BUSINESS REFLECTION

After the Bell: Macro projections are very wrong but weirdly, still important

Investors and asset-management companies are taking increasingly less interest in macro figures, but these projections are important for economic planning purposes because markets around the world, particularly commodity markets, do follow them.

The IMF did something unusual on Tuesday, releasing its global economic forecast from South Africa instead of from Washington. The organisation clearly recognises it has work to do on getting the SA economy right, because its estimates have generally been ludicrously overconfident, as have the government’s, for more than a decade. For example, at the start of last year, its estimated GDP growth for SA at 2.1%; on Tuesday, it updated its estimate for calendar year 2023 to 0.6%.

It was twice as wrong about SA than it was about any other major economy or region and the reason was, of course, the surprising implosion of Eskom and Transnet, which caught the IMF off guard. Clearly, they don’t read this column.

But it does raise the question, what is the actual value of macro forecasting? At this time last year, according to one survey, 85% of economists in the US were anticipating a recession. This is the most watched, most analysed, and most data-transparent economy in the world: how could so many economists get it so wrong?

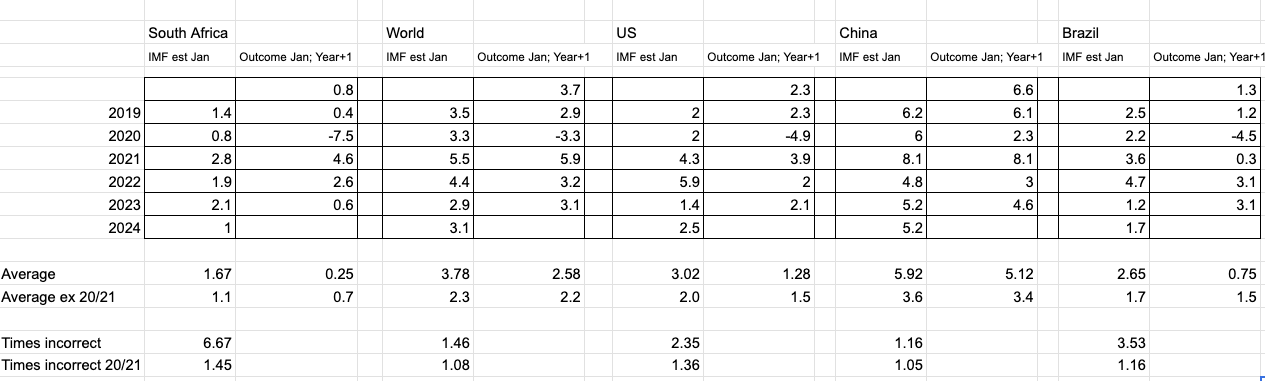

To answer this question — which I’ve grappled with in the past, but bear with me — I did a quick exercise. I took the January edition of the IMF’s premier publication, the World Economic Outlook, for the past six years, and I compared what the organisation anticipated at the beginning of each of those years (the publication is updated every quarter) with the actual outcome. The IMF does not do this exercise — nobody likes to admit their mistakes too publicly — although it does record the differences in its projections quarter by quarter.

For SA, as I said, the projections are ludicrously rosy. Of course, you have to bear in mind the effect of the Covid years, which understandably made a mockery of growth estimates for 2020 in particular. Average growth estimates for SA were 1.67% and the outcome was 0.25%.

That is very wrong, but how wrong is it comparatively? The answer is that it is pretty badly wrong, much worse than the substandard results you get from making the same comparison with the world and even with another medium-income country, Brazil.

But let’s cut the IMF some slack here and exclude the Covid years of 2020 and 2021, which were crazy difficult to estimate, and what we get is much more accurate. If you do that, then for example, the IMF was just a wee bit too confident, suggesting a 2.3% global growth compared to an outcome of 2.2%.

For individual countries, the picture is more mixed, as you would expect, because the averaging effect across the globe tends to minimise individual mistakes. A good example is this past year when the IMF was estimating US growth at 1.4% and it seems likely to come in much higher, at 2.1% — and with no recession to speak of. Surprisingly, or perhaps not, the IMF’s projections on China have come in very accurate, even including the Covid years.

Just to make one general point: the differences between the estimates and the results seem very small, a matter of 50 basis points in many cases, but don’t let that fool you; the absolute quantities are enormous and very small differences in estimate-to-outcome can mean huge differences in the quality of life for ordinary people.

For example, a 50 basis point miss in global GDP translates to a country the size of SA disappearing off the global economic map. Or to put it another way, every one percentage point miss means the world produced about a trillion dollars in goods and services less (or more) than anticipated. This is chunky change.

Economic planning

To come back to my point about the importance of these projections, they are important for economic planning purposes because markets around the world, particularly commodity markets, do follow them. For example, the IMF was pretty gloomy this time last year and global commodities dropped in value on average by about 12% over the calendar year. The projection of the same sort of growth this year as last year, is therefore not great news for commodity businesses, or commodity countries for that matter.

But imagine you are a businessperson and the IMF, and everybody else, says there is going to be a recession in the world’s largest economy and instead it grows at a healthy clip. What kind of opportunity cost has gone missing there? I suppose, for that reason, the IMF and other institutions are generally over-confident: you don’t want to create a self-fulfilling prophecy.

But increasingly, investors and asset-management companies are taking less interest in macro figures: they are too generic to make a real difference, and, without putting too fine a point on it, too wrong. It’s much easier to look at individual businesses, their cash flows and their prospects. Yes, these operate in a context, but the macroeconomy applies equally to everyone, after all, so where is the differentiator?

Still, one sympathises with the IMF and everyone else doing macro projections. To repeat the old joke, predictions are really difficult, especially when it comes to the future. DM

Comments - Please login in order to comment.