Africa, South Africa

Letter to the Editor: Help SA to lead Africa in the management of human mobility

Conspicuously missing in Prof Achille Mbembe’s article is the question on whether the solution to the management of human mobility could be found in addressing the root causes of the out-of-hand exodus of people from their native birth countries to other territories. By Lwandiso Mpepho.

I must forthrightly declare that this is neither a diatribe nor a critique of the esteemed Prof Mbembe and his article. (“Scrap borders that divide Africa”, Mail & Guardian, March 17, 2017.) It is however an attempt to take the discussion forward on the issue of human mobility in the African context. Mbembe writes that “the government of human mobility might well be the most important problem to confront the world during the first half of the 21st century”. There is nothing intrinsically objectionable to this assertion as it is normative and open to interrogation.

The article aptly captures the intricate issues in the management of human mobility, inter alia, “rights of non-citizens to cross national borders; externalisation, militarisation and miniaturisation of borders; increased procedures and identity verification at ports of entry; violence directed to non-citizens; anti-immigrant racism; politics of sovereignty, geopolitics’, etc. It advances a call that South Africa should lead Africa’s efforts to “grant mobility to all her people and reshape the terms of membership in a political and cultural ensemble that is not confined to the nation-state”. According to Mbembe there is “no country better placed to take the lead on this question than South Africa”.

Mbembe, perhaps owing to limitations of space in the publication, doesn’t go further to explain how South Africa ought to discharge this envisaged role to lead Africa “to grant all her people mobility in terms not confined to the nation-state”. Right at the turn of the 21st century the democratic South Africa articulated its position in relation to human mobility in, among other sources, paragraph (h) of the preamble of the Immigration Act No. 13 of 2002 of the Republic of South Africa, that, “the act aims at putting in place immigration control measures that ensure that the South African economy may have access at all times to the full measure of needed contributions by foreigners”. The operative phrase is the “full measure of needed (economic) contributions by foreigners”.

Mbembe’s call stimulates numerous questions such as how should South Africa lead Africa to grant mobility to her people? What would be the rights and responsibilities of the leader and the led? In other words, the thinking process ought to equally prioritise practical matters on how to deal with known and unknown challenges related to the removal of borders. At the current juncture, South Africa seems to be fending for itself in finding panaceas to its domestic challenges emanating from the porousness of its borders, from fighting all sorts of crimes involving foreign nationals to attacks on foreign nationals by citizens. This raises a question – where is Africa to help South Africa assume its honorary (as proposed by Mbembe) role to grant all Africans mobility not confined to the nation-state?

Conspicuously missing in Mbembe’s article is the question on whether the solution to the management of human mobility could be found in, first and foremost, addressing the root causes of the out-of-hand exodus of people from their native birth countries to other territories. In relation to this point, Joseph H. Carens, in his book The Ethics of Immigration, argues that there are three interrelated reasons that give rise to one of the variants of human mobility, refugees. Carens mentions these as “causal connections, humanitarian concern and the normative presuppositions of the state system”. The first relates to the actions of some states to stimulate the movement from one’s birthplace to another. The second is about the need for a safe place to live and the last one deals with limitations and failures of the state system to serve its people.

It is a recorded fact that pre-1994 the Europeans dominated immigration to South Africa but this trend disintegrated with the demise of apartheid and the country opened up to nationals from other continents and countries. The increase in the movement of people across South Africa’s ports of entry post-1994, coupled with the increase in the number of its trading partners, presented a number of costs and benefits for the country. In relation to the costs, the country has had to jerk up its border management capacity and mechanisms in terms of infrastructure and personnel. On the benefit side, the country has diversified its trading partners and more products are traded with the rest of the world.

Add to the above mix refugees who came from the neighbouring and far-flung countries, particularly on the continent. This situation has created all sorts of domestic challenges that South Africa has now to confront. When it worked to the benefit of those moving to South Africa, the country was hailed as a leader in many respects in Africa and now that the state system seems to be unable to cope with the challenges emanating from the ever-increasing number of people from all over Africa and elsewhere, irrespective of whether or not they make any needed economic contribution, South Africa and her citizens are given all sorts of offensive labels.

Therefore, the key question is: are there any African states willing, able and offering their expertise and resources to work with South Africa to address the challenges Prof Mbembe raised in his article? The contribution of the likes of Prof Mbembe as African intellectuals in South Africa is greatly welcomed but is inadequate to help South Africa assume its honorary role to lead Africa in the management of human mobility. African intellectuals in South Africa ought to be supported not only by their governments but by all actors in addressing the management of human mobility in Africa. DM

Lwandiso Mpepho is an International Relations scholar and South African diplomat.

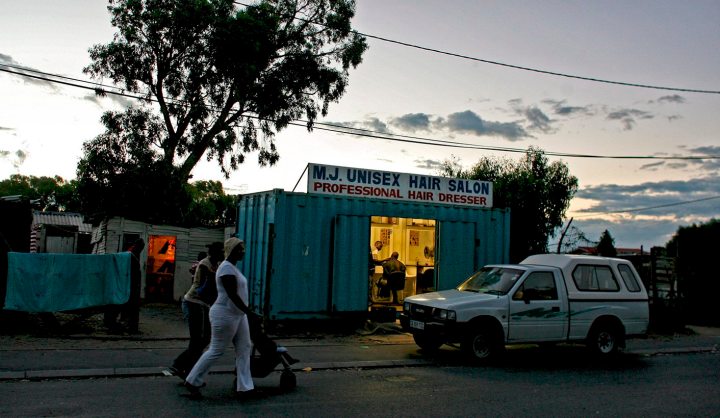

Photo: Picture dated 13 February 2008 shows South African pedestrians walking past M.J Unisex Hair Salon run out of a transformed shipping container by Hair Dressers from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) in Masiphumelele township in Cape Town, South Africa. EPA/NIC BOTHMA