BOOK EXCERPT

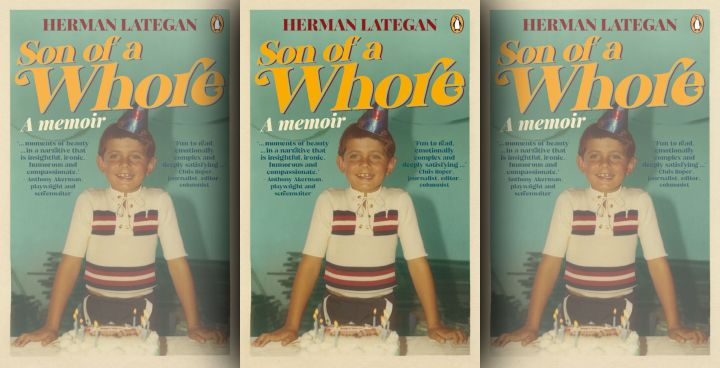

‘Son of a Whore’ — Herman Lategan’s bestselling memoir

After the runaway success of his Afrikaans memoir, ‘Hoerkind’, contrarian journalist and writer Herman Lategan has translated and updated his memoir for publication in English as ‘Son of a Whore’.

From an early age, Lategan was passed from one pair of unstable adult hands to the next. He spent some time in an orphanage, and was caught in the web of a paedophile, a well-known Afrikaans newspaperman, at 13. Shortly after his 18th birthday, when his abuser had finished with him, Herman was dumped at the door of his alcoholic father. Conscription into the army and a dishonourable discharge followed.

During his teenage years, Herman befriended poets like Sheila Cussons, Tatamkhulu Afrika and Casper Schmidt, and later, in New York, he followed Andy Warhol in the street and partied with a “smorgasbord of social butterflies”.

Back in South Africa, Herman established himself as a journalist, but struggled with alcohol and drug addiction, and was homeless for a while.

He is now an award-winning journalist, short story writer and poet.

Son of a Whore is a gripping account of loss, hardship and overcoming both. Read an excerpt.

***

It was a warm morning, one that I’ll never forget. My mother looked beautiful. I felt safe and loved. We went back to the boarding house and sat down in our room. ‘Herman, you are going to school next year. I am desperately poor. You saw that I didn’t buy anything at The Market. It’s bad. Your dad doesn’t contribute anything, no money. Nothing. I had to plan. We’ll see how it works out. We can’t just live on coffee and bread.

‘I can’t afford the meals at the boarding house. They charge extra for those; not much, but if you earn as little as I do, it’s a battle. I’m sending you to a place in Durbanville, near a school.

‘I don’t have to pay, it’s like a boarding school, but it’s an orphanage. These are desperate times. While you are there, I will try my best to get a better job, one that pays more.’

I wasn’t sure what it all meant. I’d never heard of Durbanville. So, I just sat there with my missing tooth, bushy black hair and red cheeks. That November, I turned six.

In January, my mother packed my small suitcase for me. My tiny pyjamas with the duck pattern, all my clothes, beautifully packed, firmly, in my suitcase. She closed it decisively. For a moment, we sat in silence. Ma Basson, always dependable, came. In her boat.

We drove and drove. I saw places flash by that I’d never seen before. At the back, staring through the window, I began wondering about my new life. A new life that would leave permanent psychological scars, but I was unaware of that as I sat and waited for the short and wonderful life I’d had to end.

We drove through big gates and the car stopped. We got out. A woman came to the car, shook my hand and introduced herself as Tannie Prins. Then my mother kissed me. Ma Basson was close to tears. I went and sat on a bench under a tree with Tannie Prins. She held my hand. This scene would repeat itself in my memory over many years. To this day, in fact. I watched as my mother and Ma Basson drove away. My mother turned around, looked at me and waved. They left through the big gates.

A black hole sucked me in. I was outside my body, adrift in space. The vision of the open gates paralysed me. Tannie Prins squeezed my hand again. I wanted to talk, but I had no words. They flew away, through the gates, with my mother, Maria.

The rest is vague. I can remember my room. It was a single room, tidy, white tiles, one bed. The evenings were the worst. I was scared. Lonely. I can hardly remember the other children but was well aware of a teenager with a leg affected by polio. At night, I could hear him walk in his leg brace. I thought he was coming to my room to harm me.

The first day of school was awful. There was a huge Dutch Reformed Church that you had to pass, down some stairs and then to the school. The church was a mountain and had an ominous feel. Little interested me at school. I missed my mom and longed for all the people at the boarding house. I blocked out the world and stopped talking altogether.

On Friday evenings, they showed movies. Everybody around me laughed, but we were the throwaway people. The nothing people. Tannie Prins became worried about this mute, silent boy. After a while, she asked me if I would join her for a weekend visit to her parents. We drove there in silence. I have a hazy memory of her parents and the house, but what does stand out is that there was a dog that had given birth to a litter. I walked towards these tiny animals and stroked them. At that moment, I started talking. Words came back to me. I cannot remember what I said. But I thawed and started feeling like a person again and not like an empty shell, or a thing from outer space.

Years later, when Tannie Prins (as I still call her) and I met again, she told me that that weekend was also a tipping point for her parents. They couldn’t understand why she wanted to work in an orphanage. The stigma attached to children’s homes was enormous. But after they saw me transform from a wordless child to one who could talk and even laugh again, they changed their minds. They noticed her kind interaction with a small child and realized that her work had value. She gave love to children who felt unloved.

Although the orphanage was a haven, and even if they looked after us and took us on outings, served us meals and tried to create some warmth, I wanted my mother. It was a yearning that traumatised me to such an extent that, in later years in therapy, my psychologist diagnosed that little discarded boy as my primal wound.

The fallout was permanent: bad self-image, vicious outbursts of anger, sharp tongue, inferiority complex, imposter syndrome, endless feelings of melancholy and a fear of rejection. I learnt through years of psychoanalysis to manage these emotions, but they’ve never left me. Even if you achieve success, you feel hollow. Every day, I feel as if something terrible is going to happen; even more horrific, that nobody will be there to catch me when I fall. There is a label for that feeling of ennui and cynicism, for that void: it’s called Peggy Lee syndrome. Peggy Lee sang the song ‘Is That All There Is?’ Even if you succeed in something, you feel, ‘Is that all there is?’ It is a dreadful condition, but you soldier on. Naturally, there are highlights, tight and important friendships, a life fully lived, but the barrenness remains. I often feel invisible, even to myself.

My mother phoned once a week. I found the short conversations with her more depressing than uplifting because I knew the call would end. Her voice would be gone. I would be alone again. We could not say goodbye. Instead, we would say ta-ta to each other, up to twenty times. One of us had to put the phone down first. She didn’t want to, neither did I.

‘Okay, bye, okay bye, okay bye …’ On and on and on. Then poof. Gone. Certain weekends she could visit, but they weren’t many. She did not have transport and was dependent on friends. Sometimes she would let me know that she was coming, then I would stand on my bed to peer through the window into the car park to see if I could spot her. If I saw her, I would run outside, and she would wait for me. I would run into her arms. She would pick me up and swing me around and we would both cry. She usually packed coffee, biscuits and sandwiches in a little picnic basket.

Later on, I would stand on the bed every Sunday and stare into the car park. Staring at nothing. On the Sundays when she didn’t come, the pain was unbearable.

One day, I saved one of my mother’s sandwiches. At school we were given buttered white bread with red strawberry jam for lunch. To this day, I cannot stomach that jam. So, I thought that I would treat myself to a special sandwich one day and hid it in my cupboard. I took it to school in my suitcase and went onto the playground at break. When I bit into it, I found that I had kept it too long; it was covered in mould. I spat it out and cried; grief overwhelmed me. DM

Son of a Whore: A Memoir by Herman Lategan is published by Penguin Random House SA (R280). Visit The Reading List for South African book news, daily – including excerpts.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.