BOOK EXCERPT

‘How to Fight a War’ by Mike Martin — having an unrealistic strategy is the most common mistake leaders make

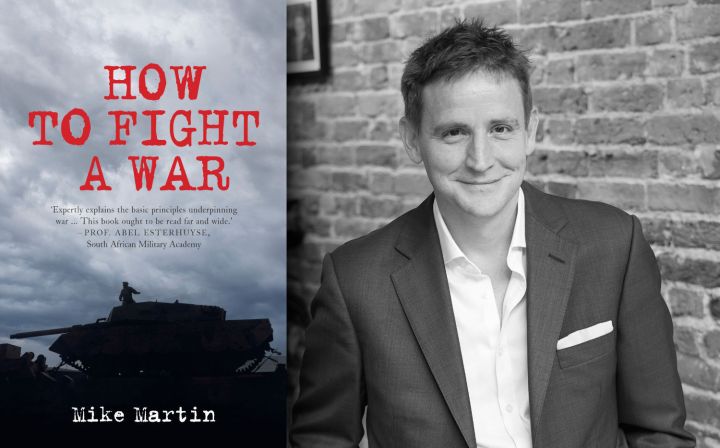

‘How to Fight a War’ is an indispensable guide to understanding modern warfare, especially the decisions made by politicians and generals – good and bad. Read an excerpt from Mike Martin’s latest book.

Has any war in history gone according to plan? Monarchs, dictators and elected leaders alike have a dismal record on military decision-making, from overambitious goals to disregarding intelligence, terrain or enemy capabilities.

This not only leads to deaths but also usually sows the seeds for more wars down the line.

In How to Fight a War, conflict scholar and former soldier Mike Martin takes the reader through the hard, elegant logic to fighting a conclusive interstate war that solves geopolitical problems and reduces future conflict. Read the excerpt below.

***

Chapter 1: Strategy and intelligence

The single most important thing that the leader of any military force must do is to develop a realistic strategy. That this is salient in the practice of warfare has been known for millennia. Indeed, Sun Tzu wrote 2,500 years ago that ‘strategy without tactics is the slowest route to victory; [but] tactics without strategy is the noise before the defeat’.

Having an unrealistic or otherwise flawed strategy is the most common mistake that leaders make when committing their forces to war. Your country, empire or coalition may have the biggest, best-equipped and most highly trained army in the world, but without a realistic strategy set by the leader, your war will always fail in its aims. So, although what follows is one of the shorter chapters in How to Fight a War, if you only read one chapter, read this one.

Originally from the Greek word strategia meaning generalship, ‘strategy’ is one of the most misused words in the English language. Often it is confused with ‘plan’, as in a sequence of actions, whereas a ‘strategy’ is far more all-encompassing. It comprises an understanding of the world, a set of overarching, How to Fight a War high-level objectives or goals, a description of the methods to achieve those goals (a plan), and which resources are needed and should be used. Generalship is much more than just a plan.

You can tell when a country or a leader lacks a realistic strategy because they tend to list either activities (‘we are launching airstrikes’) or ill-defined goals (‘X country must lose’) in the place of an unambiguous, realistic goal (‘we are going to remove the armed forces of X country from the territory of Y country’). In other words, they are confusing activity for output.

Another obvious ‘tell’ is when a country’s war aims keep shifting from one thing to another: this reveals that they have not thought through their overarching objectives and are being blown from one to the other as events unfold. A leader and a country must carefully select, and then continue to follow, their overall strategic objectives: this is a fundamental principle of waging war.

A good strategy should contain clear, simple objectives. In the Second World War, the Allied Powers’ (the US, Britain, the Soviet Union, and others) goal was the total defeat and unconditional surrender of the Axis Powers (Germany, Italy, Japan, and others). These defeats were to be sequenced: the Allies decided to ensure the defeat of Germany and Italy before the defeat of Japan. While Germany and Italy were being defeated, the Allies fought a lower prioritised war against Japan. This was because in the realistic intelligence assessment of the Allies, Nazi Germany represented a much stronger and more dangerous foe who, were they able to defeat the Russians and the British in Europe, might become unassailable.

This was known as the ‘Europe First’ plan. In a testament to the enduring nature of the Allies’ strategy, it survived even the Japanese attack on the United States at Pearl Harbor, where quite reasonably the United States might have reconsidered that Japan was the more immediate threat. The resources required for this strategy precipitated a series of other objectives, not least among them winning the Battle of the Atlantic, so that Allied supplies could cross from the United States to Britain and Russia. And it was because of the immense resources required that the Allies decided in the first place to sequence the defeat of their enemies, rather than to take them on simultaneously.

You will see from this example that the components of strategy can be shortened to Ends (overarching objectives: the defeat of the Axis powers), Ways (the sequence of actions, or plan: the Europe First plan) and Means (the resources required to carry out your plan: American supplies used by Britain and Russia). Your strategy – with its Ends, Ways, and Means – must rest on a solid, objective understanding of the problem you are trying to solve with military force, and of the wider world in general (the Allied appreciation of the relative strengths of Germany and Japan).

A good strategy should also offer you a framework against which to judge potential actions. That is, if you do X or Y, which of the two is more likely to achieve your eventual aim(s)? This is particularly important in war, because for most of the time the ongoing fighting is at best confusing. It will be hard to discern who is winning a particular battle, or (especially) what the enemy leader is thinking. A realistic strategy will help you cut through that ambiguity and focus your limited resources on achieving your overriding objectives.

In early 1941 the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill was faced with the critical decision of whether to keep several hundred newly-produced tanks in Britain to help defend it from invasion, or to send them to the Middle East where they would help defend Egypt (at that time under British control) from the German and Italian armies.

In the end the decision was made to deploy the tanks to the Middle East where they would help secure British oil production and the strategic prize of the Suez Canal which at that time supplied Allied forces in the Mediterranean, the Middle East, and the Far East. It was judged that were the Canal and the oil to fall into enemy hands, Britain would likely lose the war. There was no option but to send the tanks to Egypt, even while incurring the risk of Britain being less prepared to defend itself in the event of invasion.

The best way to visualise strategy is as a three-legged stool with Ways, Ends and Means each comprising one leg, and with the stool resting on the foundations of a sound understanding of the problem/enemy you face, and the worldwide context.

In theory, it is simple to decide upon a strategy. But in practice, it is rarely achieved. This is because the simplicity of the concepts outlined above are often obscured by humans’ inability to understand the world objectively, or think through strategy clearly, without falling foul of their own cognitive biases. When leaders or countries produce poor strategies, it is because they have been unable to escape their own biases. These biases exist because of the way that human cognition evolved, and are completely unavoidable. If you think that you do not have cognitive biases, you should be aware that one of the main cognitive biases is thinking that you do not have any biases.

How cognitive biases affect intelligence understanding and strategy formation

Understanding the world using intelligence and forming strategy are both prone to several well-established human cognitive biases. The most common of these is overconfidence (or hubris), something that leaders are often prone to, and which you must guard against. The ease with which British and American leaders felt that they would reconstitute Iraq after the 2003 invasion is one obvious recent example, which meant that they did little or no planning for the aftermath of the war, and the country quickly descended into chaos.

This overconfidence is exacerbated by obsequiousness bias, namely our tendency to agree with the statements of those above us in the hierarchy. If you the leader projects confidence (as leaders do), your troops will often nod along, not wishing to go against the hierarchy. The Coalition and then NATO operations in Afghanistan, from 2001 to 2021, offer a salutary tale: every year the officers in the field reported steady progress, and that the coming year would be the decisive one, where a corner would finally be turned. In reality – and as evidenced by the collapse of the Afghan government and security forces before NATO had even left – there was little or no progress being made. As leader, these two biases are the hardest for you to counteract – resting, as they do, upon your own personal psyche and power base. You must continually guard against them.

The other type of bias that you must beware of – and this is linked to overconfidence – is becoming sucked into a status dispute with your opposing leader. That is, of personalising the war and making it about You versus the Enemy Leader. All leaders are driven by achieving status and have become leaders by seeing off multiple status challenges in their own political parties, militaries or countries. Once they become leader of their group, this habit of seeking, guarding against, and winning status challenges transfers to the leaders of other groups. And when this happens, wars can become about beating the other leader, or humiliating them, rather than achieving strategic outcomes for your country. DM

How to Fight a War by Mike Martin is published by Delta Books (R290). Visit The Reading List for South African book news, daily – including excerpts!

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Hearts and minds

Care has to be taken to not alienate the local population. Alienate the local population gives you a guerrilla war and a war that is un-winnable. Furthermore popular support back home diminishes when civilian casualties reach unacceptable levels.