GUEST ESSAY

Crime bytes — how easily you can be lured by criminal scammers without even realising

A cautionary tale from the Big Apple — even the savviest among us, like New York magazine's own financial advice columnist, can fall prey to a scammer's smooth talk and lose a hefty chunk of change.

Last month a story appeared in the venerable New York magazine. It was written by one of their columnists, Charlotte Cowles. In a remarkable display of self-recrimination and with embarrassing honesty, she recounted how she had recently been scammed. She lives in New York and is a happily married mother. Given her career, one would assume she spends time with smart, educated, worldly people.

However, as it happened, after a series of phone calls from someone she didn’t know, she ended up withdrawing $50,000 in cash (most of her savings), putting it into a box and giving it to a stranger in a black Mercedes. All of this without any threat of physical violence.

The story of how this happened to her is really quite entertaining, in a watching-a-trainwreck sort of way. Afterwards, people could not believe that she fell for it, that she told neither her husband nor the police as it was unfolding. But she didn’t. Instead, when she worked up the nerve, she reported her experience in a major cultural outlet, knowing that it would go viral.

I won’t repeat the devilishly clever details of the scam in this despatch; you can read about it here. The point I want to make is that Ms Cowles is probably very much like you and me. We are all no more than inches from scamster victimhood, no matter how alert we may think we are. (Ms Cowles is New York magazine’s financial advice columnist, a fact which requires no further comment.)

As a sometime crypto columnist, I was quite taken by this story because there was no mention of Bitcoin; this was a cash-only deal, entirely negotiated via old-fashioned voice conversations on a cell phone.

By pure coincidence, a couple of other non-crypto scams crossed my field of vision in the same week. A Facebook friend who bought an item from an international store was asked to pay a small shipping cost first, after which R15,000 was charged to her account at a French retail store, unrelated to her original purchase. Presumably, the first payment somehow allowed the scammer to push the second one through.

Read more in Daily Maverick: No con do! — here’s how to spot the scam red flags and stay safe

I am also watching a new show on Netflix called Emily the Criminal, set within the ‘dummy buyer’ industry. A dummy buyer is basically a mule who is supplied with a home-manufactured credit card embossed with a valid name, number and correct magnetic strip details, as well as a counterfeit driver’s licence to match the name on the card. The dummy buyer goes to a store, buys a massive flat-screen TV (or whatever) with the counterfeit credit card and driver’s licence, takes it out to the parking lot, gives it to a guy higher up the chain, and is paid a few hundred dollars for her trouble. The TV show is fictional but, apparently, this method of stealing is a giant industry.

How does this work? Well, there are millions of stolen but valid card numbers for sale on the dark web for a few dollars each, and you can manufacture new cards all day on your kitchen table with $100 worth of over-the-counter equipment. The same dummy buyer never visits the same store twice and the card is never used twice. Simple and safe. Mind you, it should be mentioned that many credit cards in the US do not use PINs; the scam would be more difficult elsewhere.

Around the same time, I listened to a disturbing episode of a podcast called Search Engine. It relates the story of an obsessive amateur sleuth who wanted to find out who was behind the WhatsApp message we all get occasionally that reads something like ‘Hi, this is Charlene. Remember me?’. Most of us block the sender.

This man didn’t. He set out to get scammed, and ended up going to Cambodia to a beach town called Sihanoukville. There, in a neighbourhood called Chinatown, he found large, fenced and guarded factories in which young men and women from countries like Laos find themselves after responding to advertisements for ‘customer service’ jobs. On arrival, they are immediately incarcerated and forced to work on scams (often of the charmingly named ‘pig butchering’ kind of romantic deceits, or get-rich-quick investment schemes). Those who do not make enough money for their criminal bosses are beaten, tortured and sometimes killed. The podcast is chilling, and the problem seems intractable.

Creepily, as I typed this last paragraph, the following popped up on my WhatsApp screen:

‘Jou finansiële rekening is bygevoeg. Rekening: Amk329 Wagwoord: sk2210 USDT Saldo: $2,170,096.50 [ usdtadop.com ] Hou dit asseblief op ‘n veilige plek’.

Or, translated:

‘Your financial account has been added. Account: Amk329 Password: sk2210 USDT Balance: $2,170,096.50 [ usdtadop.com ] Please keep it in a safe place’.

I blocked the account, whose originating cell number is from Indonesia, notwithstanding that it was in Afrikaans. Notice the strange umlaut over the ‘e’ in ‘finansiële’.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Banking scam — international crime syndicate targets South Africans using smartphones

How big is the online scam industry? I went off in search of numbers.

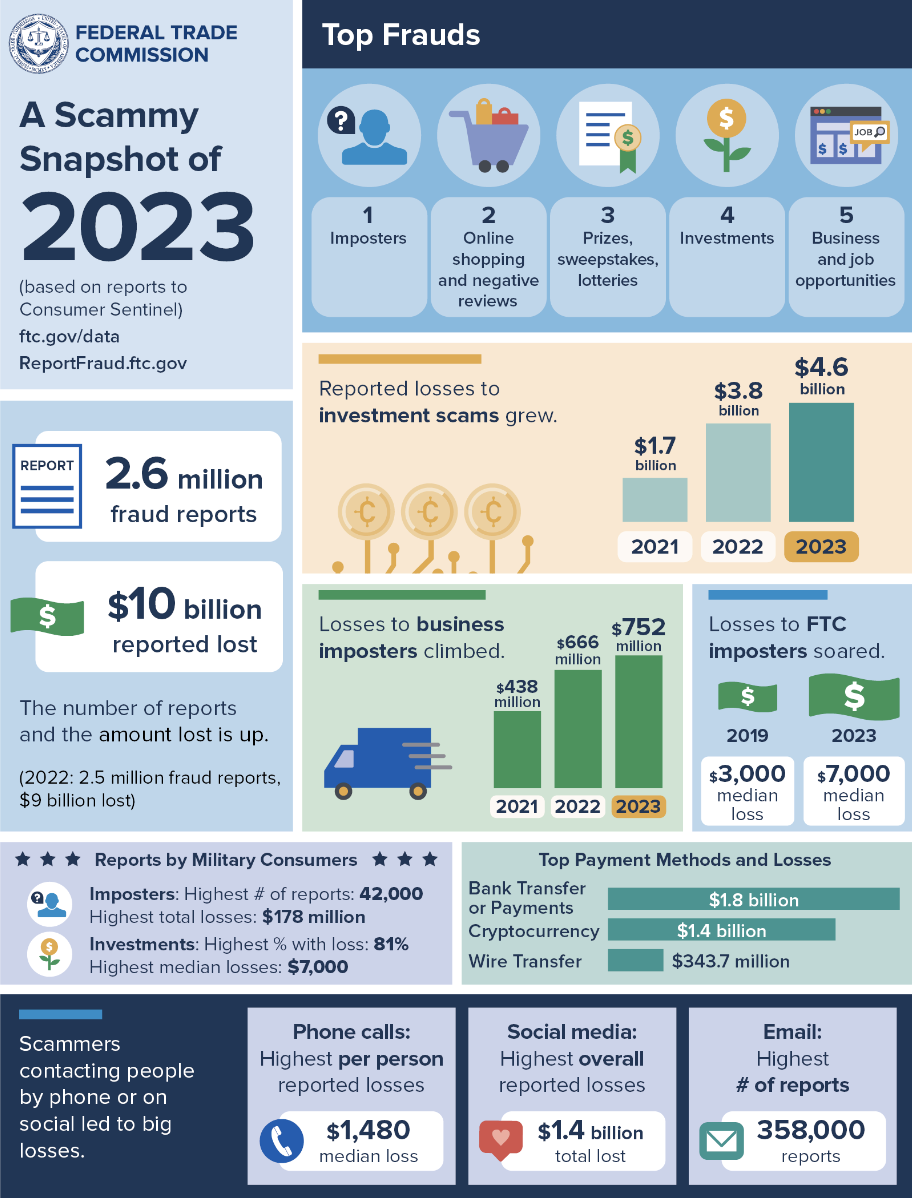

One of the most recent sets of figures comes from the US Federal Trade Commission, here. Over $10-billion in fraud was reported to the FTC in 2023, a 14% increase. The graphic below neatly illustrates the highlights.

The sheer scope of these mendacities is pretty audacious. One wonders if there are scam rooms, like the writer’s room in the TV industry, where creative criminal geniuses toss ideas around over coffee and donuts, shaping them into narratives that have the best chance of hitting their targets.

One of the problems with scam statistics is that many people do not report their experience, out of embarrassment or even fear. So we have to assume the FTC report is a subset of a much larger total, one that is harder to pin down.

In 2023, Ofcom in the UK used a survey to try and get closer to the truth. Keep in mind that this study only surveyed online scams, whereas the FTC included the entire gamut. Here are the sorry stats (quoted off the Ofcom website):

- ‘Around nine in 10 online adults in the UK (87%) have come across content they suspected to be a scam or fraud.

- Nearly half of the participants in the study (46%) said they had been personally drawn in by an online scam, while two in five (39%) knew someone else who had fallen victim.

- A quarter of those who said they’d encountered online scams had lost money as a result (25%) — with a fifth (21%) being scammed out of £1,000 or more.

- More than a third (34%) of all victims also reported that the experience had an immediate negative impact on their mental health, increasing to nearly two-thirds (63%) among those who had lost money.

It struck me that the word scamsters is too jaunty, too light-hearted. These many thousands of people are frightening criminals and they are everywhere around you, at all times, on every device and across every channel. Probing and pressing, looking for vulnerabilities, ubiquitous and determined. And this is even before AI takes hold and fine-tunes the efficacy of malfeasance.

It is distressing to contemplate. The first question that anyone looking at these statistics will ask is how do we protect ourselves? In response, the Interweb fairly groans under the weight of well-intentioned advice. I have little confidence in these entreaties, however, as I am sure the hapless Ms Cowles must have read some of it before, as have the rest of us.

The best strategy is to unplug your computer and go and read a nice book. Sorry, that’s all I’ve got for you. DM

Steven Boykey Sidley is a professor of practice at JBS, University of Johannesburg. His new book It’s Mine: How the Crypto Industry is Redefining Ownership is published by Maverick451 in SA and Legend Times Group in UK/EU, available now.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

finansiële – that is actually the correct spelling. It is not strange at all, and the diacritic ë means the word should be pronounced fienansiehele instead of fienansiele (in sort of phonetic Afrikaans spelling)

FYI, it isn’t a strange umlaut. It is grammatically correct in Afrikaans.