I recently had cause to reflect on the act of writing that drives me. The act, as I call it, borrowing the title, only, of Arthur Koestler’s “act of creation”, is more meaningful than what I have written, more, even than reading what has been published. Once I have written something, I read and reread to make changes and corrections, and after it has been published I have no desire to read it again.

Of course, with the comments section of online articles, I try to engage readers to establish a relationship – for the sake of the publication. I am loyal in that way. This does not mean I look forward to reading my own work. There is no joy in that. Writing is what I do, and I do the best I can with what has been given to me…

About the reflection I did on this act of writing. Two things happened over the past week or so. First, I had a brief exchange with a few friends about my grammatical choices, and where I may or may not have “gone wrong”. Second, I was meant to give a talk about making academic writing more accessible, more meaningful, and less obscurantist – which I define as different from “obscure”.

I learnt to run before learning to walk

In the first instance, I readily accept that I am not a brilliant writer, at least not in the mould of the great writers who have inspired me over the years. I have to acknowledge, and make the point that I learnt very little English over the first 19 years of my life. More specifically, as people of my generation, who spoke Afrikaans at home and attended Afrikaans schools, our earliest formal education did not include advanced English literature and grammar, and very little “composition” – which I recall, now, that I enjoyed.

In my case, the first significant reading I did was a leap from very poor English education to works translated from French (existentialists), German (nihilists, phenomenologists and philosophers) and Russian writers like Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Leo Tolstoy, Boris Pasternak, Nikolai Gogol and Anton Chekhov.

There is, therefore, a large gap in my grasp and ability to write in English that could have been filled if, as a teenager, I had read Shakespeare, Dickens, Brontë, Chaucer or Virginia Woolf.

I did, nevertheless, get to Woolf at about the same time as I did Simone De Beauvoir, Gustave Flaubert and Albert Camus. I would get to great writers like Salman Rushdie, VS Naipaul, Charles Baudelaire, Gabriel García Márquez, Jorge Luis Borges, Mario Vargas Llosa, and because of my love of photography, Susan Sontag and Roland Barthes only in early adulthood, most in my twenties.

A fitting analogy may be that I got into a Formula 1 car without having a driver’s licence, or being able to drive Trotters Independent Traders’ Robin Reliant (Google that, Floyd™) – which really makes me a rubbish driver… A better analogy would probably be that I learnt to run before I could walk.

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

Economists hidden in thickets of algebra

In the second instance, I have been concerned about the wilful obscurantism and the back-slapping pride of writing by economists who, Joan Robinson argued, avoided responsibility of their role in reproducing the intellectual basis of capitalism’s inequality, and were “wont to excuse the inequality generated by private property in the means of production… [then]… crept off to hide in thickets of algebra” (that is a line from my doctoral dissertation). I have previously written about the “mystification” of economics. See here (2016) and here (2014).

I should add, hastily, that there is nothing exceptional about my efforts to get academics, especially in economics, and public policymakers to make their work more accessible and available for wider consumption.

One problem, especially among economists, is that physics envy makes them think they’re “scientists” – like physicists. Sometimes it forces economists into “economics rationalism” that justifies inequality and discrimination. Ask Laurence Summers, darling of liberal capitalist orthodox… Read more about Summers here, here, here, and how his protection network has helped him here.

Read more in Daily Maverick: “Afrikaans may die – what is significant is whether it will be killed or suffer a ‘natural’ death”

A few years ago, shortly after I resigned as Dean of Business and Economics Science at Nelson Mandela University, where I intended to drive a process of making academic writing more accessible, Paul Romer gave up his senior management position at the World Bank after attempting – and apparently failing – to convince economists and public policymakers to simplify their texts, without losing their value.

Researchers (mostly economists) pushed back, and Romer left the Bank. His departure, and apparent loss in the battle against impenetrable prose and “logic” obscured in thickets of mathematical formalism, exposed a “communication crisis in economics”.

I have come to learn that this push-back is a standard response by orthodox economists (in South Africa, too), by functional and organic intellectuals given to scientism.

Anyway, about the World Bank Romer has said: “DEC [Development Economics Group, the Bank’s research arm] should be the part of the Bank that prevents the entire organisation from using… vague persuasion. But we can be the voice that criticises vague overstatement only if we are consistent in setting and meeting high standards for clarity of our prose and are willing to admit a mistake when we make one.

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

“So, to build trust, the highest priority for the Office of the Chief Economist [that is, Romer] will be to insist that any document that this office produces is written clearly, concisely, and is correct to the best of our knowledge. We may not be able to prevent other units from publishing poorly written documents, but nothing will prevent us from keeping track of the relative strength and weaknesses of all bank publications.”

These passages are not part of my day-to-day work as a columnist and writer. It comes into play on the occasions that I am invited to give a lecture, talk or lead a seminar. Among the myriad lessons I have learnt is that saying something, anything, that makes academics, public policymakers, politicians or public intellectuals uncomfortable can be career-ending. Yet, I write.

Why How I write

In some ways writing comes easy. I have never had writer’s block. I use the same technique to get out of a slump as that which I sometimes tell others. When a student says she suffers writer’s block, I follow a very simple procedure. I ask her to write down that she has writer’s block, and then to write why she thinks she has writer’s block, followed by questions and comments about how one gets out of having writer’s block. The first thing that happens is that the student actually starts writing. That is the aim, innit? It is how I write. I sit down and write.

Writing can also be fun. More so if you are free to express yourself. Like most writers would admit, I almost always need an editor to clean up my work and prevent any legal or other challenges. As with grammatical or typographical errors, I don’t always get things right. Sometimes I may contradict myself, sometimes I have to correct earlier comments, statements or claims.

Among the many weaknesses in my writing is that I often use dead or useless phrases that make no contribution to a sentence. I often also use a passive voice, a hill I will die on. This is philosophical and historical.

Read more in Daily Maverick: “SA has poisoned my brain, my mind and the ubiquitous tourist brochure conspires against me”

For instance, it is always necessary – in my mind it is – to avoid making absolute claims, or leaving no room for errors or irrationalities – even if you know something to be true. It is especially important that when you make a factual statement, to provide evidence – so your best bet is to be cautious. This approach tends to clutter texts with words and phrases like “perhaps” or “it seems like,” “apparently” or “evidence suggests”… I make no excuses for using any of those.

As for grammatical errors, I would admit to them and where I think it necessary I would change or correct myself. I also know, however, that language is dynamic with pronounced regional differences. For instance, Estuary English is significantly different to Geordie – and English spoken in Singapore, Jamaica or Kolkata is a world away from that which is spoken in the Home Counties.

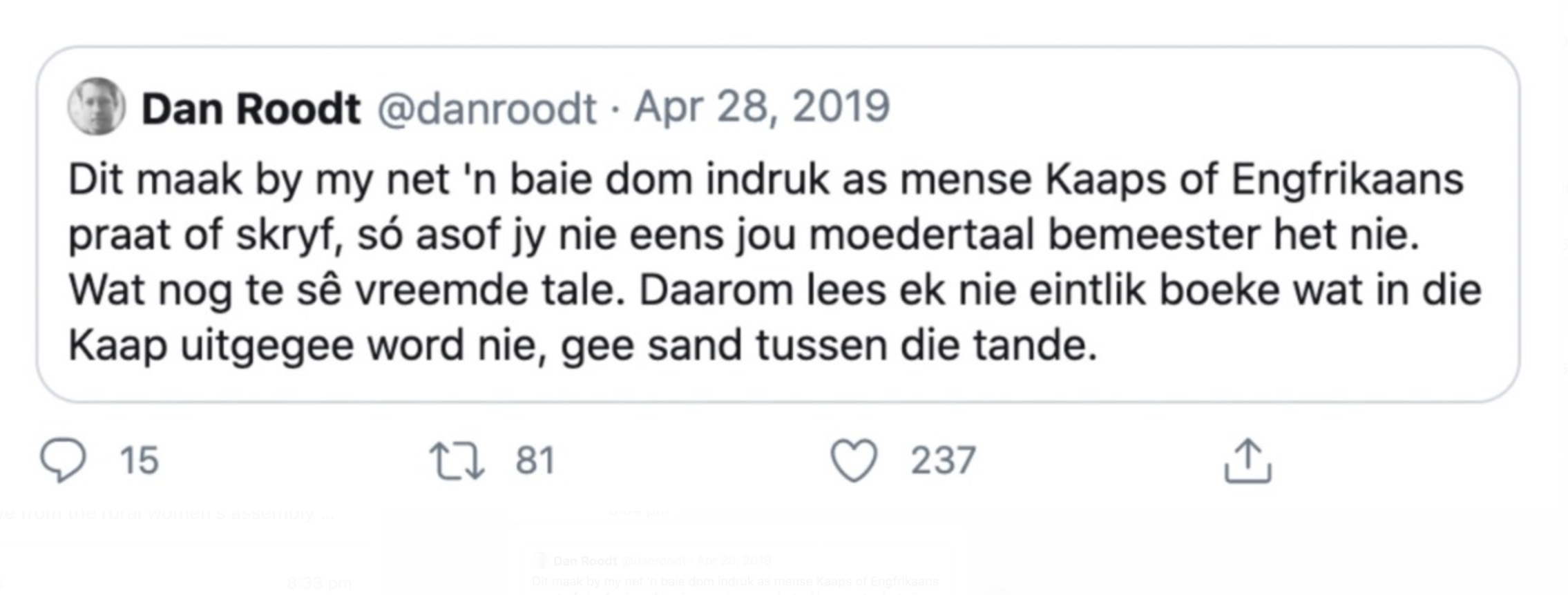

Similarly, the Afrikaans I spoke in Johannesburg’s southwestern townships is also different from the way it is spoken (among fellow coloured people) in Cape Town, and also from Afrikaans spoken among (white) Afrikaners in Pretoria – never mind searches for purity or exceptionalism. See, for instance, this pic of a tweet by Dan Roodt.

Finally, the very basis of writing is to take an idea from the writer’s head (or something from her notebooks or recording), place it on paper, and into the mind of the reader, intact. This is not always simple, nor is it easy.

Because I enjoy writing, I can be accused – as I have been – of overthinking and, as a friend pointed out this week, of making grammatical errors. I’m not proud. I have no problem with being corrected. It really is okay to be wrong. I also enjoy being wrong or not knowing.

One of my favourite thinkers of the past century, the late great physicist Richard Feynman, once said: If you don’t make mistakes, you’re doing it wrong. If you don’t correct those mistakes, you’re doing it really wrong.

Now where was I? Oh bugger that, let me leave you hanging.

P.S. One of the many reasons I miss my late friend Ivor Sarakinsky was because he often caught obscure references to songs by Steely Dan, Frank Zappa or Tom Waits in columns I write. As mentioned, writing can be fun. DM

Love it! Thanks Ismail. Your piece gently declares, ‘Refining the human spirit requires editing of self’.

hahah, thanks Philip. I will live to be 150 and will take pride in needing an editor, and in my own limitations.

Brilliant Ismail – yours is the only piece I read religiously ‘cause there are hidden gems in there, guaranteed. Strength to your arm!

I teach first-year economics. My students learn in their first class that understanding the concepts, how they relate to each other, and their real-world applications, are our priorities. Mathematical description, while important, only follows. The result is that most of them end up much better at writing about economics than is usual.

Ah yes, Dan Roodt. That bastion of supremacy, legitimacy and all things sacrosanct.

Not.

Great read – and may I say very well written!