OP-ED

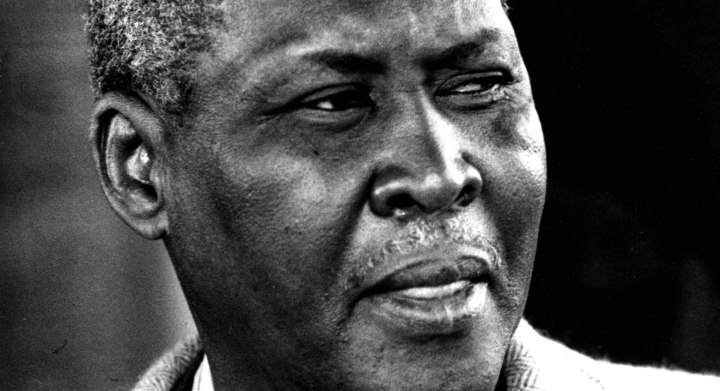

Leadership in Question (Part Six): Chief Albert Luthuli, leadership and service

The life of Chief Albert Luthuli bears lessons of considerable relevance to South Africa’s crisis of leadership. His understanding of ethics, service and willingness to sacrifice were carefully considered and articulated in a manner that needs to be studied and imparted to the present generation.

This article first appeared on Creamer Media’s website polity.org.za. It is part of a series on leadership. Read parts One, Two, Three, Four and Five.

Some of those who have read my work may be weary of the continual return to Chief Albert Luthuli. I do so because his life has a bearing on some of the most important issues of our time, questions that continue to bedevil our relationships with one another and the qualities of leadership that we seek.

Luthuli’s life has relevance to the scourge of violence and the status of nonviolence, and the value placed on peace in our lives, the relevance of religious beliefs in a secular society, questions of masculinity and gender equality, ethical leadership and the question of service, and the interrelationship between numerous identities and communities that coexist in South Africa. It bears on bravery, but not the bravery of the daredevil. It is a bravery that is carefully considered and requires preparation. This leads to a willingness to sacrifice, even to the point of offering one’s life in the service of freedom.

(To my knowledge, there are three biographies of Chief Luthuli, that by Mary Benson, Chief Albert Lutuli of South Africa (London: Oxford University Press, 1963, which is very brief and long out of print, one by Scott Couper, Albert Luthuli. Bound by Faith (UKZN Press, 2010), which is devoted to rebutting any suggestion that the chief may have accepted armed struggle and also dismissing the suggestion that there may have been foul play in his death. The third biography, on which I place greatest reliance, is Robert Trent Vinson, Albert Luthuli. Ohio Short Histories of Africa. 2018. Vinson and I appear to agree that the chief reluctantly accepted the formation of uMkhonto weSizwe (MK) and the armed struggle.)

In an otherwise rather empty January 8th statement in 2021, the ANC remembered that it was the 60th anniversary of Luthuli being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize (along with a range of other milestones in the lives of other heroic figures and in liberation history). On the 50th anniversary, in 2011, the year was filled with references to MK’s anniversary and hardly a mention from the ANC or its allies of Luthuli.

This neglect of Luthuli as a leadership figure is unsurprising since his life has meanings that are very relevant to rebuilding South African democratic life, on which there is ambivalence. This ambiguity relates to those, many of whom are still in leadership, of Luthuli’s organisation, the ANC, who have dedicated themselves to stealing from the poor and who are quick to voice the qualities of selflessness and service when they have no intention of acting these out.

Luthuli’s Christianity

No one can engage Luthuli’s life without considering his theology. His active Christianity, liberation theology before the announcement of that doctrine, was at the centre of his life, guiding his every action, whether in the home, in relation to the apartheid regime, as an elected chief of a community comprising mainly non-Christians, in his relationship with his children and in his marriage.

Luthuli articulates this when he writes:

It became clear to me that the Christian faith was not a private affair without relevance to society. It was rather a belief which equipped us in a unique way to meet the challenges of our society… I had to do something about being a Christian, and that this something must identify me with my neighbour, not dissociate me from him. Adams [College, where he studied and later became a teacher] taught me more. It inculcated, by example rather than precept, a specifically Christian mode of going about work in society… (Let My People Go, henceforth referred to as LMG, Tafelberg. Cape Town, 2006., p 28)

His religious beliefs are interpreted as aiming to ensure that “God’s Will, holy and perfect, be done in South Africa, the dearly loved land whose children we are” (LMG at p. xxvi). The notion of “perfection” is interpreted in relation to Luthuli’s reference to “divine discontent”, both of which are linked to confronting an “imperfect” world where human beings made in the image of God are treated with contempt and exist in conditions of inequality.

Luthuli was never resigned to oppression, evoking the Exodus refrain “Let My People Go”. Insofar as some hesitated or like the people of Israel worshipped false gods (in this case apartheid blandishments), he asks in a speech of 1953: “Must we fold our hands in despair when we see our people drift to ultimate impotence and perpetual slavery? God forbid that we should be so untrue to Africa and the cause of Freedom!”

Not a moderate, but a militant

Although Luthuli is often depicted as a “moderate”, this firmness and unwillingness to accept half loaves instead of freedom is a constant theme in his statements. (See LMG at pp. 26,101 for example). He explicitly rejected the notion of being cast as a moderate and described himself as a militant:

He pointed out… that, contrary to popular belief, he was in fact a militant. He said categorically: “I am not a moderate – I am a militant.” He felt that to say he was a moderate gave his followers a wrong definition. A “moderate” would go to the government “cap in hand” and this would never do. “I am a militant, but in my militancy, I pursue the struggle along peaceful lines. It is better that we get our freedom with as few scars as possible.” (See In The Shadow of Chief Albert Luthuli: Reflections of Goolam Suleman, ed Logan Naidoo at 65. Suleman, along with EV Mahomed, provided logistical support to Luthuli in the many years when he was under house arrest. See also Vinson, Albert Luthuli at p. 14).

The gospel of service and preparedness to sacrifice

The title of Luthuli’s autobiography, as is well known, is derived from the Lord’s exhortation to Moses, which reads, inter alia: “Then the LORD said to Moses, ‘Go to Pharaoh and say to him’, Thus says the LORD, ‘Let my people go, that they may serve me’.”

Service, in Luthuli’s understanding, may be taken as meaning “serving faithfully” and can in this context be equated with what Luthuli repeatedly calls the “gospel of service”.

Clearly also from Luthuli’s understanding one can (as liberation theologians would later express it) only serve the Lord by serving justice. To serve the Lord is not service or submission in the sense of performing various rituals, but carrying out His Will as active human beings with full agency.

Related to this notion of Christianity, Luthuli’s ideas of leadership were in line with a much-abused phrase, “public service”. He lamented that people were too concerned with reward and slow in adopting the “gospel of service”. In a speech at the 44th Congress of the ANC in 1955 he exhorts the members to be willing to serve and sacrifice:

“But for all this we cannot claim to have prosecuted our campaigns with any semblance of military efficiency and technique. We cannot say that the Africans are accepting fast enough the gospel of service and sacrifice for the general and larger good without expecting personal and at that immediate reward. They have not accepted fully the basic truth enshrined in the saying, ‘no cross, no crown’.” (See discussion of the allusion to cross and crown in Raymond Suttner “The Road to Freedom is via the Cross” ‘Just Means’ in Chief Albert Luthuli’s Life”, South African Historical Journal, 2010, pp 694-715, at p 706, PDF available on request.)

Prophetic role?

The evocation of the Mosaic call raises the question of Luthuli being “called” by the Lord as a prophet. It is known that many who are called are reluctant to take up the prophetic role, as in the case of Moses himself. Luthuli describes his reluctance to accept the “call of my village” to stand as an elected chief. (LMG chapter heading). The notion of prophecy is not forecasting the future, but reading the “signs of the times”, which Luthuli does. South Africa’s distinguished liberation theologian, Father Albert Nolan, has written:

“Prophets are typically people who can foretell the future, not as fortune tellers, but as people who have learnt to read the signs of their times. It is by focusing their attention on, and becoming fully aware of, the political, social, economic, military and religious tendencies of their time that prophets are able to see where it is all heading. Reading the signs of his times would have been an integral part of Jesus’s spirituality.” (Albert Nolan, Jesus today. A spirituality of radical freedom. Cape Town: Double Storey Books. 2006, pp 63-4.)

Linked to the assumption of the role of a prophet, carrying out God’s Will and serving Him, was the need to be exemplary as a leader. One cannot execute God’s Will unless one tries to act in accordance with the perfection, manifested in a sense of justice, that he seeks. Luthuli believed he had to serve but also to do what he advocated for others – to lead by his own actions. He recognised that this could require preparing oneself for sacrifice, and the possibility of death.

Sacrifice and preparation

Sacrifice does not come naturally to anyone. It is necessary to ready oneself for sacrificing oneself. Nelson Mandela remarked that if one says one is prepared to die one must understand what that means and be willing to make the necessary sacrifices. (Long Walk to Freedom). This preparation and readiness for what he undertakes to do or how he understands his calling imbues Luthuli’s life.

The necessary preparation is illustrated in Luthuli’s reaction to the ANC Defiance Campaign of 1952. He had been elected to the ANC Natal presidency just before the onset of the campaign in 1951. The previous president, AWG Champion, had not informed the province of this among other national decisions. (LMG p 103). Just before leaving Natal for the national conference in Bloemfontein, Luthuli received written material from ANC headquarters, including (“to my astonishment”) suggestions and resolutions about a campaign of civil disobedience. (LMG at p 104)

At the conference he asked for the date of commencement of the campaign to be postponed because Natal was not ready. But “[t]his was no easy matter – my audience was unsympathetic. I well remember the interjection of one woman delegate when I tried to argue for a later date: ‘Coward! Coward!’ she shouted at me. It is better for me to express my cowardice here, I retorted, ‘than that I should keep silent and then go away and play the coward outside’.” (LMG pp 104-5).

Luthuli’s reflection on this incident is not only an ethical question but indicates his appreciation of the requirements of political organisation which needed adequate preparation, an issue to which he continually returns.

In reality, many provinces were not ready for the Defiance Campaign. “Outside the conference hall, however, some members from other provinces did confide in me that they were fearful that the campaign might suffer from preparation that was too hurried. This contradiction expresses a real dilemma. We have continually needed to act and act urgently. At the same time, ill-prepared action can be worse than none. The Congress movement cannot rely on occasional spontaneous demonstrations – too often these, coming at a time when patience has snapped for the moment, develop into violence. The people need to be briefed with clarity and care, and they must be given the opportunity to signify their willingness and readiness to participate.” (LMG p 105).

This illustrated that the “gospel of service” needed to be implemented in a very practical manner in a range of campaigns and other activities. Luthuli’s organisational sense was little different from that of other leaders who were political organisers, like Walter Sisulu, although obviously Luthuli’s location in Groutville and the restrictions imposed for most of his political life set limits on what he could do directly and openly.

Acting on this appreciation that commitment to the Defiance Campaign, where people had to be ready to face imprisonment (or even death in the view of some), needed proper understanding and preparation (Sisulu refers to this in relation to the volunteers in the Defiance Campaign being known as “Defiers of Death”. W Sisulu, I Will Go Singing: Walter Sisulu Speaks of his Life and the Struggle for Freedom in South Africa, in conversation with GM Houser and H Shore (Cape Town and New York: Robben Island Museum and the Africa Fund, nd., c. 2001), p. 79.), a meeting was held to decide whether leaders in Natal were prepared for the requirements of the campaign. They had to take the pledge that Congress required. Mary Benson describes the situation:

“Among the gatherings about the country when Congress leaders and their followers took the pledge, was a small meeting in the bare rooms of the ANC offices in Durban in the busy Indian shopping centre. The new President of the Natal Congress, Chief Luthuli… said to his Executive, ‘Look, we will be calling upon people to make very important demonstrations and unless we are sure of the road and prepared to travel along it ourselves, we have no right to call other people along it’. MB Yengwa… described what happened after that: ‘We said we were prepared and he said he too was prepared, and he asked us to pray. We gave our pledge and we prayed.’” (Mary Benson, South Africa. The Struggle for a Birthright. International Defence and Aid fund. London 1985, 144-5).

Luthuli, like Mandela and others (Chris Hani in a later generation) understood that willingness to undergo a sacrifice involves also a sense of personal readiness that requires a different type of preparation from purely rational understanding, including introspection. One may understand some duty to do something at an intellectual level, but still not be ready to do it because one has not internalised what the sacrifice entails and whether one is ready to undertake it. (On Hani’s interrogation of the psychological state of MK soldiers about to cross the border, to ensure their readiness, see, among others, an interview with former camp commander Dipuo Mvelase, 1993, available on request).

The rational and passion/emotional components in sacrifice

It is important for us to reflect on what sacrifice means, in this example and beyond. It is still an important question and also integral to the personality of Luthuli. It does not go automatically with being a leader or a cadre or a pastor. One may know the bible or Marxism or other belief systems very well, but that rational understanding or knowledge of texts and their range of meanings is not necessarily coupled with being ready to act out one’s decisions, to embrace the spirituality, passion or emotional element required to go through with one’s commitments in situations of hardship or in facing death.

Very shortly after the initiation of the Defiance Campaign, Dr JS Moroka, then president of the ANC, faced trial with other leaders and he sought a separate defence and distanced himself from his co-accused. There are many such examples of individuals who may have been bold in one situation only to falter under certain types of pressure.

It may also be, and we may have witnessed this in South Africa with acts of betrayal by leadership after the fall of apartheid, that one may form a connection with the oppressed, adopt the “option for the poor” (in the language of liberation theology) at one moment but sever it at another, be tempted by something or fear some consequence and then rupture that which connected one with the poor and marginalised. (See Raymond Suttner, Inside Apartheid’s Prison, 2 ed 2017, Introduction to new edition.) DM

To be continued in the next part.

Professor Raymond Suttner is completing work as a visiting professor at the Centre for the advancement of Non-Racialism and Democracy at Nelson Mandela University, Port Elizabeth. Suttner served lengthy periods in prison and house arrest for underground and public anti-apartheid activities. His writings cover contemporary politics, history and social questions, especially issues relating to identities, gender and sexualities. He blogs at raymondsuttner.com and his Twitter handle is @raymondsuttner. He is preparing memoirs covering his life experiences as well as analysing the political character of the periods through which he has lived.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Thank you Raymond, for this excellent and thoughtful piece. I loved your characterisation of Luthuli as a “liberation theologian” before its time. Your writing on Luthuli is an inspiration, and a reminder to those of us who have tried to straddle the world of faith and struggle of the profound example that he gave.