OUTLAW OCEAN PROJECT

The Whistle-blower — an American’s dream job at a shrimp factory in India turns nightmarish

The plant ran day and night, racing against the heat which constantly presented the threat of spoiling. The migrant workers were mostly women, almost exclusively recruited from impoverished corners of the country such as West Bengal.

On 29 October 2023, a 45-year-old American named Joshua Farinella flew into the city of Amalapuram near India’s eastern coast to start his new job as the general manager at a shrimp processing plant. Farinella, who is softly spoken with a shaved head, neatly trimmed beard and full sleeve of tattoos, was excited about the prospect of living abroad for the first time.

True, this would be a high-pressure job, and he would miss Christa, his wife, but he had negotiated a salary of $300,000 a year, more than double what he’d earned at another seafood company in the US. He joked that he was now the best-paid shrimp worker who did not own his company. He figured that if he could stick it out for two or three years he would be set up for life: he looked forward to upgrading his camper van, paying off his car loan and setting aside some money for his stepdaughter’s university education.

Choice Canning’s shrimp processing plant in Amalapuram, India, is on a 3.2ha, walled-in plot, surrounded by rice paddies and coconut trees. (Photo: Ben Blankenship / The Outlaw Ocean Project)

Surrounded by a 2m-high concrete wall, the plant was about 9km northeast of Amalapuram and was surrounded by rice paddies and coconut trees. Security guards patrolled the perimeter, not an uncommon sight at facilities like these. Inside was an eight-acre compound where shrimp, cultivated in nearby ponds, were beheaded, deveined, treated with chemicals that keep them moist, and shipped abroad. In 2023 alone, the plant, leased by a company called Choice Canning, filled frozen food sections at stores such as Walmart, Price Chopper, ShopRite and Hannaford with a little over 8.5 million kilograms of packaged shrimp. (Walmart and Ahold Delhaize, Hannaford’s parent company, said they were looking into the allegations. ShopRite and Price Chopper did not respond to requests for comment.)

During his time in India, Joshua Farinella, a whistle-blower and former general manager of a Choice Canning shrimp processing plant lived in an apartment in Amalapuram, the same town in which the factory is located. Amalapuram is in the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh, where temperatures can reach higher than 48.9 deg C during the summer. (Photo: Ben Blankenship / The Outlaw Ocean Project)

When he arrived at work, Farinella was struck by the number of workers streaming through the gate. It reminded him of an airport terminal, though there always seemed to be more people arriving than leaving. In the days that followed, he came to realise how much labour was required to process shrimp in the quantities demanded by head office — a quota of 40 shipping containers or more than 600 tonnes each month.

Several groups of women walk through a gated entrance to the Choice Canning shrimp processing plant in Amalapuram, India, during a site visit by The Outlaw Ocean Project in February 2024. (Photo: Ben Blankenship / The Outlaw Ocean Project)

On any given day, there might be more than 650 workers at the plant, typically hired by third-party contractors. Hundreds of the workers lived in Andhra Pradesh and went home at the end of each day. The rest were migrant workers who lived at the plant and they served as the backbone of the operation. The plant ran day and night, racing against the heat which constantly presented the threat of spoiling. The migrant workers were mostly women, almost exclusively recruited from impoverished corners of the country such as West Bengal. Many came from the lowest social caste and were illiterate. They slept in spartan dormitories on-site in metal bunk beds. A security guard was usually posted outside near the building’s front door.

At 3am on 11 November 2023, Farinella was woken up at his apartment, which was a short drive from the plant. A manager had sent a WhatsApp message informing him that a woman had been found running through the plant’s water treatment facility at 2.30am.

“She was searching for a way out of here,” the manager wrote matter-of-factly. “Her contractor is not allowing her to go home.” (Later, another manager would explain in a recorded conversation that workers used to escape over the concrete wall, but this had now been fixed “so no one can go out.”). The woman made it as far as the main gate, but was turned back by guards.

In January 2024, Joshua Farinella, a whistle-blower and former general manager of a Choice Canning plant in Amalapuram, India, stumbled on to a hidden dormitory. Inside, Farinella said he found migrant workers sleeping on mattresses laid out on the floor, many without pillows or bedding. (Photo: Joshua Farinella / The Outlaw Ocean Project)

A uniformed security guard stationed outside the workers’ dormitories at a Choice Canning shrimp processing plant in Amalapuram, India, in February 2024. (Photo: Ben Blankenship / The Outlaw Ocean Project)

Forbidding workers to leave their plants when they choose to is a violation of the Indian Constitution and also likely violates the country’s penal code, according to the Corporate Accountability Lab, an advocacy and research group.

Alarm bell

In a recorded conversation, a manager had explained to Farinella that some employees at the plant were allowed out twice a week to shop at the market. There shouldn’t be any reason for them to attempt an escape in the dead of night, Farinella figured. Arriving at the plant several hours later, he tried to get an answer about what had been going on. He was told by a human resources manager that it had all been a misunderstanding. The woman hadn’t wanted to leave after all. An alarm bell went off in Farinella’s mind.

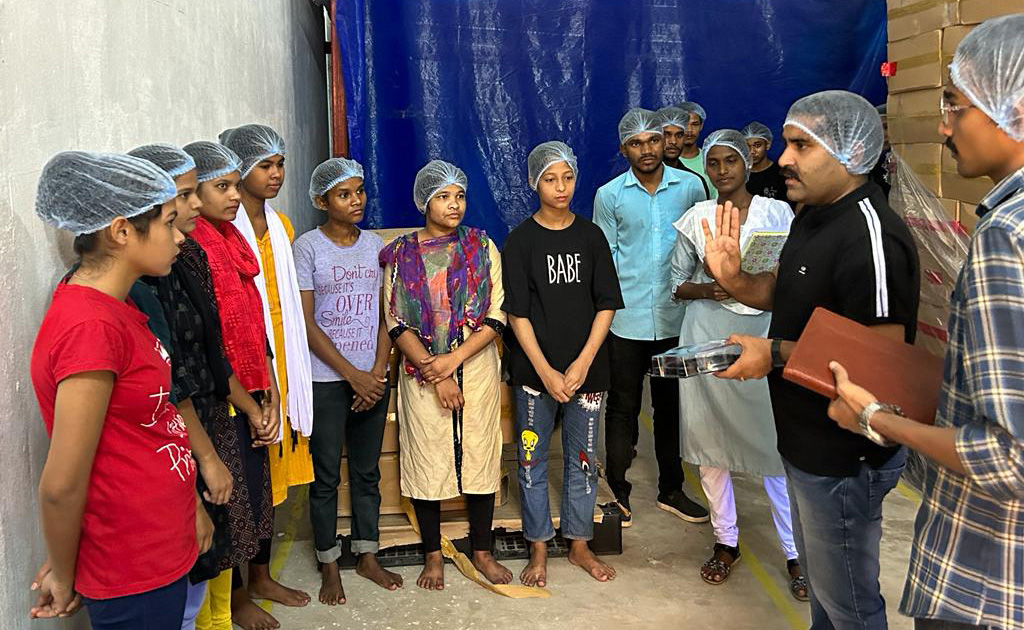

Barefoot workers dressed in T-shirts, jeans and other casual clothing receive directions in a storage area at a Choice Canning shrimp processing plant in Amalapuram, India, in October 2023. (Photo: Provided by Joshua Farinella)

Farinella had worked in the food industry since 2015. Choice Canning made frozen meals in his hometown and had given him a job as a quality-assurance officer in 2015 overseeing food safety rules. He then worked for another seafood company, Lund’s Fisheries, ensuring its supply chain complied with regulations, before returning to his old firm in 2023. He was used to gaps in accounting and flaws in audits. But this seemed much more serious.

Farinella, who was raised in a former mining town in Pennsylvania by a Vietnam veteran and a social security worker, had gone off the rails as a young man, living on the street temporarily and picking up convictions including for drunk driving and trying to cash false cheques. He has since distanced himself from his family; he stopped talking to his parents after they disapproved of him marrying a black woman.

Security camera footage from the Amalapuram plant captured on 12 February, 2024. (Photo: Joshua Farinella / The Outlaw Ocean Project)

Workers covered in red personal protective equipment leaving only their eyes visible stand along an assembly line in a Choice Canning shrimp processing plant in Amalapuram, India. The photo was sent in a WhatsApp group of plant managers in October 2023. (Photo: Provided by Joshua Farinella)

At the plant in India, he would find himself covering up overcrowding on the site by making plans to hide workers when inspectors came around. He found himself misleading customers about the provenance and quality of their shrimp, including its certification status or farm origin, and he said he was told to send off consignments of tainted shrimp to the US. Managers who worked for Choice Canning could be frustratingly evasive, he added, but, at times, they could also be startlingly candid. He captured his dealings with them in secret recordings, screenshots and thousands of pages of documents.

“I have been fighting this from afar for years,” he said, referring to his time in food safety and quality assurance. “Then I find myself right in the middle of it. Not just in the middle of it but it was literally my job to make all of the fucked-up things keep happening.”

***

Americans devour, on average, nearly 3kg of shrimp a year, an amount that has doubled in a generation. In 2001, the crustaceans cost around $25 per kilogram, when average prices peaked, and were regarded as a delicacy. Since then, restaurants and supermarkets have begun to source them overseas and the prices have plummeted. Today, some seafood restaurants offer an “ultimate unlimited shrimp deal” for $25.

In 2015, the hidden costs of cheap prawns were revealed. Reporters found trafficked Burmese migrants, most of them women, held in slave-like conditions in shrimp peeling sheds in Thailand, a country that for much of the previous decade had been the preferred supplier for major Western supermarkets. Some of these food companies cut ties and imports from Thailand dropped.

India helped fill the void, with help from its government which supplied subsidies and loosened laws restricting foreign investment. By 2021, India exported more than $5-billion of shrimp globally and was responsible for nearly a quarter of the world’s shrimp exports. About one in three of the shrimps consumed by Americans today comes from India.

Choice Canning is one of the largest Indian suppliers in the market. It has corporate offices in two big Indian cities, Kochi and Chennai, as well as in Jersey City, New Jersey, and sent shrimp worth more than $80-million to the US in 2023.

In November 2022, the company announced it would be the first Indian company to become a corporate member of the Global Seafood Alliance (GSA), an industry body that promotes responsible practices. Choice Canning sought certification by the Alliance’s monitoring outfit, Best Aquaculture Practices (BAP), which offers to certify every stage of a seafood supplier’s production line. The workplace in Amalapuram carries the stamp of BAP approval. Choice Canning said that shrimp farms that they use do as well. (Presented the findings, the Global Seafood Alliance said they take them seriously and would investigate if they find evidence of violations.)

Antibiotics in the shrimp

Farinella said he was confused to find that when the plant tested for antibiotics in the shrimp, these tests came back positive more often than he had expected. In the US, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) bans the use of pharmaceuticals in shrimp. (The FDA did not respond to a request for comment.)

Much of the shrimp that India produces are raised at small aquaculture farms. The Corporate Accountability Lab, an advocacy group, found in a report released this month that many of these farms rely on antibiotics to protect the shrimp from pathogens.

“If just about everything we pack is BAP and the farms are BAP then how is it that the antibiotics keep coming up?” Farinella wrote to the company’s senior quality assurance manager in a WhatsApp message.

“We never buy shrimp from BAP farms,” the company’s senior quality-assurance manager replied. “All are local, unregistered farms.” The manager, in a jocular aside, told Farinella that “you can imagine the level of documentation skills” required to make it seem otherwise. He added a smiley-face emoji.

How long has this been going on? Farinella asked. “It has always been so,” the manager wrote. “India doesn’t have even 10 percent of the BAP farming capacity it claims. Sad, but that’s the reality!”

The Corporate Accountability Lab report suggests he is right about the extent of the problem. The report says that the Indian shrimp industry is rife with human rights, environmental and safety violations, including instances of forced labour, and that audits by BAP and similar organisations are flawed.

Choice Canning hired a firm, SGS, to conduct daily audits for internal purposes to help police hygienic conditions. These audits often detailed sanitary concerns such as the smell of decay, flies, slime, sludge, lack of ice, broken refrigerators, machines contaminated with algae and fungus, hair and black spots on shrimp, and a spittoon full of chewing tobacco on the factory floor.

An internal audit conducted for Choice Canning by SGS in October 2023 recorded spittoons for pan masala, a digestive aid sometimes containing tobacco, located on the factory floor at the company’s shrimp processing plant in Amalapuram, India. (Document provided by Joshua Farinella)

Annually, auditors from the same firm, SGS, also produced a public-facing audit where the plant was given a clean bill of health. (SGS said they could not share the results of their audits for confidentiality reasons but that they were conducted based on the terms they had with their client.)

Choice Canning also said that documents from Farinella had been manipulated. The Outlaw Ocean Project hired a forensic data firm based in the UK called Signify to review a selection of the most important documents and they concluded that none of the documents they reviewed showed any signs that they had been manipulated.

(Explore selections here from thousands of pages of internal company records, audits, invoices, emails and WhatsApp messages that were provided by the whistle-blower.)

***

“Ship it,” the WhatsApp message read.

This was surprising, even by the standards Farinella had come to expect at Amalapuram. His boss, Jacob Jose, the company’s vice-president of sales and procurement and the son of CEO Jose Thomas, who goes by JT, had just been informed that 225 cases of raw shrimp bound for Aldi South supermarkets in the US had tested positive for antibiotics.

The widespread use of antibiotics in agriculture is causing resistance to the medication needed to treat all sorts of infections to rise across the world. In 2019, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a US government agency, said close to three million antibiotic-resistant infections occur each year in the US, killing tens of thousands.

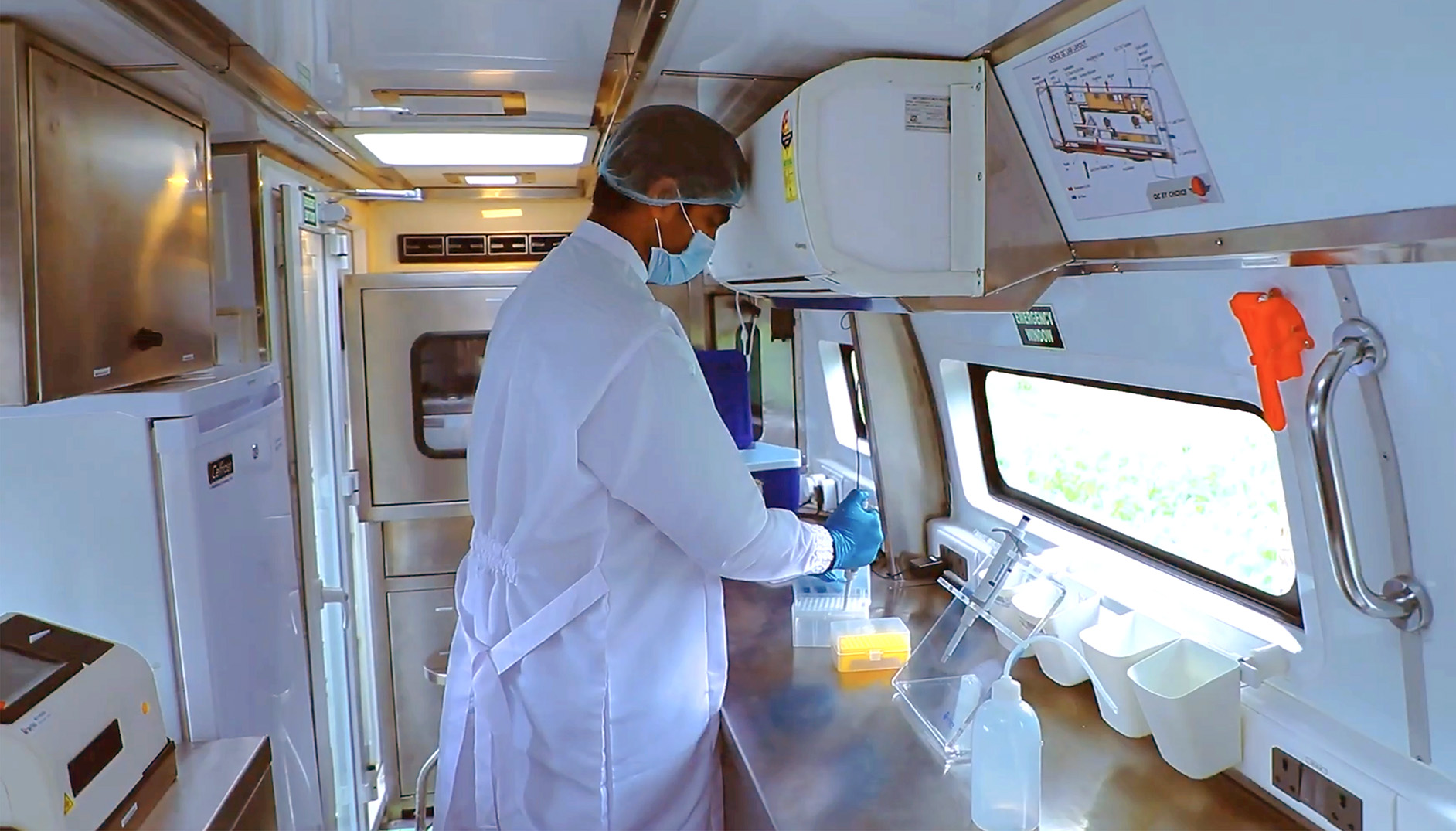

A mobile testing lab used by Choice Canning to test for the presence of antibiotics in shrimp. The lab visits aquaculture farms that produce shrimp for the company, which recently was the focus of allegations about food safety concerns. (Photo: Choice Group)

While the FDA bans importing shrimp treated with antibiotics, the agency only inspects roughly 1% of imported shrimp. By contrast, the EU checks 50% of imported shrimp from India. The chances of any one batch of contaminated shrimp from Choice Canning or other companies being stopped are low, according to researchers.

A company inventory spreadsheet shows that more than 250 tonnes of antibiotic-positive shrimp were received by Choice Canning’s Amalapuram facility in 2023. It is difficult to ascertain exactly how much of this shrimp made it to the US, but company documents seem to show instances when shipments made the full journey. A review of FDA data indicates that the agency has tested shrimp from Choice Canning for antibiotics just 21 times since 2003 and never found a violation. In that same period, the company sent more than 100,000 tonnes of shrimp to the US.

Misleading paperwork

Farinella said that paperwork meant to trace shrimp to certified farms and track the presence of antibiotics was sometimes misleading. The vice-president of Sales & Procurement told him not to use the word “antibiotics” in any internal communications, for example.

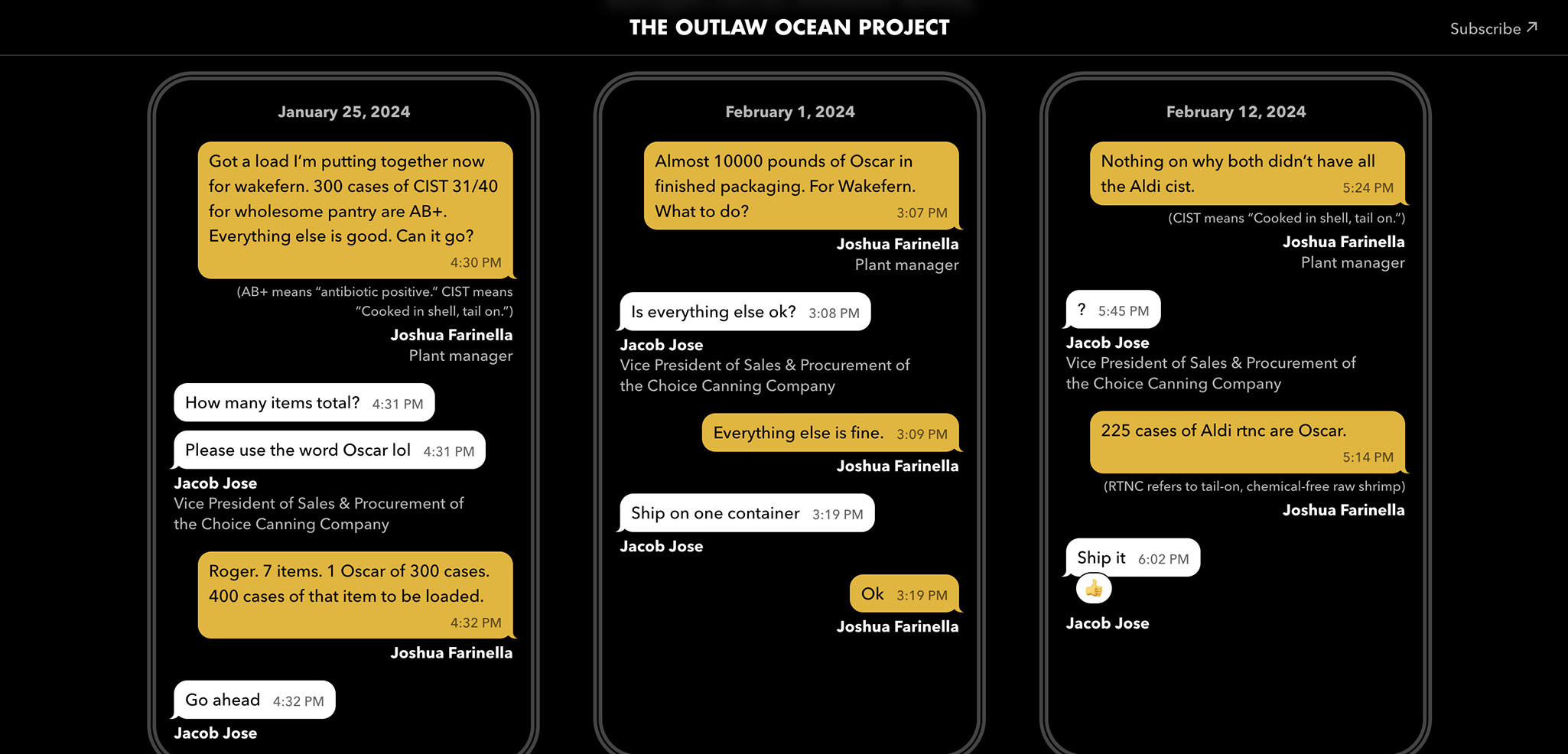

From left: In a message sent on WhatsApp in January 2024, Jacob Jose, Vice President Sales and Procurement at a Choice Canning shrimp processing plant in Amalapuram, India, instructed Joshua Farinella to use the code word ‘Oscar’ instead of antibiotic-positive in internal communications. (Document provided by Joshua Farinella)

“Please use the word Oscar” to refer to shrimp that had tested positive for antibiotics, the manager wrote to him on WhatsApp, adding “lol”. (The company denied ever shipping antibiotic-tainted shrimp to the US and said that this exchange and the meaning of “Oscar” had been misrepresented by Farinella. To see the full response from Choice Canning and from other companies or organisations visit the Discussion Page.)

Farinella said that even though he disagreed with the policy, he did as he was told. “Almost 10,000 pounds of Oscar in finished packaging for Wakefern. What to do?” Farinella wrote on WhatsApp to the company’s vice president for sales on February 1, 2024. “Ship on one container,” the executive texted back. Off it went to the US, packaged in bags marked “all natural.” (Wakefern did not respond to requests for comment.)

***

The Choice Canning site is filled with large concrete buildings that house processing facilities, warehouses, freezers, dormitories, electrical equipment and offices. Clothing is hung out to dry on lines strung between buildings and mattresses are laid out in the sun to air. During his time as the plant manager, Farinella had a wide range of duties: sourcing workers and supplies of shrimp, managing finances, and making sure that the plant hit its monthly production quota.

He struggled at first to establish how many workers lived on site, how they were housed and fed, and how their contracts worked. At one point he stumbled across what he called a “hidden dormitory” located above the ammonia compressors used for refrigeration, putting the workers in danger if there were a leak or a fire.

Mer****, a human resources manager at Choice Canning’s shrimp processing plant in Amalapuram, India, emailed a photo of a mattress that appeared to be covered in bed bugs to Kir****, a human resources executive, in December 2023, alerting him that there was an infestation affecting more than 500 beds at the plant. (Document provided by Joshua Farinella)

In January 2024, Joshua Fairnella, a whistle-blower and former general manager of a Choice Canning plant in Amalapuram, India, and Aja****, a management trainee, discussed over WhatsApp messages a worm found in the breakfast food given to workers at the plant. (Photo: Document provided by Joshua Farinella)

Managers at the plant knew that living conditions for workers needed improving and they conducted regular discussions on WhatsApp and email about how to fix various problems. Once a manager emailed him a photo of bedbugs — part of an infestation that colonised more than 500 mattresses. Farinella found workers sleeping on the floor, using only their shirts as pillows. But he said he and others struggled to get authorisation for the necessary changes.

“We need more bunk beds immediately, this cannot wait for another day please!” the plant’s vice-president of human resources wrote angrily in an email. “Existing people are facing trouble for months.”

Photos taken in January 2024 show toilet stalls outside a men’s dormitory at a Choice Canning shrimp processing plant in Amalapuram, India. The stalls appeared to lack doors and share one communal sink. (Photo: Joshua Farinella / The Outlaw Ocean Project)

A few weeks later, Farinella discovered during a recorded conversation with a labour contractor for Choice Canning that 150 women workers had not had a day off in a year after two employees asked whether they could be released for an outing.

Farinella approved it instantly. He later said that he felt like his “hands were tied” and that he was blamed for anything that went wrong despite not being given the power to change things for the better.

It was also hard, he said, to tell how long employees spent working. A human resources executive admitted candidly in a Zoom meeting recorded by Farinella how she would need to adjust attendance records and timecards to pass an audit.

Minimum wage

State law in Andhra Pradesh stipulates that workers must be paid at least 450 rupees ($5) per day. But an invoice from a labour contractor and a separate email exchange between managers seemed to indicate that some workers were paid only 350 rupees a day. (The company has since said that it always paid the minimum wage to all of its “associates” and recently even gave a raise to some of its staff.)

“It felt dirty,” wrote Farinella later. “I didn’t even want to make eye contact with the workers who were living there or the local workers. I was disgusted and ashamed of everything. I know the workers couldn’t be okay with everything there. And I also knew that every one of them probably thought I was most of or at least part of the problem.”

In December, Farinella asked Jacob Jose if workers could be paid the minimum wage. In an email exchange with senior executives, CEO Thomas declared himself “shocked” that they weren’t already. One of the executives reminded Thomas that he had previously told them “not to make any changes in Amalapuram for the time being,” when it came to wages. (In internal emails, company managers later said they planned to raise the wages.)

***

In January, inspectors from Aldi South, a global supermarket chain, were due to visit Amalapuram to conduct a social audit checking labour conditions at the plant. While some audits are unannounced, Aldi South’s audit was scheduled months in advance. (Aldi South said it was “taking the allegations seriously” and would need more time to investigate.)

Farinella met other supervisors to discuss preparations and recorded the conversation. Managers focused on what to tell auditors about the number of workers at the plant. The size of the workforce is of particular concern during audits, according to the Corporate Accountability Lab report, because auditors want to check the tally of employees at a facility against wage records, available beds, and amount of workspace on the factory floor to see if there are any concerns related to underpayment or safety.

Women work in the kitchen in Choice Canning’s shrimp processing plant in Amalapuram, India, in January 2024, peeling onions by hand. (Photo: Joshua Farinella / The Outlaw Ocean Project)

During a site visit in February 2024 by The Outlaw Ocean Project to a Choice Canning shrimp processing plant in Amalapuram, India, female workers sat together in the canteen eating rice. (Photo: Ben Blankenship / The Outlaw Ocean Project)

The managers also discussed a plan to move the workers offsite to a rented location nearby before the auditors arrived. Labour researchers say that this is not an uncommon practice in dealing with auditors. “We need to show a sizeable number to them,” mused the quality-assurance officer during a recorded meeting in deciding what might be a convincing statistic to tell auditors. Eventually, the managers opted for 415 as a number that would seem plausible.

A few days later, in a recorded meeting, Farinella discussed the plans with a different human-resources executive.

“So basically we’ll call them when the auditor comes in, we’ll call them and say, ‘Go run away and do something else for the day,’” he said.

“Yes,” said the executive.

“How the hell did you come up with that idea?”

“Sir, JT is keeping a knife on my neck. Ideas will come.”

Peeling sheds

Soon after he arrived, Farinella had discovered another concern: off-site peeling sheds. One was a 35-minute drive from the main production facility, the other 90 minutes away. BAP and other certifications forbid the use of off-site peeling sheds because they are tougher to regulate. The CAL report says that “peeling sheds are often hidden and rarely audited.”

The two sheds that Choice Canning used processed 2,200 to 3,300 kilograms of shrimp per day — roughly half the quantity that the company shipped to the US, according to Farinella and from dozens of daily production reports. (The company has since said that none of the shrimp processed in these sheds was for BAP customers. It did not specify where this shrimp was sold.)

Throughout his time at the plant, Farinella received a relentless stream of messages from the senior leadership. Thomas, the chief executive, often seemed incensed at hygiene shortcomings.

“Get this cold store mess solved at the earliest,” he wrote in a WhatsApp message. “Whoever did this will suffer in life!”. One day, after being shown a photo of the site in good order, he said that he had just been told that $80,000 worth of his produce had to be thrown away because US customers complained about the smell. “How do I believe your photos?” he wrote on WhatsApp to his staff on-site.

But Farinella also felt stonewalled when he tried to make improvements. “When I would tell JT what changes I needed to make I would be flat out told ‘no’.”

Farinella was also under constant pressure for not generating enough revenue. In a recorded Zoom meeting on 6 February, between Farinella and three executives, including Thomas, the leaders expressed frustration with Farinella for being insufficiently productive, using what Farinella described as the “usual veiled threat of firing.”

“I don’t know what your January results are,” Thomas said. “You should be more concerned than I am.”

***

In January, Farinella finally decided to go public with what he knew about the plant and contacted a journalist. “I think it is likely that I was hired not to manage the facility, but to be the American face that provides the appearance of legitimacy,” he said. For a plant with so many problems, he added, “I’m afraid I can’t be that face.” (To further explore how this investigation was conducted see the methodology page.)

A videographer travelled to India to document conditions at the plant. Farinella was so on edge that when he saw armed police near his apartment building he felt his heart was almost “jumping out” of his chest. (It turned out to be a coincidence.)

A few days later Farinella caught a plane back to the US and emailed his notice from the airport. After landing in Pennsylvania, he stopped by a McDonald’s on his way home from the airport. “I don’t even like McDonald’s,” Farinella said. “But that was a damn good cheeseburger that day.”

Pressure was starting to wear on Farinella’s colleagues, too. On 14 February, a human resources officer from the plant contacted Farinella on WhatsApp to say that he, too, was quitting Choice Canning. The hours were ruining his marriage, he said, and the dispute with local workers over wages had wrecked his reputation. He was being threatened on the phone. “While I was going home in my car,” he later wrote in WhatsApp to Farinella, “some of the local people attacked me with stones.”

Farinella retained a lawyer in the US and filed a formal whistle-blower complaint to the FDA and several other federal agencies. He wasn’t sure what good it might do, but he wanted to state what he had seen on the record.

The same day, Aldi South’s auditors arrived in Amalapuram. They were there to conduct the inspections that the local managers had been discussing for weeks. After the audit was finished that evening, Farinella contacted his former colleagues and asked whether they had gone ahead and relocated workers during the audit. Two of the managers confirmed that they had indeed. “Exactly sir,” one wrote in WhatsApp. “All workers are sent outside.”DM

This story was produced by The Outlaw Ocean Project with contributions from Ian Urbina, Maya Martin, Jake Conley, Joe Galvin, Susan Ryan, and Austin Brush.

First published by The Outlaw Ocean Project

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Brics countries,upholders of human rights???

Corruption has no boundaries!

What are the chances that S.A. seafood are free of antibiotics? Do we check? Are importers and chairs pro-active?

Will our equivalent of FDA conduct an audit?

A veritable cocktail of evil= slave like conditions, worker exploitation via wages and health safety for consumers!

The US per capita consumption of shrimp doubled, the price halved over the same time… you don’t need to be a rocket scientist to understand how this was achieved – by widespread exploitation of the labour force and manipulation of quality monitoring systems… shocking, shocking!