THE CONVERSATION

What does an orchestra conductor really do?

What does a conductor do when they stand up and move their hands and baton? What is their role? And how has their way of leading evolved?

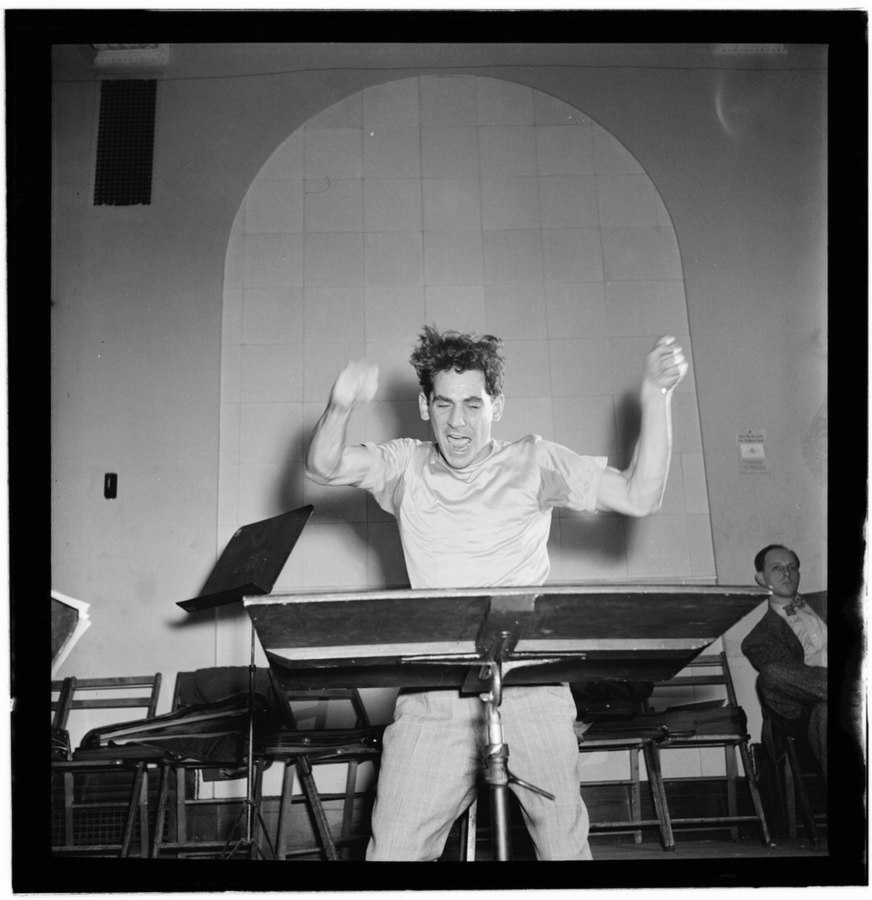

In recent years there have been many films about orchestra conductors. At the beginning of this year we had Tar, based on the conductor Marin Alsop. Also premiering soon are Divertimento, a film about the creation of an orchestra of the same name by conductor Zahia Ziouani, and Maestro, a biopic of the charismatic Leonard Bernstein.

In films such as these, you can sense the halo of mystery that surrounds the figure of the conductor, which composer and music critic Robert Schumann called “a necessary evil” as early as 1836.

Portrait of Leonard Bernstein, Carnegie Hall, New York, between 1946 and 1948. Image: Library of Congress/Wikimedia Commons

To the untrained eye, the conductor stands on a podium and wildly gesticulates in front of a group of musicians who already have an intimate knowledge of the scores they are performing. The conductor is the only member of an orchestra who has no instrument, and makes no sound of their own throughout the performance. This begs the question: what contribution does a conductor make to the quality of an orchestra’s sound?

We will focus here on their two basic functions: technical and expressive leadership.

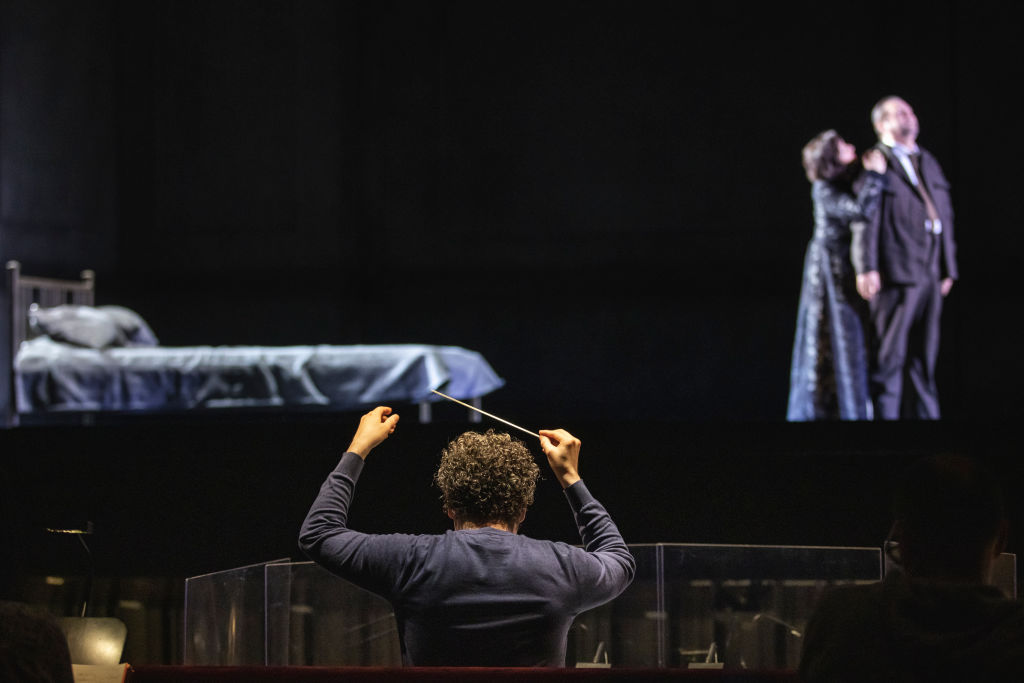

Musician and conductor Gustavo Dudamel directs the rehearsal for Verdi’s opera ‘Otello’ at the Gran Teatre del Liceu on March 24, 2021 in Barcelona, Spain. (Photo by Xavi Torrent/Getty Images)

Musician and conductor Gustavo Dudamel directs the rehearsal for Verdi’s opera ‘Otello’ at the Gran Teatre del Liceu on March 24, 2021 in Barcelona, Spain. (Photo by Xavi Torrent/Getty Images)

Keeping time

If we closely watch the conductor’s movements during a concert, we will soon notice one of these roles, which is keeping the piece in time.

The earliest references to the need for musical timekeeping in Western culture can be found in treatises on music from the 16th century when musicians were recommended to guide themselves by tapping their hands or feet. However, the first symphonic orchestral ensembles during the 18th century – the era of musical classicism that we associate with composers such as Haydn or Mozart – still had three characteristics that made the existence of a conductor unnecessary.

Firstly, the number of musicians in ensembles was small, which made them easier to coordinate. Secondly, rhythm generally stayed the same across most compositions, making it easier to maintain without an external guide. Lastly, musicians played almost continuously from the beginning to the end of a piece. It was often the composers themselves, playing a harpsichord or violin, who guided the simple beginning and end of a piece.

The first third of the 19th century, when Beethoven (1770-1827) was making his mark on Western culture, was when the need for orchestral conductors emerged. His work represented a quantum leap in terms of the complexity of compositions. The size of orchestras increased substantially, and instruments began to vary their roles in more sophisticated orchestrations.

These developments meant that formal rehearsals had to be organised before performances, often led by composers themselves. Considering that a symphony orchestra has a minimum of eighty members, it is easy to understand the need for a leader to synchronise the musicians’ entrances, as well as the rhythm and tempo of a piece. While the musicians have only their respective parts written in front of them, the conductor looks at the complete score and is, therefore, the only person with an overall vision of the piece being played.

Unique style

The ability to perform a composer’s work without their presence, which came about as a result of an international market of music publishers, leads us to the second basic function of a conductor: expressive and artistic leadership.

The gradually developing field of musical notation allowed composers to communicate specific instructions about the character and performance of their pieces. However, the notation does not even come close to comprehensively conveying a piece’s intended impact. This means that the same piece can have an infinite range of interpretations, and this is where orchestral conducting becomes extremely important.

The score annotations of composer and conductor Gustav Mahler offer a good example of this openness. He noted in a passage of his Second Symphony that “trombones, violins and violas should play only if necessary to prevent the chorus from deflating”, leaving the final decision up to the conductor. Other indications of his, such as “with maximum power” or “imperceptible, a little more agitated” give an idea of the multiple potential readings of a piece’s character.

With such a margin of interpretative freedom, the conductor is free to create their mental model of how a piece should be performed, resulting in personal versions that can be very different. These differences can be seen if we compare the opening bars of Karajan’s, Fürtwangler’s or Savall’s respective versions of Beethoven’s Coriolan Overture.

The group leader

The next step for the conductor is to persuade a group of tens, perhaps even hundreds, of musicians to coordinate their performances with the same expressive intent.

This task requires considerable leadership, as it involves making an ensemble follow the conductor’s interpretation and instruction. It not only encompasses tempo, but also the relative volume of each soloist or instrumental group, the phrasing, and conveying the nuances that will colour the piece’s overall effect.

Kerem Hasan conducts the London Symphony Orchestra at the Donatella Flick LSO Conducting Competition at the Barbican Centre on November 17, 2016 in London, England. (Photo by Tristan Fewings/Getty Images for the London Symphony Orchestra)

As in so many other fields of activity, such leadership has historically been exercised through hierarchical power structures and authoritarian attitudes. There are therefore many anecdotes of such conductors: the hot-tempered Toscanini who frequently insulted the orchestra; the capricious von Karajan who conducted with his eyes closed and hardly spoke to the musicians; and Claudio Abbado, who was gentle and polite in his manner but was known for whispering the names of musicians he wanted out of his concerts to his artistic director at the end of rehearsals.

Nowadays, musicians have more of a voice in institutions. There is also greater diversity in orchestras, a fact which demands a closer, more open and more persuasive form of leadership.

Venezuelan conductor Gustavo Dudamel, who will soon conduct the New York Philharmonic, Kirill Petrenko, who helms the Berlin Philharmonic, and the very young Klaus Makkela, recently appointed chief conductor of the Dutch Royal Concertgebouw, are great examples of conductors who add value and make an impact. They can create an environment in which the orchestra’s musicians feel stimulated, can grow artistically, and are motivated to perform music at the highest possible standards. DM

This article was originally published in Spanish. This story was first published on The Conversation. Cristina Simón is a Master in Musicology at the Universidad de La Rioja and Professor of Comportamiento Organizacional at IE University.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

I watched the YouTube video, hoping it would help me better understand what the conductor does. I’m still not clear as the musicians (violinists) are playing without looking at the conductor and vice versa.

they will look up from time to time – quick glances while they play. and with far more concentration towards the end of a break where they’ve not been playing.

some conductors will look up very meaningfully when they are communicating with a specific musician or group if instruments. others will use the baton and free hand more.

also, they will have rehearsed many times and will have a good idea what the conductor is wanting.

The lead violin, second violin, violas and cellos are pretty close to the conductor, and don’t really need to look up from their music sheets because they can see the movements of conductor’s hands quite clearly. The rest of the violins, second violins, etc can choose either to glance at the lead players or at the conductor, which you will see they do do. As for the instruments further back, they either look at the conductor or follow the timing of the players in front or next to them. There are many such cues, and keep in mind that during rehearsals the players have learned more or less what to expect from the conductor in terms of tempo, volume and other nuances.

I enjoyed this piece of the worth on conductors immensely.

Daily Maverick, please, please! Spare us all the the suffering of having to listen those boring and repetitive ads before we listen to any of these articles. They only serve to deter your readers from reading any article by those two laughing jokers! We really don’t want to hear the same repetitive as twenty times a day!

Please, please! Spare us all the the suffering of having to listen those boring and repetitive ads before we listen to any of these articles. They only serve to deter your readers from reading any article by those two laughing jokers! We really don’t want to hear the same repetitive as twenty times a day!

Humanity expresses its best self in a symphony orchestra – a large group of people collaborating to produce something beautiful greater than the sum of its parts, collaboratively taking turns to share the spotlight in service of that greater whole with a leader who makes no sound.

Great article! Thank you.