The opposing views tested by lockdown

Remember the world before coronavirus and its initial lockdown: when Monday was the worst day of the week and Friday the best, precisely because it was opposite of Monday? In those pre-coronavirus days, work was the suspension of life for most people. Friday heralded two-days of work-free emancipation while Monday was the unwelcome beginning of five days of work-enforced lockdown. Challenging this orientation is another conception of work; one that sees the ability to express ourselves through our work – our creative labour – as an essential part of what it means to be human.

Might lockdown provide any answers to these opposing positions?

Another standard idea about what makes us human is that we are essentially free-born individuals who, for pragmatic reasons, choose to come and stay together in a “social contract”, as argued most prominently by Thomas Hobbs in the 17th Century, with further elaborations by Jean-Jacques Rousseau in the 18th. This is the very contract President Cyril Ramaphosa is urging us to heed by putting away our individual differences in order to beat coronavirus through united, collective action. Against this contract and the tensions inherent in the conflict between natural-born free individuals who choose to forsake their unbounded liberties for the protections of liberty-restricting society, there are others who say that society is much more than a contract of convenience. For them, society is no less than an essential precondition for our very existence as individuals. “Ubuntu” is a poetic expression of this idea.

The emerging answers

Lockdown provides us with limited, though unprecedented laboratory-like conditions, to test these various ideas. What answers might be emerging from these first-ever, real-life test conditions?

Lockdown offers a unique microscope into the nature of our relationship with work: is it a chain or an expression of our liberty? For the first time ever, 1.7 billion people have been prevented from normal work, with several hundred million not being able to work at all. Large numbers around the world nonetheless still – or, initially – receive full pay or a substantial part of their normal income. For these many millions, this was like being in Cockaigne. Cockaigne was a mythical place of dreams in medieval Europe where the harshness of peasant existence was softened by the idea of a land of plenty: a place in which toil was unknown, food was plentiful, and skies rained cheese. The name of this heavenly place changed from country to country, but the idea beckoned regardless of name.

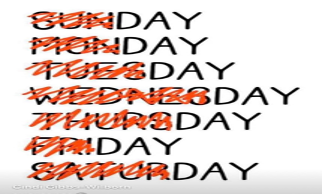

Alas for the dream. Lockdown has turned Cockaigne into a nightmare. This reality needs no elaboration. Cartoons helped by making us laugh at the nightmare. This is one of the many going the rounds within the first few weeks of what ought to have been the bliss of endless Fridays.

As a limitation to the experiment, it might be objected that being confined to one’s home during the hard lockdown severely curtailed the normal activities of work-free weekends. However, I suspect few people have not experienced the challenge of how to kill excess time, with serious boredom being a problem, particularly for children.

The absence of social interaction is another limitation of lockdown’s ability to test whether or not work – productive labour – is, for some, an unexpected human need. Being with other people, which, for most of us, was a normal part of pre-coronavirus weekend activities, have been denied or seriously curtailed by lockdown. However, it is this very limitation to the lockdown experiment that speaks to other people being an essential need; a need that lockdown has now demonstrated beyond question.

I had the good fortune of walking the back streets of Cape Town’s Wynberg on the first day we were allowed out of our homes for purposes of exercise. The streets were full of people of all ages, shapes and sizes, along with prams and dogs, all celebrating this now valued freedom of movement. Still more telling was that (virtually) everyone took unmistaken pleasure in greeting everyone else. Our social being was being affirmed and enjoyed and we were rejoicing in our togetherness.

The pain of social isolation speaks to us through the numbing numbers of lockdown-related instances of gender-based violence, suicides, and other cries of psychological distress.

Society, this is to say, is considerably more than just a contract of convenience, chosen on a cost-benefit calculation.

Society makes us human

But what is this “something” more? Where does it come from, if not our genes? Where do individuals fit in? Is society no more than an amalgam of individuals and their families, which is Margaret Thatcher’s answer. Or, by contrast, is the answer the one provided by those Marxists who say that society is everything? Moreover, what, if any, connection is there between this lockdown-lesson on the importance of other people and the previous one about work?

“Human nature”, even when not a bald assertion, provides no answers, or, no sufficient answers. This forces us to explore elsewhere why we have a need to work, over and above the fact that for most people life occupies the space in between work. Or, more particularly, why we need the affirmations that come from productive labour being an expression of self, as I shall be arguing. We similarly need to look elsewhere than a science-free, ill-defined “human nature” for why we are unavoidably social beings. This question includes the features of the relationship between society and the individual and, ultimately, of the implications of that relationship.

This “somewhere” else, where we need to look for answers, is… ourselves. Our consciousness is, in my view, the most important of the characteristics that make us human, make us different from all other species. The very name we give ourselves – homo sapiens – affirms this. Although we often have good reason to question our sapiens – our wisdom – our sapiens attests more modestly to the fact of our consciousness rather than the way in which we frequently abuse it. Let us additionally remember – because we are so quick to forget in this age of divisive identities – that it is species-defining consciousness. This is to say, it applies to all of us, everywhere, since the first emergence of our species some 200,000 years ago (although the specificities of the form constantly change, according to the particularities of time and place).

Yet, notwithstanding the fundamental importance of our consciousness, we are not born with this species-defining endowment. Psychology and the brain sciences have firmly established that consciousness has to be acquired, with interactions with other people being essential for its emergence, growth and lifelong development. The most enduring features of this nurturing occur during the years of our total dependency on others for the continuation of our very lives. Our consciousness is the child of the materialism of the milk, food, water, warmth, shelter, caring and general support given each one of us by our interactions with the providers of these basics, essential for our survival. Our sense of fairness, including right and wrong, along with the need for meaning in our lives are additional seeds of these early years.

Beyond this, science can’t (yet) say much more about consciousness. Science knows nothing notable about its anatomy and physiology. But we do know one thing of fundamental importance: its location. We don’t know where – or even if it has a fixed place – but we do know that, provided it has been nurtured into existence, it is integral to a living brain and dies with the death of the brain. This knowledge opens so many doors. Despite its many and enduring mysteries, being a feature of the brain means that consciousness is not a metaphysical something but material just like the brain itself. But it is matter unique to itself.

Unlike the mechanistic materialists of the mid-18th Century who extended to people the 17th Century idea of animals being machines – or to its contemporary form of people being sophisticated computers – consciousness is matter conscious of itself. No less importantly, it is conscious matter in constant interaction with both the internal and external environments and experiences of each of us, its individual bearers. This makes consciousness both subject and object, both active and passive, both determined and determining, both receiving of information and sender of information in a loop that ends only with death (or prior loss of consciousness).

The specificities of how all this acts on the various other characteristics of our species – thought, language, labour, love, empathy and so on – remain much more as questions rather than as scientific answers rooted in the materialism of both our being and our consciousness.

Consciousness unlocks an understanding of the emerging answers

What does it say about labour and the nature of work? For our limited purposes, my suggested answer is two-fold.

First, the consciousness of the people lockdown prevented from working is a consciousness of its time. In other words, it is a consciousness in need of the stimulations and distractions of the environment and experiences of the 21st Century, which it bears. Trade union struggles, along with the productivity of today’s economy, provide leisure time unthinkable when workdays meant 16 hours and the work week was six days long, at least. Moreover, electric lighting has greatly extended the non-working time available, as has central heating for people in the northern hemisphere. Boredom comes with being housebound in the 21st Century and all the more so when there’s no live sport, and alcohol is no longer for sale. Unlike the expectations of earlier times, the enlarged consciousness of the 21st Century becomes the burden of boredom in the absence of the package of accustomed external stimuli, mainly entertainments.

The internal stimuli are the second part of my answer. We all have them even though they await a different environment and range of experiences for their proper enrichment. Labour, as a self-expression, becomes a need made by the origins of our consciousness, as further shaped by the particularities of the social environment of the day. Contemporary society is not a propitious environment. Labour as a self-expression is still borne for most workers and, constrained, for the rest of us, by the hostile competitiveness which, allowing for only a few “winners”, discards everyone else as a “loser”. But the need for self-expression remains intact, despite these social realities. Stripped to its quintessence the need to express ourselves through our self-activity, our labour, lies in the reassurance we need as soon as we recognise – that is, become conscious of – our initial, utter dependence on our caregivers. Pleasing them is all important as our nourishment, health, security, and comfort lies in their hands. Affirmation of what we do is, for the rest of our lives, part of this reassurance. Thus, it matters little who gives this affirmation; reassurance from whatever source and for whatever reason is what is craved.

Our need to re-create the society that creates us

Speaking on Youth Day, 16 June, President Ramaphosa noted:

“Covid-19 is pregnant with opportunities. So, I’m throwing a challenge to young people… post-Covid-19 is a new platform and we need to set up different ways of running our economy, ownership… and even the production of our economy.”

He could make this challenge because consciousness, born of social living, allows us to use our reflections on our social life to imagine a greater harmony between the society that shapes us as individuals and our needs required for maximising our fulfilment as individuals. This enables us to extend the Judeo-Christian idea of God having created us in his own image, into us creating the idea of a society in the image of a nurturing humanity.

The laboratory so unexpectedly provided by lockdown is providing us with clues to some of the needs created by the characteristics that define our species. Ubuntu – the knowledge that people are people because of other people – is poised with the possibilities of our consciousness reshaping the society that creates our consciousness, which then shapes so much of us according to the specificities of the material conditions of our time and place as social individuals.

In 1844, a 26-year-old German refugee in Paris, reflecting on the material conditions of his social world and of the form some of them took in the prevailing consciousness of the time, wrote:

“Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. … To call on them [‘the people’]to give up their illusions about their condition is to call on them to give up a condition that requires illusions.”

The need to better understand those conditions in order to change them persuaded Karl Marx, the young German refugee, to become a Marxist.

The lessons of the lockdown-laboratory would not have surprised him. Indeed, they are seeded within the fruits of his labours. For that matter, so, too, is the fact of Covid-19. The global drive for profit maximisation, for raw materials and the cheapest possible labour has opened some of the remotest parts of the world. The extraordinary complex of corporate supply chains connects these “various production zones, primarily in the Global South, with the apex of world consumption, finance, and [capital] accumulation, primarily in the Global North”. It is these supply chains that provide the vectors for coronavirus, as Don Pinnock and Tiara Walters first reported in Daily Maverick on 7 February, 2020.

We have the knowledge. Rather than being mocked by our sapiens, let’s use our precious wisdom. Coronavirus offers us a rare opportunity to remake the world in our human image. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider