MEDIA OP-ED

News industry meltdown — market failure or creative destruction?

The recent tsunami of bad news about the news industry has raised an interesting question. Are we seeing the effects of a market failure play out, or are we seeing the death of an industry that failed to innovate and keep up with the times?

The term “creative destruction” was coined by the economist Joseph Schumpeter in 1942 to describe the dismantling of established processes to make way for new ones. A bitter and uncomfortable shedding of deadweight as new products or technologies lead to the demise of the old ones.

Think of camera film and Kodak, the often-studied business school case study of product disruption. Few tears were shed as the world embraced digital cameras and smartphones because digital photography was easier, cheaper and better.

The New York University journalism professor Jay Rosen summarised many things that contributed to where we find ourselves — we scored many own goals. Is journalism past its sell-by date, as some have argued? And does it matter whether it’s a market failure instead?

Here are some thoughts.

First, it is important to distinguish which is playing out. Mostly because, if we are indeed seeing market failure, the best and usually only response is for regulatory intervention and government support.

If it’s a plain vanilla disruption of the Kodak kind, we will see new products and services fill the void of journalism, and society will be better off. Societies and democracies shouldn’t decay, migrating from the news equivalent of camera film to digital.

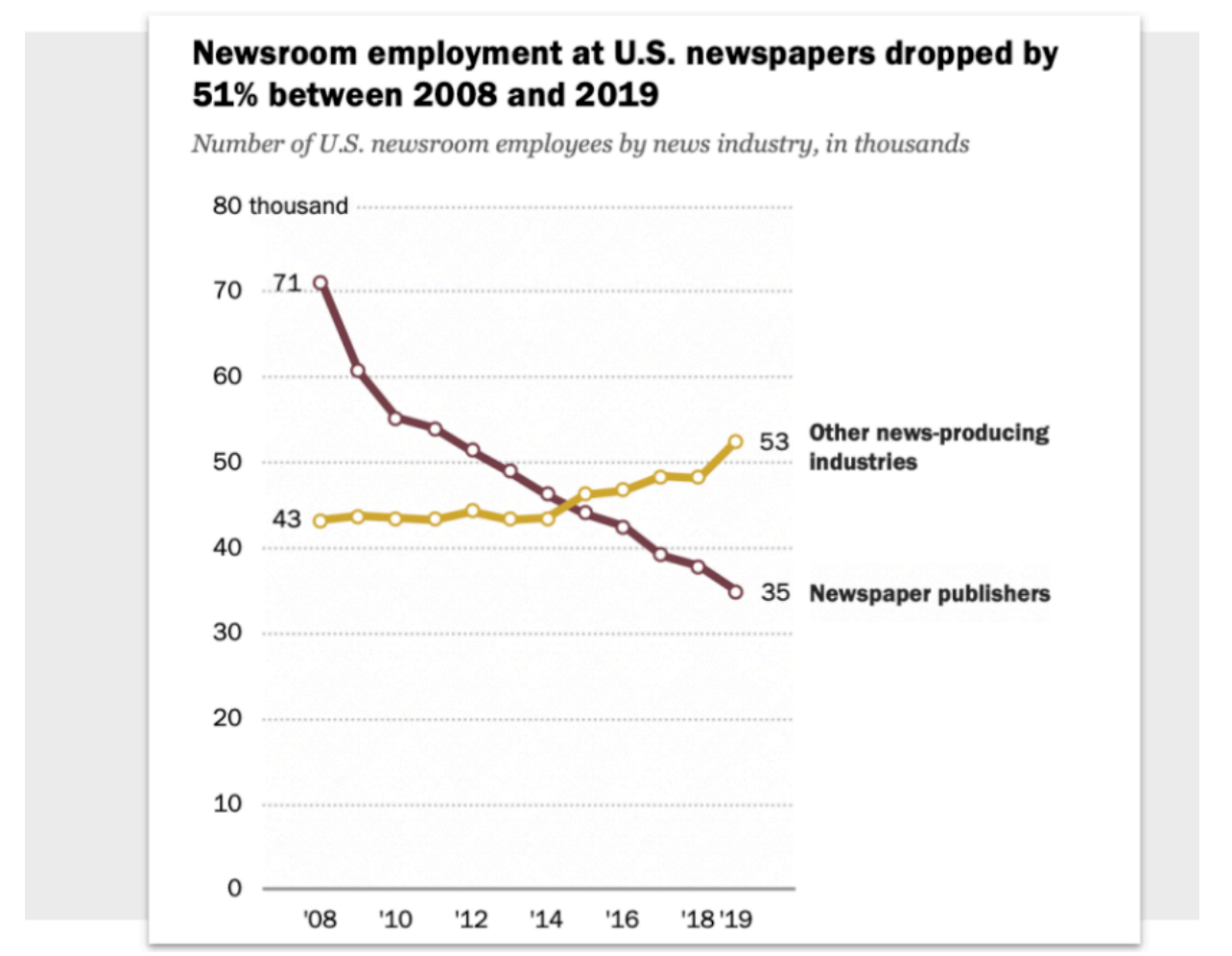

It’s also important to separate the newspaper segment of the industry from broadcast news on television and radio. Studies have shown that newspaper newsrooms provide more original news reporting than any other over time and are probably responsible for most groundbreaking investigations that change our world. Yet, they are the ones that have suffered the most financially.

Market failure argument

The argument for market failure hinges on the idea that public service journalism, especially local and investigative reporting, is a public good underprovided in a broken market system.

Anyone following the turmoil of the last 20 years will know that the digital revolution has severely disrupted the economics of the news industry. Advertising revenue, once the lifeblood of the industry, has massively shifted to tech giants like Google and Facebook, leaving news outlets gasping for sustainable revenue models.

This could be seen as a failure of the market to support vital democratic functions of the press, such as holding power to account and informing the public.

Additionally, the proliferation of free content online has led to a devaluation of quality journalism in the eyes of many consumers, who might not differentiate between well-researched, fact-checked reporting and more sensationalist or biased content. Or a TikTok created in a teenager’s bedroom.

This could be seen as a market failure where consumers do not adequately value a crucial product for democracy, but it is still valuable and sorely needed.

Adding an extra layer of complexity is when a few players (à la The New York Times, Financial Times, etc) are winning. “Winner takes most” is a common theme in news industry reports, epitomising the problem where a global publisher like The New York Times is seen as a competitor for local news subscription budgets.

Journalism as a public good

The other element of the market failure argument is whether journalism is a “public good”. Usually, public goods are provided by governments, are not for exclusive use and can be used multiple times.

The South African National Editors’ Forum settled on a definition that public interest journalism refers to journalistic activity that is central to the democratic function and the protection and promotion of the Constitution, including investigative journalism, reporting on the daily affairs of public institutions and local journalism focused on the generation of public interest stories in towns and villages and underserviced rural areas.

So, while not all journalism is a public good, much journalism is created in the public interest and can be argued as such. While not as clear-cut as roads, clean water and air, the democratic value to society of public interest journalism is, in my book and that of many others, a public good.

Creative disruption argument

On the flip side, the argument for creative disruption posits that the challenges faced by the news industry are a natural part of technological advancement and evolution within the media landscape. The US journalism professor Jeff Jarvis asks whether it’s time to give up on old news because “legacy” journalism has failed to become a service to society and be driven by the needs of those audiences it claims to serve.

From this perspective, the internet and digital platforms have democratised content creation and distribution, breaking down the barriers that once kept news media as gatekeepers of information. This has led to an explosion of new voices and perspectives, arguably enriching the public discourse.

Shifting business models towards digital reader revenue, subscription, membership and crowdfunding are emerging as news organisations adapt to this new environment, albeit with few success stories.

This can be seen as a healthy, albeit painful, transformation that pushes the industry towards more direct and engaging relationships with its audience, fostering loyalty and community.

The follow-up question is: at what cost to society? When Kodak and other camera film manufacturers developed their last negatives, society was unchanged, and many would argue that it was better off. Can we say the same if the news industry continues to haemorrhage in the way it has?

Poor leadership, failure to innovate and clinging to old practices have certainly been factors in the demise of many news outlets. Not to mention those who operate in the extremes of the attention economy, seeking to monetise our anger and fears.

But many news practitioners are doing incredible work in heartbreaking conditions and getting nowhere, thanks to economics that no longer work.

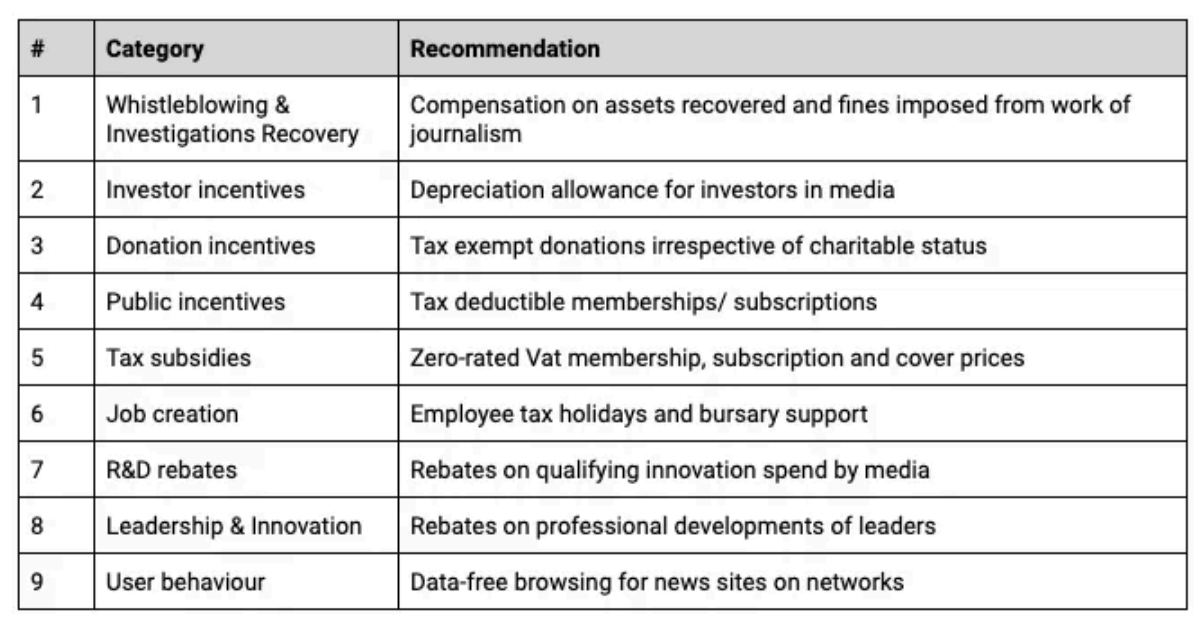

If we agree that the system is broken AND that there is still immense value to society for that product/service, regulatory intervention is the only response that can restore a semblance of normalcy.

These take the form of incentives and subsidies to encourage behaviour changes from members of the public, advertisers and publishers themselves. I write about these possible measures in detail here, taking guidance from successful European efforts, sustainability research reports and other government-supported industries. They include:

Some regulatory measures and incentives to sustain media

For some, government intervention might sound scary, but there are many examples where it can and has been done in a supportive and helpful way.

There are many precedents we can lean on and measures that can prevent systemic abuse. In 2009, the Federal Trade Commission in the US held discussions with industry players around policy recommendations to support the “reinvention of journalism” in the internet age. “Market failure” was already bandied about then, and some of the recommendations look quite appealing when viewed through the lens of an extinction-level event.

In countries where subsidies exist, like those in Scandinavia, we also find high press freedom scores and stellar corruption perception scores. More importantly, we see some of the healthiest news media organisations in the world. Regulatory support is not the only factor, but it is surely significant during periods of mass disruption to provide the space for innovation.

Those practising public service journalism feel very much like Sisyphus — destined to push boulders up neverending mountains. We don’t need any more proof that the system is broken; we need supportive measures for a critical industry. Now. DM

Charalambous is the co-founder & CEO of Daily Maverick.

First Published by Medium

So social media is the “digital camera version,” the future version, of newspapers?

I hope not. The trajectory would be abysmal. Being in my middle 30s and having spent the first few years (early 1990s) on a farm in Mpumalanga, I started life with a “nommer asseblief” 4-digit phone number and viewing slides on a projector in the darkened lounge. Each phone calls mattered and each photo was an attempt to capture a precious moment. Compare that with all day texting and robocalls and a trillion selfies.

I’m not saying I would go back by any means, but there seems to have been a happy medium we blew right past.