s most recent book is The Pink Line: Journeys Across the Worlds Queer Frontiers.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.