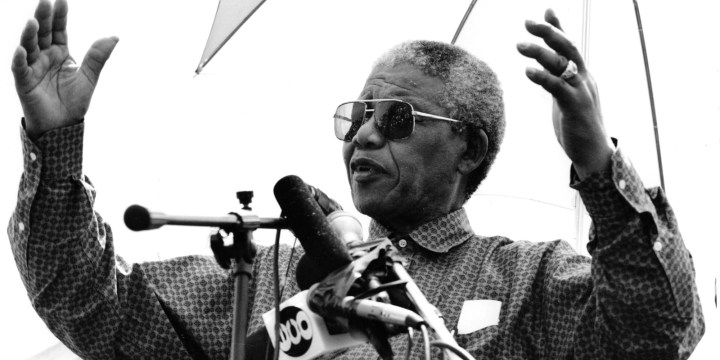

OP-ED

Nelson Mandela in Sudan: A historic 1962 journey

Nelson Mandela’s 1962 journey to Sudan was not only an important moment in Pan-African solidarity, it also saw him being granted a Sudanese passport.

There is a story circulated across Sudanese media as well as the literature on Sudan’s support for African liberation movements that Nelson Mandela was granted a Sudanese diplomatic passport when he visited Khartoum in 1962, which facilitated his tour to some countries of the African continent back then.

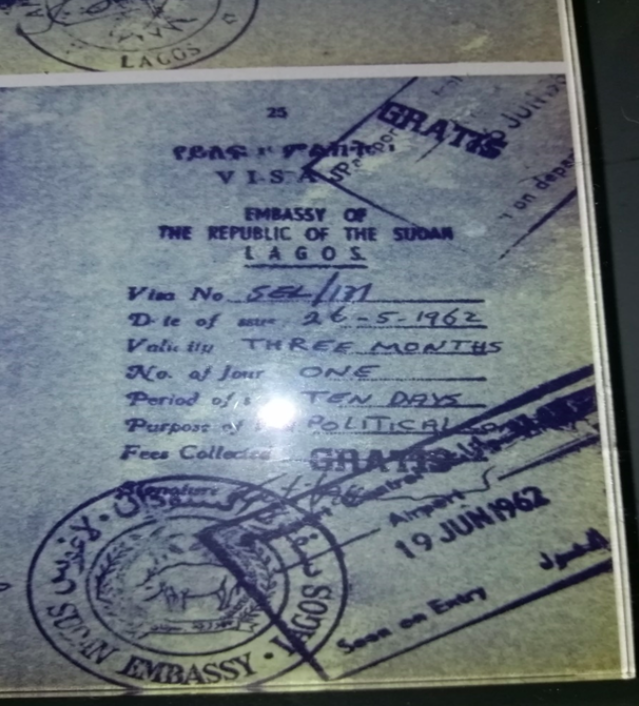

Mandela’s visa from Sudan Embassy in Lagos. (Photo: supplied)

This story is simplistic, on one hand, and lacks accuracy, on the other. It is simplistic because it tries to restrict Sudan’s significant support for the anti-apartheid liberation movement in South Africa to mere travel documents for the great freedom fighter. It is furthermore inaccurate due to the fact that when Mandela entered Sudan, he was actually carrying a passport with an entry visa from one of Sudan’s diplomatic missions abroad. It is true that he was granted a Sudanese passport, but that was in a bigger context, to be elaborated below.

In fulfilment of a pledge he made to carry out his struggle from within the country, Mandela never travelled outside of South Africa till 1962. When the ANC received an invitation from the Pan-African Freedom Movement of East and Central Africa (PAFMECSA), to participate in a conference to be held in Addis Ababa in February 1962, the ANC decided to send a delegation, headed by Mandela, to take part in this conference.

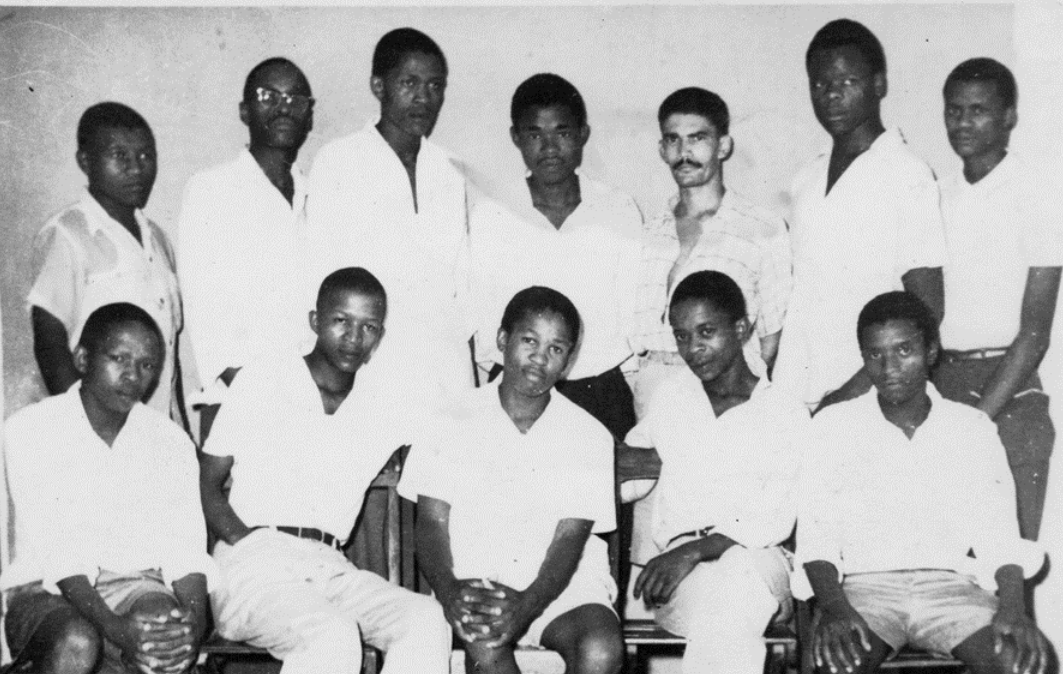

The youth Mandela met in Khartoum. (Photo: Twelve Disciples)

Mandela was encouraged and motivated to break his pledge and get out of the country in this mission because he saw in it not only a participation in the activities of the high-level Pan-African conference, but more importantly to take a tour in selected African countries with the aim to explain the cause of his movement’s struggle, and to seek political and financial support for it, as well as military training for its cadre.

Choosing Sudan among the countries that Mandela decided to visit did not come by chance. Sudan, being one of the first African countries to gain independence, adopted at the dawn of its early independence a policy to support the African movements pursuing liberation for their countries and freedom from colonialism.

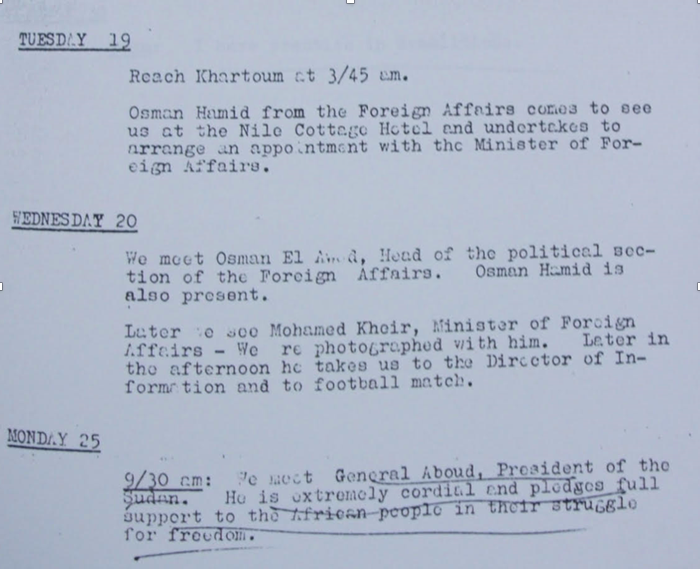

Diary of Mandela’s visit to Sudan. (Source: South African History Online)

In the case of South Africa, in particular, this policy had taken practical dimensions manifested in cutting off any economic or trade relations with the apartheid regime, denying South African planes and ships access to Sudanese airports and seaports. Furthermore, Sudan made a proposal, within a multilateral African framework, to militarily train the members of liberation movements on its soil. Emphasising the support of Sudan, Mandela mentioned the country twice in his speech of 3 February 1962 before the Addis Ababa conference, four months before his visit to Sudan.

In Addis Ababa, Mandela was offered a passport by the Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie to enable him to make his African tour. It was not possible for Mandela to get a South African travel document due to his political activities and skin colour. He therefore snuck into present-day Botswana and from there to Tanganyika, which gave him a letter allowing him to travel to Ethiopia.

Mandela used the Ethiopian passport on the tour that took him to North and West Africa. He visited Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Morocco, Mali, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Ghana and Nigeria. For security reasons, Mandela used the pseudonym “David Motsamayi” in his passport.

While he was in Nigeria, he visited the Sudanese embassy in Lagos to obtain the entry visa to Sudan. He was granted the visa on 26 May 1962. In recognition of his struggle, he was granted the visa free of any charge. On a visit I made to the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg a little over two years ago, I was able to take a shot of that visa, and it caught my attention that the reason mentioned thereon for granting it was “political”, which shows Sudanese authorities’ respectful acknowledgement of the political role Mandela was playing.

Mandela arrived in Khartoum on 19 June 1962 and spent almost 10 full days there. When reading Mandela’s Sudan diaries, we find that the day following his arrival, he met with the Director of the Political Affairs Department at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Osman al-Awad, and later on the same day, he met the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Ahmed Khair. In the evening of the same day, Mandela met with Mohamed Talaat Farid, Minister of Information, Labour, Youth and Sports. One may wonder what this ministry had to do with a visit of a political nature, anyway.

The reason, however, is that that ministry was hosting a few ANC youth as part of a training programme that also took them to Tanganyika and Cuba. Mandela spent a whole week with them in Khartoum, in which he briefed them on the political developments back home, and got feedback about their training in Sudan. For most of those “Bloemfontein boys”, Khartoum was the first place to meet Mandela in person. Among those youths was Dr Mochubela “Wesi” Seekoe, who later served as South Africa’s ambassador to Russia and also held the position of Chairperson of the South African Nuclear Energy Corporation board and Head of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s recommendation structure.

Others also held high-level public positions in South Africa after the end of the apartheid regime. The experience of those youth, including their days in Khartoum, was documented in a movie directed by a grandson of one of these young men, titled “Twelve Disciples of Nelson Mandela” in which filmmaker Thomas Allen Harris focuses on his stepfather, Benjamin Pule Leinaeng.

A notable feature of Mandela’s visit to Khartoum was his meeting with the former President Ibrahim Abboud on 25 June 1962. Mandela wrote in his diary about the meeting, saying: “We meet General Abboud, the President of Sudan. He is extremely cordial, and pledged full support to the African people in their struggle for freedom.”

Against the backdrop of this full support, which included political and financial assistance, the Sudanese authorities granted him a diplomatic passport as a symbolic gesture of recognition and appreciation for his struggle. This passport was distinguished by two things; first, it was a diplomatic passport that represents the highest category among the travel documents granted by states, and secondly, it was the first passport to bear the real name of the freedom fighter that used, up to that moment, a passport under an alias. Mandela had to wait until 1990, after his release from imprisonment, to obtain a passport from his home country.

In a celebration of Mandela Day in Sudan in 2015, the ambassador of South Africa to Sudan, Francis Moloi, highlighted that gesture by saying: “Mandela had been issued a Sudanese Passport in recognition of his stature in the collective conscience and psyche of the people of Sudan.”

At the opening speech of his trial in the Pretoria Supreme Court in 1964, which is considered to be one of the two most significant political statements that Mandela had made during his long struggle, he not only summarised the most prominent milestones of his struggle until that moment, but also praised some African leaders who supported the political and revolutionary struggle of the blacks in South Africa. President Abboud of Sudan gained a rightfully deserved place in that historic statement. DM

Ammar Mohammed Mahmoud is a Sudanese career diplomat currently serving as Counsellor at Sudan’s Permanent Mission to the United Nations in New York. The opinions in this article are his own.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider