OP-ED

Affordable housing crisis facing the working poor

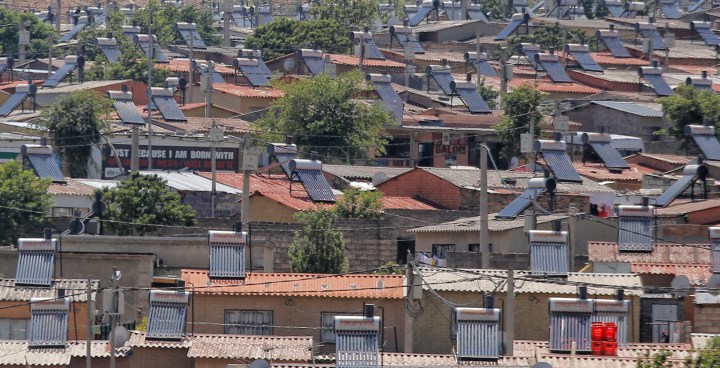

The frustration of working families unable to find affordable housing lies behind some of the recent land grabs. Housing policy has focused on building free houses for indigent households, and neglected the struggles of low wage earners to obtain decent homes.

People who should be able to afford reasonable accommodation are condemned to squalid and overcrowded conditions. Their exclusion from the formal property market contributes to mushrooming backyard structures and rising rentals.

What was once a housing crisis for unemployed and destitute groups now reaches deeply into the working population. People’s dreams of owning their own home have faded because they earn above the bare minimum to qualify for a free house, but too little to afford a property in the formal sector. The “gap” market has become a chasm.

Households earning between R3,500 and R15,000 a month conventionally fall into this category, but dwindling house-building, elevated house prices and high interest rates have pushed the threshold beyond R17,000. They include policemen, mechanics, bricklayers, secretaries and administrators. Despite stable jobs and steady incomes, their hopes of getting on to the housing ladder and accruing a family asset are receding.

A recent Financial and Fiscal Commission report showed a striking reversal in their fortunes compared with people eligible for free houses. More and more households fall into this income bracket, but fewer houses are being built within their price range.

It’s a systemic problem related to the growing urban population, the deficient supply of new properties and people’s inability to afford the available stock. Solving this conundrum will require a more elaborate housing policy and stronger partnerships with the private sector to address its multiple dimensions. The response needs to go well beyond the existing RDP/BNG housing programme.

For instance, people need help to get loans because housing is the costliest item most will ever purchase. Low earners are high risk to the banks because they struggle to manage their tight household budgets and many are saddled with debt. Historic dispossessions deprived many families of inherited wealth for collateral. Many have impaired credit records and will find it hard to repay their home loans. Less than one in 20 of all mortgages go to households earning under R15,000 a month, according to the latest Consumer Market Credit Report.

Financial regulations also encourage bank caution, with rules about the minimum earnings required to purchase properties in different price brackets. If a house is considered beyond a person’s reach, their application is automatically rejected. The cheapest new houses in cities range between R400,000-R600,000. People need to earn at least R17,000-R20,000 a month to qualify for a loan. Banks have the added concern that affordable houses won’t hold their value because of their location.

The price of new houses in desirable locations is driven up by high building costs and high land prices. These reflect inefficiencies in the development process, coupled with onerous regulations surrounding the planning, design and execution of new projects. Excessive and unco-ordinated regulations create bottlenecks and make even the cheapest formal houses unaffordable to gap-market households. Red tape needs to be streamlined and more creativity encouraged, such as micro-housing, which is booming in other parts of the world.

A decade ago the government introduced several separate schemes to improve access to affordable housing, but their individual and aggregate impact has been small. The main scheme for buyers to enter the gap market is the Finance Linked Individual Subsidy Programme. It offers people earning between R3,500-R15,000 a month a one-off subsidy to reduce the amount they have to borrow by between R10,000 and R87,000, depending on their income. But the subsidy is too small to help. Most still can’t afford even the cheapest houses.

The programme also ignores people’s other debt burdens and general budgeting difficulties, so the banks remain cautious. Administrative inefficiencies compound the low uptake. Against a target of providing 70,000 programme subsidies between 2014 and 2019, only 4,400 were dispersed after three years. It has clearly failed to make much inroad into the problem because of its limited scope.

The government is now revising the policy and is likely to increase the subsidy amount and speed-up its procedures. But a one-off adjustment will soon lapse because of inflation, so it could be back to square one. Additional measures are needed to strengthen working families’ effective demand for housing.

Low earners would benefit from practical support to clear their debts and to build up a track record showing they are credit-worthy to bank lenders. We recently studied a government scheme that helps people to rent their home at first and then to purchase it later. During the subsidised rental period, people learn to juggle their finances, establish a positive credit record and accumulate some savings towards a deposit. They take on responsibility for maintaining the property and paying the service charges to show they can repay a future bank loan. Although the scheme has had challenges, we believe its basic principle of rent-to-buy is worth preserving.

A good case can be made for revising the Finance Linked Individual Subsidy Programme policy and linking it to an improved rent-to-buy scheme. Government support for rent-to-buy would have a bigger impact on the gap market by helping a wider group of working families to overcome the obstacles they face to accessing housing finance.

Additional measures are required to expand the supply of inexpensive homes. This is another big agenda, including more innovative house designs, more appropriate building standards, more flexible regulations and simpler approvals. A burgeoning urban population needs more determined efforts on the part of government and the private sector to deliver affordable housing closer to jobs and amenities. DM

Professor Ivan Turok is executive director and Dr Andreas Scheba a research specialist at the Human Sciences Research Council.