AGE OF ANARCHY

Riot Control Training 101 — a memoir

Years ago, the writer learnt about riot control tactics first-hand — from both sides of the barricades. Recent events in SA have encouraged him to revisit those drills and the tactics he learnt.

Not surprisingly, given the circumstances in South Africa now, earlier today my wife and I were discussing the violence as well as the newly ordered deployment of the South African National Defence Force (SANDF). This deployment is now being carried out in several parts of the nation in response to a growing tide of violence, looting, and more general civil turmoil. What, exactly, SANDF personnel are going to do, what kind of orders and assignments will they have, what training might they have had, and how they will carry out their mission all became big questions in our conversation.

As it turns out, improbable as it may seem to some, I actually had first-hand experience (and training) in demonstrations and riot/crowd control efforts — and from both sides of the barricades. Through the early part of the 1970s, university student protests against the Vietnam conflict were becoming increasingly routine on many US campuses, and those were in addition to a series of major protest rallies in Washington, DC with hundreds of thousands of participants.

There were obviously several motivations for such protests. First, this included a growing revulsion over the ever more senseless progress of the war. In addition, there were fears on the part of many male students about a growing likelihood they would be drafted into the army. With half a million troops in the theatre of combat, it almost inevitably meant they would be fed into the meat grinder of the conflict.

To get an approximate feeling of what it felt like back then, there are many films that offer insights into the psychological flavour of those times and events, and their consequences. These range from The Deer Hunter to Good Morning, Vietnam to Full Metal Jacket to Apocalypse Now, in addition to MASH, which, although ostensibly about the Korean War, was really a protest over the insanities of Vietnam.

Back in 1970, I was working three different part-time jobs to pay for my university studies. Given these pressures, I was falling behind in my coursework. I dropped a course or two in an effort to have sufficient energy to concentrate on the remaining classes. That meant I had entered the danger zone of having insufficient course credits to achieve the minimum number of credits needed to keep me as a full-time student in good standing — in the basilisk eyes of our local military draft board. (These boards operated county by county.)

Where I was registered for the draft at the time, Montgomery County, Maryland, so many men my age were still in university studies that the board was finding it hard to meet its quota of men eligible for drafting into the army. When the government instituted the national draft lottery based on birthday dates, my predicament only got worse as my draft lottery number was 6 out of 366, meaning I was now an inevitable draftee unless I had an alternative that kept me out of harm’s way.

Getting a draft deferral on the grounds of a mental defect, as Arlo Guthrie did, or from any pre-existing physical condition seemed unlikely since I didn’t have one, other than a desperate desire not to die in “The Big Muddy”. Conscientious objector status required much more than a declaration, and fleeing to Canada seemed ill-advised if I ever hoped to work in a rational national government in the future. Accordingly, the only real alternative left was enlistment in an Army Reserve unit or a National Guard unit.

That may require a bit of explanation. The Army Reserve was a real army, comprising units of fully trained men, but who were not on active duty status unless their units were called up in an emergency. The National Guard was the direct descendant of the old colonial-era militias of the individual states and it too comprised men who had been fully trained in their respective military specialities (from cook to tank corpsman), but whose units were ostensibly under the command of state governors.

These National Guard units could be called up for service when a natural disaster occurred, or when it seemed inevitable that severe civil unrest would overwhelm local police forces. In extremis, the National Guard units could be federalised for service directly as part of the national army. Perhaps the most noteworthy circumstances were when National Guard troops had been called up in some Southern states to enforce the contested integration of previously all-white universities or schools.

When a National Guard unit was federalised, it effectively came under the command of the president, just like any other regular military unit. The only real difference was the relative lesser likelihood of being called up to serve in a foreign conflict like Vietnam than those in a regular army or even army reserve units. (Now, in fact, reserves and National Guard units are so thoroughly integrated into the US’s overall force structure that most of those units have served in Afghanistan and Iraq since 2003, just as with regular, active duty units. Thus, the distinctions between the three categories have become increasingly less consequential in the country’s all-volunteer military structure.)

So, having heard from my local draft board that I would be drafted in four days’ time, I devoted the next three days to finding an Army Reserve or National Guard unit that had an opening in which they could take a new recruit — immediately. As it turned out, one National Guard unit had a vacant spot, and they agreed to issue my induction papers immediately, but would forestall my being shipped off to basic army recruit training until the end of the current university semester. When it began, it meant I joined army basic training in midwinter (with all the endless marching, bayonet training, rifle range training, and so on). Later, I went into my military speciality as a food service specialist, building on my illustrious career as a waiter and fill-in cook in a restaurant over several years.

Oh, did I forget to mention that in May 1970, months before the beginning of my military career, I had been badly beaten up by the Maryland State Police during an anti-Vietnam War demonstration, on my own college campus? The turmoil lasted until the Maryland National Guard was activated by the governor of the state to quell the disruptions. A unit of fully trained, well-armed, well-disciplined, well-equipped National Guard is a much different opponent for protesters than a rowdy bunch of state police, eager to beat up or tear gas a few thousand rowdy students. And as it turned out, ironically, the National Guard unit I joined had been one of the battalions that had occupied my campus that spring.

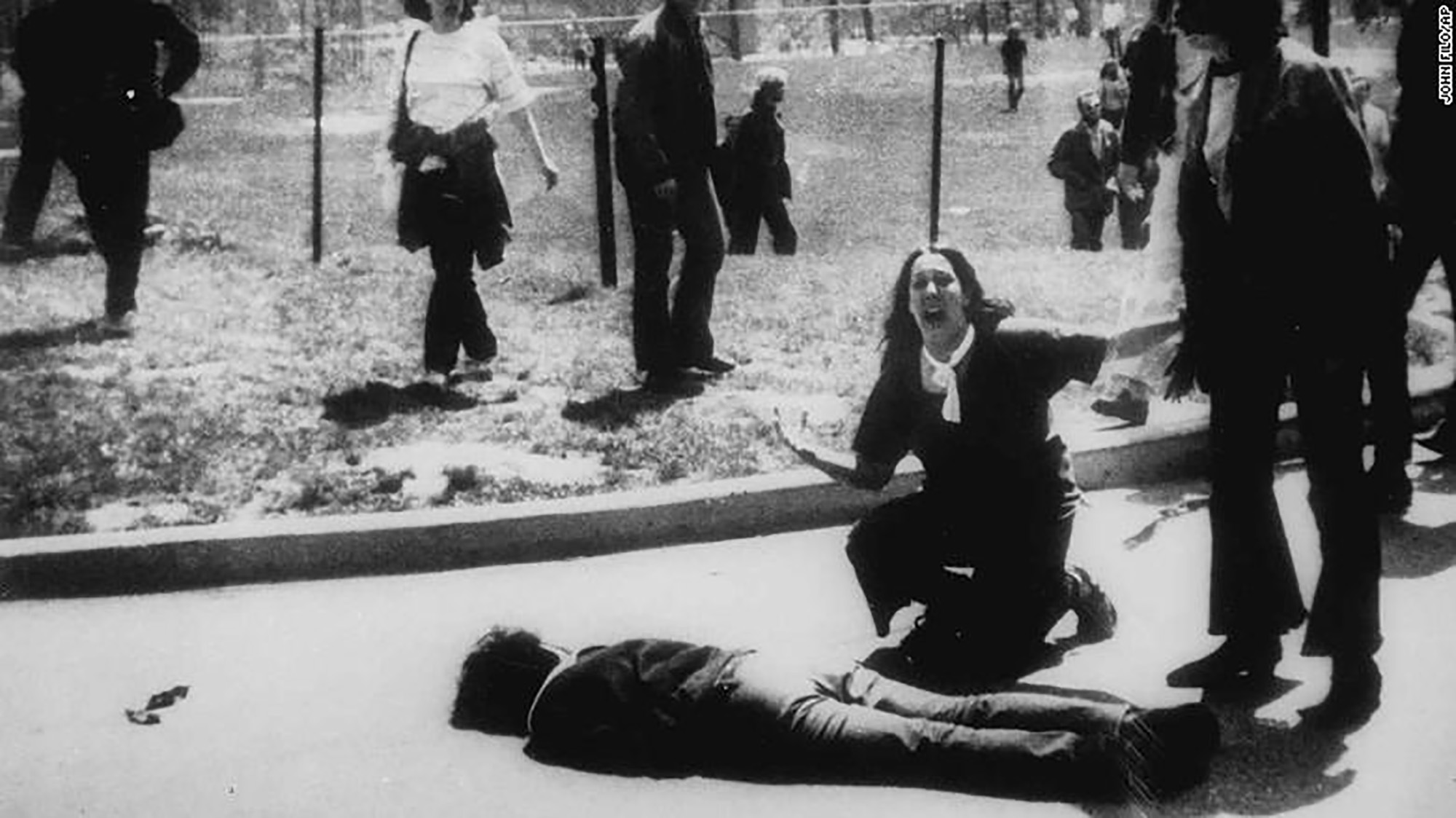

Mary Ann Vecchio gestures and screams as she kneels by the body of a student, Jeffrey Miller, lying face down on the campus of Kent State University, in Kent, Ohio, 3 May 1970. (Photo: John Filo)

In my active-duty basic training, we did all the usual military things with rifles, grenades, classes in military law, and long-distance conditioning marches. But precisely because of the killings of students by some poorly trained Ohio National Guardsmen at Kent State University and two other students at yet another school in the South, and in response to some near tragedies elsewhere in 1970, our training units were some of the early ones being thoroughly drilled in the anti-riot/crowd control tactics being rolled out to National Guard units across the nation.

There was only a small amount of theory in that training; rather, it was grounded in repetitive, simulation-based training. As a result, on one day, in the morning, half of us would be ordered to dress up in a vague approximation of student garb, while the other half would be shaped into units whose task would be to control the faux students. In the afternoon, after a quick lunch, we switched roles.

As students, we were encouraged to scream and insult our fellow trainees (but not throw rocks or Molotov cocktails at them), while the military trainees were instructed to stand their ground firmly behind those clear plastic shields, with their rifles, bayonets and riot control batons at the ready. Alternatively, the drill would be to move the fake students by using close-order, diagonal echelon movements towards an enclosure or away from a target, or to advance in force in order to break up knots of protesters into individuals who could then be arrested or allowed to disperse, depending on the point of the particular drill on that day.

The idea was that riot control tactics were the opposite of attacking an enemy position with the intention of killing them all off. The enemy in this case was still fellow citizens who still had rights. There was, of course, also practice in laying down a blanket of tear gas against demonstrators, while the uniformed soldiers had deployed their gas masks ahead of time.

The vision of several hundred identically uniformed soldiers, bearing weapons, steel helmets and wearing gas masks, carrying shields or riot batons, and marching in unison behind a barrage of tear gas was almost certain to give the less rigorously drilled students pause, and to then trigger an urge to flee, that is, unless they were truly intent on overthrowing the rule of law.

The key, too, based on the recent Kent State disaster, was for the soldiers not to carry loaded weapons. Ammunition magazines were kept out of weapons to avoid any mistakes. Thus, no more campus incidents that could become international news stories.

And so, day after day, we trained, acting either as protesters or soldiers and then switching roles. Despite the fact we knew we would change sides after lunch, acting as pretend students never quite reached a comfort level sufficient to gain any tactical advantage over one’s fellow uniformed, well-equipped trainees — even with opportunities to scream obscenities and lob the occasional bit of rubbish at them.

And then, after all that daily drill for two weeks, I was discharged from my active-duty status, and I returned home, but now armed with my hard-won tactical knowledge about civil control. Then, amazingly, a short time later, I was actually called up for active duty to help tamp down yet another unruly anti-war demonstration on my own university campus.

This time, rather than as a student, I was a private first class in the Maryland National Guard. Fortunately, I was usually found serving in the unglamorous, but necessary role of preparing meals and feeding the troops from our well-equipped field kitchen, despite my certified, up-to-date knowledge of approved crowd control techniques. Still, the old military genius Napoleon was right, an army does march on its stomach, even if it was just carrying out crowd control duties, keeping public roads open and the campus buildings from being trashed and looted

This personal experience now forces me to consider whether the police and the newly activated military in South Africa actually have the numbers, the equipment, the training, and command coordination necessary to carry out effective public order policing and control of looting. In the previous decade, the country witnessed an appalling version of public order policing in which there were numerous fatalities and injuries with volleys of live ammo rounds fired at protesters in Marikana.

Is there any evidence that law enforcement training, coordination and capabilities have dramatically improved in the ensuing years until today? Moreover, is there a clear strategic approach to containing and ending looting and violence — let alone in dealing with the deeper, underlying factors that stem from economic, social and political distress? On that, the jury clearly is still out. DM

The uncomfortable reality is that the SAPS deserted their posts oin Gauteng and Durban malls, leaving the communities and businesses to fend for themselves.

More than 120,000 SPS police officers, 74,000 SANDF permanent army personnel (not to mention tens of thousands of metro police) are clearly unfit, under trained, ill disciplined and incapable of defending justice, the rule of law and of property. Watching them waddle their overweight body around, without masks and flicking their fast food into public streets with impunity, is indicative of the state of motivation and discipline in their minds and ranks.

BBBEE has pushed the incapable but connected far ahead of the competent in all spheres of society, and the dividend we pay is an expensive, incapable and inefficient “failed” state. These soldiers do not even know how to safely cary a weapon – let alone be able to calmly choose targets and avoid fear under fire.

Looters equipped with streams of new vehicles in Durban are clearly not “”the poor” narrative, nor is the insertion of the EFF and Zuma supporters into the melee coincidental.

The media is so busy blowing up its hero Cyril Ramaphosa, it refuses to acknowledge the elephants in the room.

Only once the malls that are easily looted, lie bare, will looting stop. For now. And who ultimately, pays to rebuild and restock them? Me and you. Meanwhile, Ramaphosa, Zuma and Malema continue to enjoy their BBEEE billions.

That’s our reality, black or white.

Like the author, I was caught up accidentally in the riots in Istanbul a few years ago. Edrogan’s riot control police were very well trained and although they struggled to control the demonstrations, no major damage was done to property as the demonstrators were moved along with tear gas and truck mounted water cannon. Enormous rolls of razor wire funneled the demonstrators in the right directions. Why do we not have the same- this is not rocket science and this was always going to happen at some point.

Dear Cyril & Co – take note Brooks’ of experience. How about a National Guard?? This will give employment to hundreds of unemployed youth and give them some dignity. No money? Cut Ministers and Civil Servants salaries by 10% and get your butts into gear!!