BUSINESS REFLECTION

After the Bell: How worried should we be about the world’s ten biggest companies?

What are these ten companies? This is pretty obvious: six of the ten – and the top six at that – are tech companies.

I guess like most people, I’m an enormous fan of telling other people what to think and do, side-stepping most suggestions in this respect that might apply in the reverse. In a way, it’s inevitable. It would be difficult, if not impossible, to act if we didn’t believe our actions were correct. Action is predicated on belief; that’s how we roll.

But after many years of failure, I have come to learn the hard way, there is an exception to this rule: The stock market. When investing, it’s important to try to lose your natural inclination to tell the market what it should be doing, and rather listen to what it might be telling you.

The reason is simple: the stock market is designed to make you look like an idiot. It just will. It is partly for this reason that I have taken care over the years not to accumulate any wealth of any consequence. If I had, what would have happened is that I would have developed a convincing theory, and I would have lost thumping great chunks of that wealth going “all in” on it. And by “convincing theory” I mean a theory that I used to convince myself, not a theory that is in any way actually convincing.

I suspect this is the reason why people have financial advisers. It’s not necessarily that they trust their financial advisers to make them more money, although most do. It’s the desire to have someone to blame if things go wrong. It’s so much more satisfying than blaming yourself.

The reason for this rather elongated introduction is that there is one respect in which global stock markets are currently hugely out of kilter, and I can’t help wondering what the markets are trying to tell us – if anything.

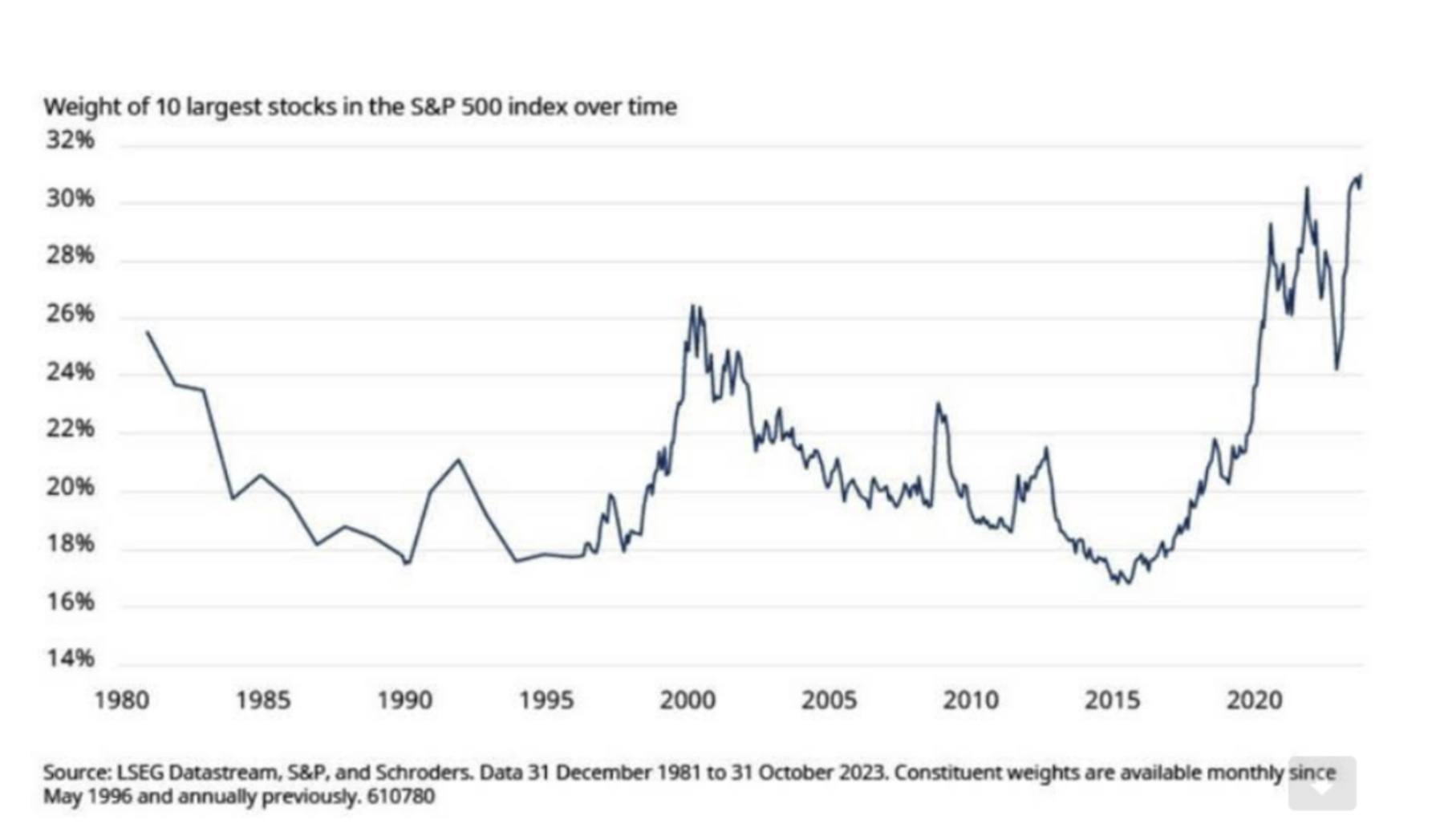

In a note to clients, Duncan Lamont, the Head of Strategic Research at investment bank Schroders, draws attention to an interesting statistic: global stock markets have become very top-heavy. Just to take one measure, the ten biggest stocks in the S&P 500 index currently make up a record 31% of that market. The average over the past 50 years is about 22%.

That is remarkable enough in itself, but it’s worth noting that a mere eight years ago, that proportion was sitting at around 17%. What grand change have we seen over the past eight years?

It’s not just something that has happened on the US stock market, Lamont points out. The US market itself has become very dominant in the global stock markets, growing to be 63% of the global market at the end of October (MSCI All Country World Index (ACWI) index) so international investors have ended up with a lot in US stocks and, with that, a lot in only ten stocks. Those ten make up nearly 18% of the global market, the same as Japan, the UK, China, France and Canada combined.

Lamont draws from this calculation that investors should beware because passive investors often lose after periods of concentration because concentration does unwind. For Lamont, it’s a demonstration of the utility of actively managed portfolios. Historically, deviating from the market has been a winning strategy when concentration has been high, he writes.

Uncharted territory

But is this true? Lamont himself acknowledges we are in uncharted territory to an extent. Apart from the ongoing active/passive debate and to come back to the original question, what is the market trying to tell us here?

Well, what are these ten companies? This is pretty obvious: six of the ten – and the top six at that – are tech companies: Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Nvidia, Alphabet (Google) Meta (Facebook). There are also two pharmaceutical companies in the group, United Healthcare and Eli Lilly, as well as investment house Berkshire Hathaway and car maker/tech company Tesla.

But although the group is dominated by tech companies, it’s interesting to me that their businesses are all very different. Apple, you could say, is actually a marketing retailer; Amazon is also a retailer, but not generally a seller of its own products; Google and Microsoft are software companies; Meta is a social networking company; and Nvidia is a chipmaker. Calling them “tech” companies is only true in a very generic sense.

I think four things bring them together: they are truly global companies; they are American; they are (relatively) young; and they are dominant in their respective sectors. Their American-ness allows them to tap a huge investment market. Their youth means they have developed new systems and management styles and allowed them to tap new markets. And their global nature suggests that they have been able to exploit global markets in a way that really surpasses what we have known before. There have been big, international companies before, of course. But not like this.

Their dominance is also an important factor; to be unseated, new competitors will have to emerge, and frankly, I just don’t see them, unless the big Chinese tech companies can find a way to develop their international appeal.

When you look at history, their dominance seems overdone. But when you look at the companies themselves, their dominance looks a lot more secure. DM

Comments - Please login in order to comment.