South Africa

Jacques Pauw on Vlakplaas’ Apartheid assassin, Dirk Coetzee

Dirk Coetzee was the Apartheid's henchman, but also the man who told the unvarnished truth about the death squads. MANDY DE WAAL speaks to Jacques Pauw, the investigative journalist who broke the story about SA’s Apartheid death squads in the now-defunct Vrye Weekblad.

One of the most terrifying truths to emerge after Apartheid died was the story of Vlakplaas, a farm some 20 kilometres outside of Pretoria that served as the headquarters for a South African police death squad headed by Dirk Coetzee.

In his book Into the Heart of Darkness – Confessions of Apartheid’s Assassins, investigative journalist and author Jacques Pauw relays how Apartheid death squads each had their own special way of making bodies disappear. “Coetzee burnt the bodies to ashes on a fire of wood and tyres,” Pauw writes in his book.

But it is the manner in which this was done that made parents whose activist children were murdered, shake from haunting sobs at South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings. “They braaied my son while they drank and laughed,” one tortured mother told the amnesty-granting restorative justice system, which was set up to deal with Apartheid crimes.

In his book Pauw describes how ANC operative Vuyani Mavuso met his end at the hands of Coetzee and his team of assassins. First Coetzee tried to poison Muvaso, but when that didn’t work, the man was tortured for hours. “Mavuso must have known by then that he was going to die at the hands of his captors. Yet he never spoke or pleaded for mercy,” Pauw writes.

On the banks of the Komati River, near the Mozambique border, ‘knock-out drops’ were administered to Mavuso and it was only then that he fell unconscious. A policeman stood on the operative’s neck and then pulled the trigger of a Makorov at close range. The operative was dead.

“In a dry ditch on the slightly elevated river bank, a shallow grave was dug with bushveld wood and tyres. The two corpses (Mavuso was murdered along with an askari called Peter Dlamini) were lifted onto the pyre and as the sun set over the Eastern Transvaal bushveld, two fires were lit, one to burn the bodies to ashes, the other for the security policemen to sit around, drinking and grilling meat,” Pauw writes in the book.

Dirk Coetzee told Pauw during the eighties: “Well, during the time we were drinking heavily, all of us, always, every day. It was just another job to be done. In the beginning it smells like a meat braai, in the end like the burning of bones. It takes about seven to nine hours to burn the bodies to ashes. We would have our own little braai and just keep on drinking.”

“Coetzee was never driven by remorse at all, and it is important to note that. There was no remorse for the people he had killed. In fact, Coetzee’s best years were at Vlakplaas. It was the highlight of his life,” Pauw tells Daily Maverick in a phone interview a day after Coetzee’s death from kidney failure.

“Dirk Coetzee always said to me that if he had stayed at Vlakplaas he would have killed more people than Eugene de Kock. There was no remorse,” Pauw says. Like Coetzee, Eugene de Kock was a ruthless killer for the Apartheid regime, earning the moniker ‘Prime Evil’. (De Kock took over the running of Vlakplaas after Coetzee was ousted in the early eighties.)

Later a disgruntled Coetzee would tell all about Vlakplaas and SA’s death squads, and Pauw would have the story that would launch his career. “I was very young when I first started to speak to Dirk Coetzee. I was 25 or even younger,” Pauw says of those first meetings with SA’s Apartheid assassin.

“I probably just listened to this man with my mouth wide open because I came from a fairly protected background in Pretoria with a headmaster as a father, and things like that. I remember thinking that I must string this man along for as long as possible – give him more booze and what have you so that I could get this story,” the investigative journalist says.

“Dirk Coetzee was very engaging and friendly, and he laughed a lot. But I have long learnt that people like Coetzee and De Kock don’t come with horns. The irony is that Coetzee and De Kock are like two peas in a pod. The one started Vlakplaas, and the other took it over. But they have completely different personalities.

“De Kock is a sour and sullen character, while Coetzee was very open and engaging. If you look at the two, Coetzee was clever enough to confess and make a deal. De Kock is silent and won’t talk, and look at what happened to the two in the end,” Pauw tells Daily Maverick. Coetzee and De Kock became sworn enemies after the founder of Vlakplaas revealed the existence of SA’s death squads. De Kock disclosed his crimes to the TRC, but wasn’t granted amnesty. In 1996 ‘Prime Evil’ was found guilty of 89 charges, including six of murder and two of conspiracy. He is currently incarcerated in Pretoria Central Prison.

Coetzee came clean seven years before De Kock. But how did Pauw and Coetzee get to meet? “When Dirk Coetzee was the commander at Vlakplaas, and now we are now talking about the early eighties, he was supposed to kidnap an ANC man from Swaziland. He botched the kidnapping and it became a diplomatic embarrassment for the SA government. Johan Coetzee was then the head of the security police and he transferred Dirk Coetzee to the dog unit. I remember that Dirk always said that he landed at the dog unit without a dog,” says Pauw.

Later, when Coetzee’s police career ended, and he started hanging out with a man being investigated for corruption and extortion, the Vlakplaas founder’s phone was tapped. Coetzee compiled a report about illegal phone tapping that the former death squad leader handed to Van Zyl Slabbert, who was a member of the opposition in Parliament at the time.

“That is how I first got to hear about Dirk Coetzee. My colleague Martin Welz (the editor of Noseweek) and I went to go and see Coetzee, and he started talking. By 1985 he was telling everyone about Vlakplaas. But no one would listen to him, no one wanted to believe Coetzee – God knows why. I think we got the Vlakplaas story because we were prepared to listen to him. As we started listening to him, he gave us more and more information,” Pauw says.

The young investigative journalist would meet with Coetzee and speak to him, then leave and cross check what the Vlakplaas founder had told him. “I would check out what he had told me by cross referencing the information with newspaper articles. I got hold of the inquest into the death of Griffiths Mxenge, and every time it was exactly as Dirk Coetzee had told me, so it was very clear that he was telling the truth.”

This was South Africa in the eighties, a period when anti-Apartheid activists were dying and nobody was ever arrested for their deaths. “Back then, of course, it wasn’t the kind of story that the mainstream newspapers would publish because there was a state of emergency. It was literally only when Vrye Weekblad was started that Max (du Preez) and myself decided that we had to publish the story,” Pauw says.

Vrye Weekblad was the legendary anti-Apartheid weekly Afrikaans newspaper formed by Du Preez, Pauw, a handful of hard-nosed journalists and a nervous banker in 1988. The Vlakplaas story was published in 1989, but only after Coetzee had been taken out of the country by the ANC, who gave him sanctuary on the condition that he told the truth about Vlakplaas. This project was managed by the ANC’s chief of police, Jacob Zuma.

“There was a time in the early nineties when I thought that Coetzee’s interaction with the ANC had really made a difference to him. He was talking…” Pauw breaks the conversation with a small chuckle. “It was very funny. Remember that he was never trusted by the ANC who were merely doing their part of a deal. It was not as if they ever liked Coetzee,” says Pauw.

“After Coetzee had spent some time with the ANC, he would speak a real ANC-type language. He would use all the phrases, calling the ANC people comrades and that sort of thing. After he came back to South Africa in the mid-nineties, he was very disillusioned because he believed in his own mad mind that he was going to become commissioner of police. He also said that this was something that Jacob Zuma promised him, but I really just can’t see it,” Pauw adds.

“Instead of becoming a commissioner or a very senior policeman, the ANC shipped him off to the national intelligence agency where he sat in the archives reading newspapers. He became very bitter again, this time against the ANC, because he thought that he had been shafted again,” he says.

“The last time I spoke to him, which was August last year, he was very bitter. He only had twenty percent of his kidney function. He said to me that he was finished. I think he died a very unhappy and very bitter man.”

How did Pauw react when he heard Coetzee had died? “I am not going to mourn Dirk Coetzee, but I sat down when I heard it and thought about the times we had together. To a certain extent he launched my career. I will be forever grateful to Coetzee for never lying to me. There wasn’t anything he told us that wasn’t true, and for that I will always respect him,” says Pauw.

The investigative journalist and author tells people that while it is easy to condemn Coetzee for who he was, the Apartheid assassin should also be recognised. “We need to acknowledge him for the role he played in bringing out the truth. If it wasn’t for Coetzee, De Kock would never have been exposed and a lot of activities would never have been revealed. In that sense we should acknowledge him.”

Dirk Coetzee was a man who told the terrible truth about SA’s death squads. But he was also the mastermind who helped create them and who set up Vlakplaas. As Coetzee himself told Pauw in the late eighties:

“I was the commander of the South African Police death squad. I was in the heart of the whore.” DM

Read more:

- Vlakplaas and the murder of Griffiths Mxenge by Dirk Coetzee from The Hidden Hand: Covert Operations in South Africa, edited by Anthony Minnaar, Ian Liebenberg, and Charl Schutte.

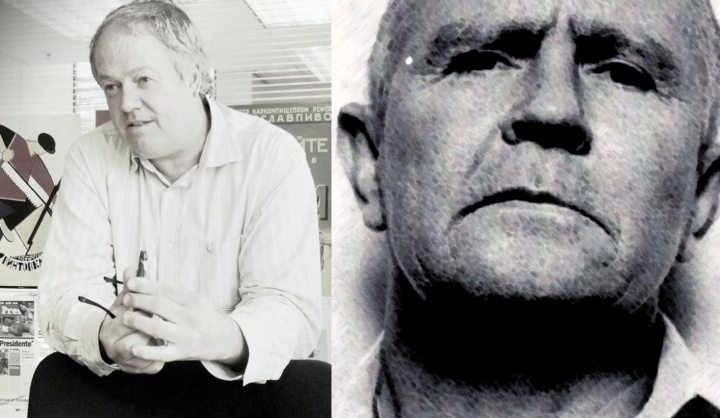

Photo: Jacques Paw, Dirk Coetzee

Become an Insider

Become an Insider