THE OUTLAW OCEAN PROJECT (PART ONE)

Death on the high seas — China, the seafood superpower, and the tragic story of Daniel

In recent decades, working aggressively to expand its might, China has transformed itself into the world’s seafood superpower. This pre-eminence has come at a grave human and environmental cost. This is Daniel’s story. This is Part One of this series.

MONTEVIDEO, Uruguay – In the early morning hours of 8 March 2021, a small inflatable boat powered by an outboard motor covertly made its way into the port of Montevideo to unload a dying deckhand, and then sped away.

The deckhand, a slight 20-year-old Indonesian named Daniel Aritonang, had been at sea for the previous year and a half, working on a Chinese squid-fishing ship called the Zhen Fa 7. Now he was dumped dockside, barely conscious, with two black eyes, bruises along the sides of his torso, and rope marks around his neck. His feet and hands were bloated, the size of melons.

Paramedics put Aritonang in an ambulance and rushed him to a nearby hospital. Jesica Reyes, a local interpreter, was summoned, and when she arrived she found Aritonang in the ambulance bay. He told her that he’d been beaten, choked and deprived of food for days. As doctors took him away to the emergency room, he began crying and shaking. “Please, where are my friends?” he asked her, and then whispered, “I’m scared.”

Montevideo, one of the world’s busiest ports, is popular among Chinese squid ships, several hundred of which in recent years have been targeting the rich high-seas fishery that lies off South America’s southeastern coast. The ships are drawn to Montevideo as an option for refuelling, making repairs and restocking, in part because the next-best options, in Brazil, Argentina and the Falkland Islands, are either too expensive or closed to them.

Many of the crew on Chinese ships are Indonesian, and when they arrive in Montevideo dead, injured or sick, port officials contact Reyes, who is among the only interpreters in the city who speaks Bahasa, Indonesia’s official language. She gets calls often to manage the families of dead workers. For most of the past decade, one dead body has been dropped off every other month on average in this port, mostly from Chinese squid ships.

Like all squidders, the Zhen Fa 7 is festooned with hundreds of bowling-ball-sized light bulbs, which hang on racks on both sides of the vessel and are used to lure squid up from the depths. 22 March 2022. (Photo: Einar Ollua | Esteban Medina San Martin)

In taking the job on the Zhen Fa 7, Aritonang had stepped into what may be the largest maritime operation the world has ever known. Fuelled by the world’s growing and insatiable appetite for seafood, China has dramatically expanded its reach across the high seas, with a distant-water fleet of as many as 6,500 ships, which is more than double its closest global competitor. China also now owns or runs terminals in more than 90 ports around the world and has bought political loyalties, particularly in coastal countries in South America and western Africa. It has become the world’s undisputed seafood superpower.

But China’s pre-eminence on the water has come at a high human and environmental cost. Fishing is ranked as the deadliest job in the world and, by many measures, Chinese squid ships are among the most brutal. Debt bondage, human trafficking, violence, criminal neglect, preventable injuries, and death are common in this fleet.

US labour officials say that China’s squid ships, which today make up the bulk of the country’s distant-water fishing fleet, are highly prone to using forced labour. They are also ranked as the largest purveyor of illegal fishing in the world. A 2022 review of illegal fishing incidents that occurred between 1980 and 2019, commissioned by the European Parliament, found that nearly half of the cases where the vessel type was identified were committed by squid ships.

Compared with other countries, China has been not only less responsive to international regulations and media pressure when it comes to labour rights or ocean preservation, but also less transparent about its fishing boats and processing factories, said Sally Yozell, the director of the Environmental Security Program at the Stimson Center, a research organisation in Washington, D.C. Since a large proportion of fish consumed in the US is caught or processed by China, she said, it is especially difficult for companies to know whether the products they sell are tainted by illegal fishing or human rights abuses.

For China, the vast armada has great value that extends beyond just maintaining its status as a seafood superpower. It also helps the country create jobs, make money, and feed its growing middle class. Abroad, the fleet forges new trade routes, flexes political muscle, presses territorial claims, and increases China’s political influence in the developing world.

“Plenty of countries are engaging in destructive fishing practices but China is distinct because of the size of its fleet and because it uses the fleet for geopolitical ambitions,” said Ian Ralby, CEO of I.R. Consilium, a global consultancy that concentrates on maritime security. “No one else has the same level of state ownership in this industry, no one else has a law that obligates their fishing ships to actively gather and hand over intelligence to the government and no one else is as actively invading other countries’ waters.”

***

The Zhen Fa 7 began its journey on 29 August 2019, when it left the port of Shidao, in China’s Shandong province, and sailed to the port of Busan, South Korea, to pick up its Indonesian crew.

It was a festive time. The final week of August marks the start of the autumn fishing season in China and sees more than 20,000 ships launch each year, destined for near and distant waters.

Amid fireworks and drum-playing, coastal villagers in Shidao hung red flags on fishing boats to celebrate hopes for a hearty haul. Three days after the Zhen Fa 7 launched, a celebratory headline in a provincial newspaper declared, “Open the sea! Let’s open our appetite and eat seafood”.

Daniel Aritonang had worked hard to secure a position on board. After graduating from high school in 2018 he had struggled to find work. The rate of unemployment in Indonesia was high: more than 5.5% nationally, and more than 16% for young people. Climate change has made matters worse as many of the country’s 17,000 islands are sinking. Aritonang’s home is roughly 100m from the Indian Ocean. His village is losing coast from sea level rise at an average of between 10m and 15m a year.

So, when Anhar, a local friend, suggested that the two of them go abroad together on a fishing boat, Aritonang agreed. Friends and family were surprised by his decision, because the demands of the job were so high and the pay so low. But a job was a job, and both he and Anhar desperately needed one. “On land, they ask for my skill.” Anhar said, recalling why he decided to go to sea. “To be honest, I don’t have any.”

In the summer of 2019 Aritonang and Anhar contacted PT Bahtera Agung Samudra, a “manning” agency based in Central Java. In the maritime world, manning agencies recruit and supply workers to fishing ships, handling everything from paychecks, work contracts and plane tickets to port fees and processing visas. They are poorly regulated, frequently abusive, and have been connected to human trafficking.

To discern what factories in China processed the Zhen Fa 7’s squid, reporters investigating Aritonang’s death hired investigators in China to conduct direct surveillance in 2022 in the port of Shidao. 11 September 2022. (Photo: The Outlaw Ocean Project)

On 5 July 2019, following the agency’s instructions, Aritonang and Anhar took a boat to Java and then made their way to Tegal. There they took a medical exam and handed over their passports and bank documents, along with several headshots and copies of their birth certificates. (PT Bahtera does not have a licence to operate, according to government records, and did not respond to requests for comment.)

For the next two months they waited in Tegal to hear if they got the job. Money ran short. Through Facebook messenger, Aritonang wrote to his friend Firmandes Nugraha, asking for help to pay for food. Nugraha urged him to return home. “You don’t even know how to swim,” Nugraha reminded him. Eventually, assignments came through, and, on 1 September, Aritonang appeared in a Facebook photo with other Indonesians waiting in Busan to board their fishing vessels. “Just a bunch of not high ranking people who want to be successful by having a bright future,” said Aritonang.

That day, Aritonang and Anhar boarded the Zhen Fa 7, and the ship set sail across the Pacific. They numbered 30 men: 20 from China and 10 from Indonesia.

***

The Chinese have established a remarkable presence on the world’s oceans during the past several decades. The effort began in 1985, when the China National Fisheries Corporation (CNFC) dispatched 13 trawlers carrying a crew of 223 men to work the coast of Guinea-Bissau in west Africa. A promotional video about the first fleet described the crew (“223 brave pioneers cutting through the waves”) as setting out on a 16,000km voyage to Africa that would take 50 days.

In launching the fleet, a military-run ceremony was held at the Mawei Port, in Fuzhou, Fujian Province, with more than 1,000 people in attendance, including Party elites. During the ceremony, a fishing-company executive explained that the purpose of the fleet was to promote goodwill abroad, show the world Chinese perseverance and hard work, and “strive for victory in their first battle”.

Connective tissue

Today, the CNFC, which is state-run, is the largest distant-water fishing company in the world, and the Zhen Fa 7, where Aritonang found himself, is one of the hundreds of fishing ships that supply the company. The CNFC forms the connective tissue for much of the industry, including many of the worst scofflaw ships. It owns more than 250 fishing boats and refuel ships, and at least six seafood processing plants or cold storage warehouses, and more than 15 refrigeration vessels, or reefers, that carry the catch back to shore.

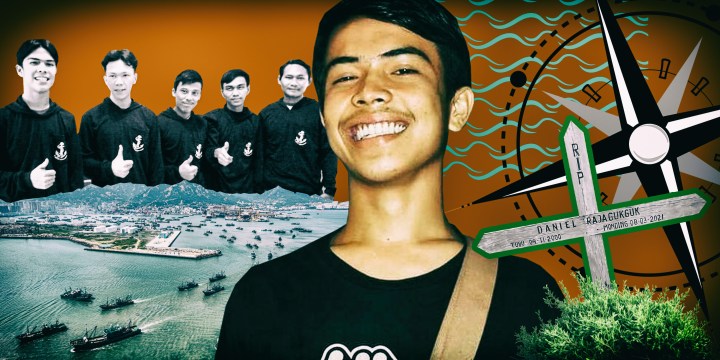

Daniel Aritonang, Hengki Anhar, and other Indonesians who worked on the Zhen Fa 7 were recruited by a manning agency called PT Bahtera Agung Samudra. 30 August 2019. (Photo: Facebook / Ferdi Arnando)

Daniel on a stretcher with an abdominal wound. (Photo: Supplied)

For most of the 20th century, distant-water fishing was dominated by three countries: the Soviet Union, Japan and Spain. These fleets shrank in size after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989 and as rising labour and environmental standards made it costlier for Japan and European countries to compete in the international seafood market. But during this period China sent more ships out across the globe, and those ships caught more seafood. China invested billions of dollars in its fleet and took advantage of new technologies – along with the Soviet Union’s decline – to muscle in on a very lucrative industry. China has also attempted to fortify its autonomy by building its own processing plants, cold-storage facilities and fishing ports overseas.

Those efforts succeeded beyond any predictions. China has now become the world’s undisputed seafood superpower. In 1988 it caught 198 million pounds of seafood; in 2020 it caught five billion. No other country even comes close.

Not all Chinese fishing vessels actually fish. Instead, hundreds of them serve as a kind of civilian militia that works to press territorial claims against other nations.

Political analysts, particularly in the West, say that having just one country controlling a global resource as valuable as seafood creates a precarious power imbalance. Navy analysts and ocean conservationists also fear that China is expanding its maritime reach in ways that are undermining global food security, eroding international law and heightening military tensions. American officials are especially concerned – and prone to stoking international alarmism on the matter – because the US is in a trade war with China. The US is also the world’s largest importer of seafood, with China as its largest supplier.

Ian Ralby, the CEO of I.R. Consilium, a maritime-security research firm, said that through its distant-water fishing fleet, China is working to establish de facto sovereignty over international waters, by leaning on a terrestrial legal concept called “adverse possession”, which, in essence, grants property rights to anyone who occupies and controls an area long enough.

The concept is akin to “squatter’s rights” – the notion that possession constitutes nine-tenths of the law. The recent signing by 193 countries of a high-seas biodiversity treaty, which aims at eventually protecting 30% of the world’s oceans, is unlikely to change China’s course.

“China likely believes that, in time, the presence of its distant-water fishing fleet on the high seas will convert into some degree of sovereign control over those waters and the resources in them,” Ralby said. “With 70% of the Earth covered in water, any one state’s effort to establish rights and interests over the global commons should be a concern.”

According to Greg Poling, a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, there’s another wrinkle in all of this: Not all Chinese fishing vessels actually fish. Instead, hundreds of them serve as a kind of civilian militia that works to press territorial claims against other nations. Many of those claims concern seafloor oil and gas reserves. Taking ownership of the South China Sea, for example, Poling said, is part of the same historical project for the Chinese as taking control of Hong Kong and Taiwan. The goal is to reclaim “lost” territory and restore China’s former glory.

***

China’s dominance has come at a moment when the world’s hunger for products from the sea has never been greater. Seafood is the world’s last major source of wild protein and an existentially important form of sustenance for much of the planet. During the past 50 years, global seafood consumption has risen more than fivefold, and the industry, led by China, has satisfied that appetite through technological advances in refrigeration, engine efficiency, hull strength and radar. Satellite navigation has also revolutionised how long fishing vessels can stay at sea, and the distances they travel.

Industrial fishing has now advanced technologically so much that it has become less an art than a science, more a harvest than a hunt. To compete requires knowledge and huge reserves of capital, which Japan and European countries have in recent decades been unable to provide. But China has had both, along with a fierce will to compete and win. Its “Going Out” policy, launched in 2001, energetically encouraged Chinese companies to expand their presence abroad, backed by state money.

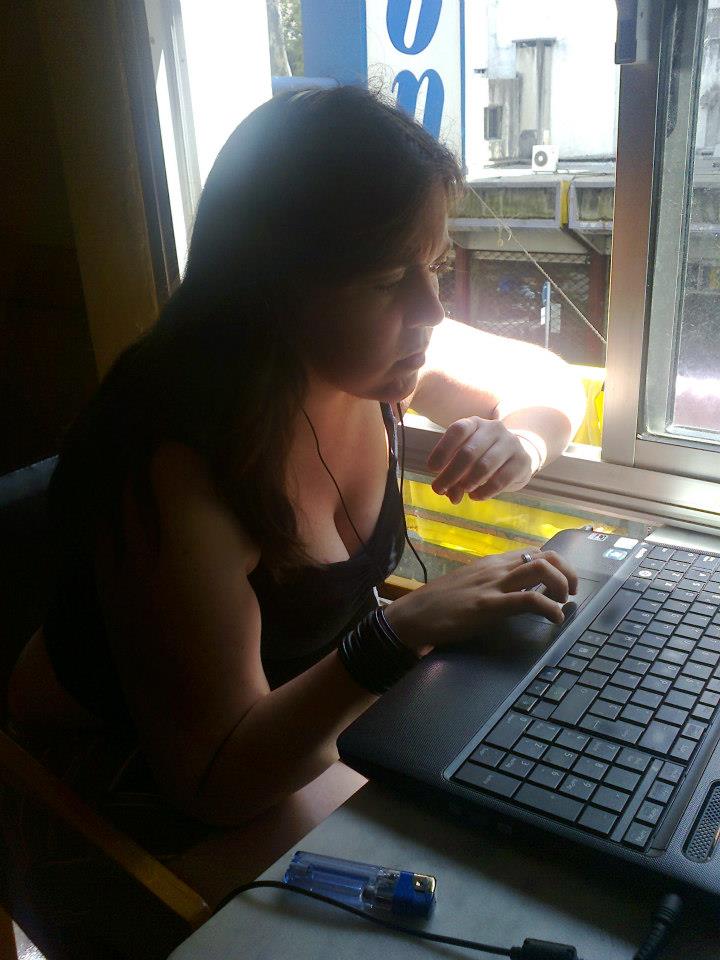

Jesica Reyes, one of the only Bahasa interpreters in Montevideo, Uruguay, gets calls often to manage the families of dead workers. 26 February 2013. (Photo: Facebook / Jesica Reyes)

Bolstered fleet

China has grown the size of its fleet predominantly through state subsidies, which by 2018 had reached $7-billion annually, making it the world’s largest provider of fishing subsidies. The vast majority of that investment went towards expenses such as fuel and the cost of new boats. Ocean researchers consider these subsidies harmful, because they expand the size or efficiency of fishing fleets, which further deplete already diminished fish stocks.

The Chinese government’s support of its fleet is vital. Enric Sala, the director of National Geographic’s Pristine Seas project, said that more than half of the fishing that occurs on the high seas globally would be unprofitable without these subsidies, and squid jigging is the least profitable of all types of high-seas fishing.

China bolsters its fleet with more than $7-billion a year in subsidies, as well as through logistical, security, and intelligence support. For example, China sends its squid-fishing vessels a weekly digital index that provides updates on the size and location of the world’s major squid colonies. This helps them decide when and where to chase their catch, and often means that they work in a coordinated manner.

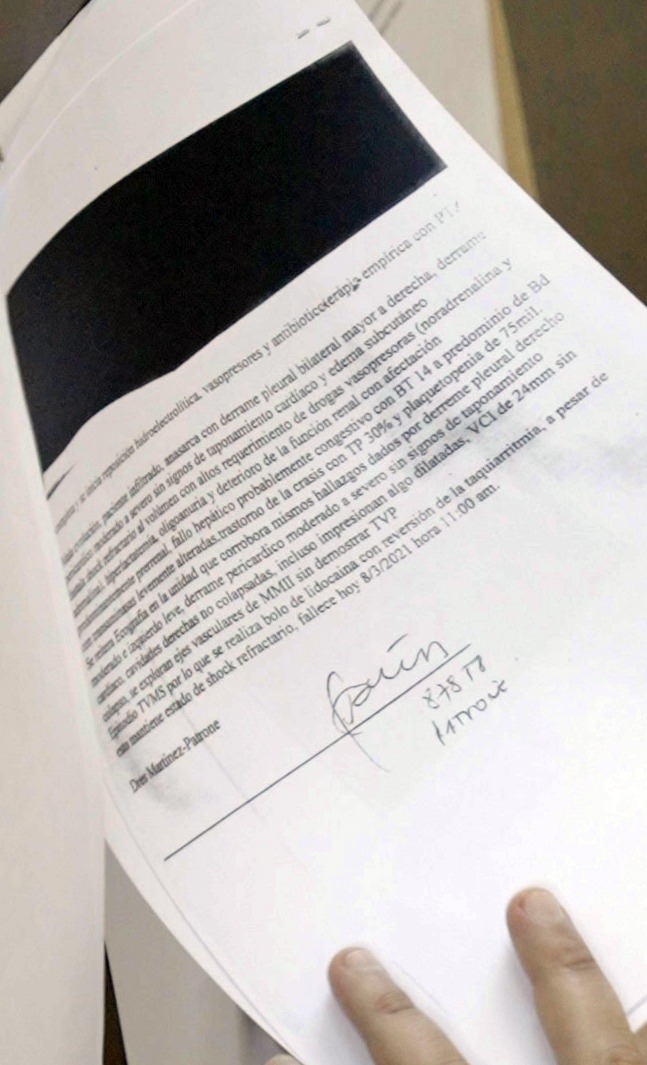

The autopsy report noted that Aritonang’s face and extremities were swollen. 8 March 2022. (Photo: The Outlaw Ocean Project / Ed Ou)

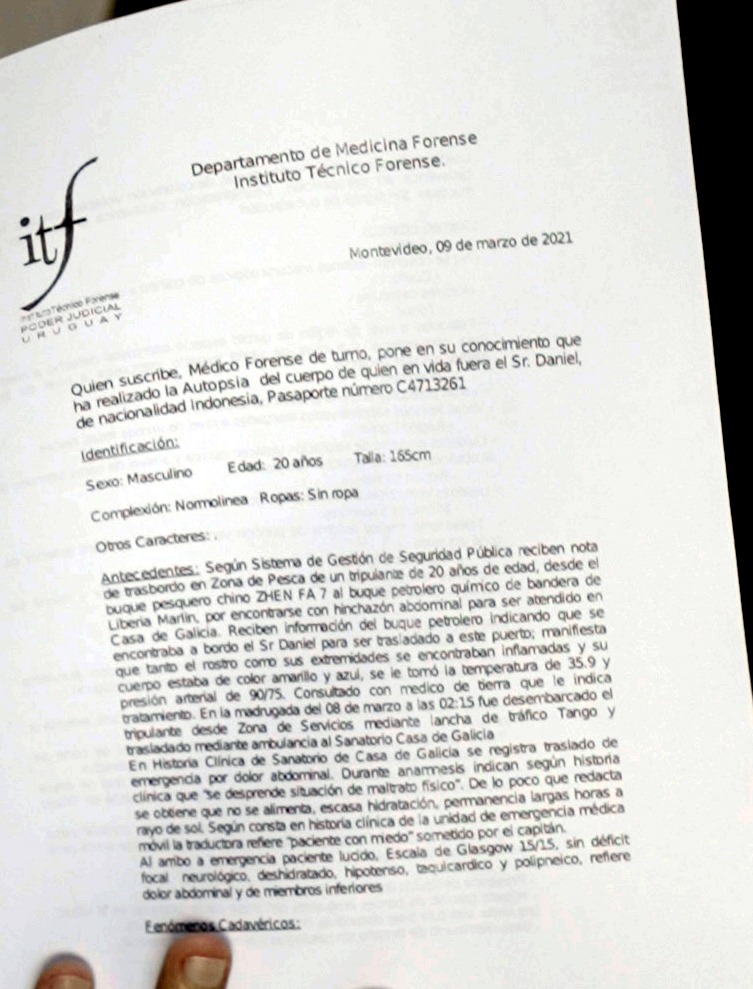

A local medical examiner conducted an autopsy on Daniel Aritonang the day after he died, but did not offer an official cause of death. 8 March 2022. (Photo: The Outlaw Ocean Project / Ed Ou)

In July 2022, a reporter shadowed a group of about 260 Chinese squid ships that were jigging a patch of sea 340 miles west of the Galapagos Islands. Part of this fleet was the Zhe Pu Yuan 98, a squid ship that doubles as a floating hospital and is equipped with two doctors, an operating room, a specialised machine for running blood tests, and remote video-conferencing capabilities for consulting with doctors back in China.

“When [crew members] are sick, they will come to our ship,” the captain told the reporter over the radio. “We help cure them.” Capable of staying at sea for a year, the ship was funded by fishery authorities in the port city of Zhoushan. At one point during the trip, the reporter watched as the bulk of the fleet suddenly pulled up anchors, in near simultaneity, and moved together to a location roughly 115 miles to the southeast. “This kind of coordination is atypical,” Ted Schmitt, the director of Skylight, a maritime-monitoring programme, told me. “Fishing vessels from most other countries wouldn’t work together on this scale.”

***

By December 2019, the Zhen Fa 7 had crossed the Pacific and was fishing near the Galapagos Islands. It would spend the next two months chasing squid in international waters off the west coast of South America.

The fishing grounds near the Galapagos are one of several major open-ocean regions that the Chinese squid fleet routinely targets, including another in the South Atlantic Ocean, near the Falkland Islands, and a fishery in the Sea of Japan, in Korean waters.

Many of the details in this story come from reporting trips made to these regions between 2019 and 2022. One of those trips, facilitated in February 2022 by Sea Shepherd, an ocean-conservation group, included an invitation to board a Chinese squid-fishing ship that was fishing in the Blue Hole, an immensely productive high-seas squid fishery in the South Atlantic, near the Falklands. The captain of the vessel, which had a crew of 31 and was similar in size to the Zhen Fa 7, granted reporters permission to roam freely as long as they did not name him or his vessel.

Zhe Pu Yuan 98 is a squid ship that doubles as a floating hospital. 9 July 2022. (Photo: The Outlaw Ocean Project / Ben Blankenship)

Watery purgatory

The mood on board felt like that of a watery purgatory. The ship had about 50 “jigs” hanging off each side, each operated by an automatic reel. Crew members stationed around the deck were responsible for monitoring two or three reels at a time, to ensure they didn’t jam. The men’s teeth were yellowed from chain smoking, their skin a sickly sallow, their hands torn and spongy from sharp gear and perpetual wetness. Most wore thousand-mile stares as they babysat their equipment, their expressions recalling a quote from the Scythian philosopher Anacharsis, who famously divided people into three categories: the living, the dead and those at sea.

To avoid the chef, who seemed to hit him especially often, Kusmanto skipped meals and only ate white rice, which he could serve himself during off hours.

The crew on these ships, foreign and Chinese alike, routinely discover after they have begun their journeys that the pay is not what they were promised, the length of time at sea is far greater than they had realised, and the conditions are far worse than they imagined.

According to a report released in 2020 by the US Department of Labour, Chinese squidders rely heavily on migrant and captive labour. The situation is particularly dire for Indonesians. When the Environmental Justice Foundation interviewed 116 Indonesian crew members who had worked between September 2020 and August 2021 on Chinese distant-water vessels, roughly 97% of them reported having experienced some form of debt bondage or confiscation of guaranteed money and documents, and 58% reported having seen or experienced physical violence.

***

Alongside Aritonang on the Zhen Fa 7 was another Indonesian named Heri Kusmanto, who fell sick in June 2020. His legs and feet swelled and became achy. Listless, he lost his appetite and ability to walk. The Indonesians on board speculated that the cause was his eating too many noodles and drinking dirty water, but in all likelihood he was suffering from a disease known as beriberi, caused by a deficiency of vitamin B1, also known as thiamine.

Sometimes called “rice disease”, beriberi has historically broken out on ships and in prisons, asylums, and migrant camps – anywhere that diets have consisted mainly of polished or white rice or wheat flour, both very poor sources of thiamine. When beriberi happens on ships, it is considered a possible indicator of criminal neglect because it is slow-acting, treatable and reversible, according to forensic pathologists.

In the final week of August 2022, China’s fishing season begins with thousands of vessels leaving simultaneously to begin their work. August 2022. (Photo: Dazhong Daily)

Kusmanto had been a frequent target of violence on board. His job was to carry heavy and full baskets of squid from the upper deck down to the refrigerated hold. But he often made mistakes, which spurred the wrath of Chinese officers, who beat him. “He did not dare fight back,” recounted Fikran, another of the Indonesians. To avoid the chef, who seemed to hit him especially often, Kusmanto skipped meals and only ate white rice, which he could serve himself during off hours.

The Indonesians began lobbying the captain to let Kusmanto off the ship, even though the contract used by his manning agency included heavy financial penalties for him and his family if he quit prematurely – a provision, among several others in the contract, that labour experts say directly violates anti-trafficking laws in the US and Indonesia.

Mostly, Chinese officers and the bosun slapped or punched the Indonesian deckhands for mistakes, sleights, or slowness. Sometimes other Chinese deckhands joined in and the beatings escalated to kicking or stomping on the victim.

The captain’s quarters were situated on high. Officers slept on the floor below him, and the Chinese deckhands under that. The Indonesians occupied the bowels of the vessel. Aritonang lived with five others in a room crisscrossed by clotheslines drying socks and towels, and strewn with liquor bottles. The captain issued each Indonesian two boxes of Supermi instant noodles per week for free. The cost for additional snacks, coffee, alcohol or cigarettes was deducted from their salaries. The Indonesians were paid $250 per month, along with a $20 bonus per tonne.

Whenever the Zhen Fa 7 was fishing for squid, the heaviest labour happened at night, from 5pm until 7am, in a cycle of six hours on, six hours off. But it didn’t happen in the dark. Like all squidders, the ship was festooned with hundreds of bowling-ball-sized light bulbs, which hung on racks on both sides of the vessel and were used to lure squid up from the depths.

As squid were hauled in, the scene on deck often looked like a brightly lit auto-body shop where an oil change had gone terribly wrong. When pulled onboard, squid squirt purplish black ink. Warm and viscous, the ink coagulates within minutes and coats all surfaces with a slippery, mucus-like ooze. Because deep-sea squid have high levels of ammonia in their tissue, for buoyancy, the air on board smells powerfully like urine.

Crew aboard the Zhen Fa 7 hold up a large squid. They numbered 30 men: 20 from China, and the remaining 10 from Indonesia. 7 July 2021. (Photo: Facebook / Ferdi Arnando)

Aritonang on the bridge of the Zhen Fa 7. 7 July 2021. (Photo: Facebook)

Violence on board was common. Mostly, Chinese officers and the bosun slapped or punched the Indonesian deckhands for mistakes, sleights, or slowness. Sometimes, though, other Chinese deckhands joined in and the beatings escalated to kicking or stomping on the victim until other Indonesians intervened.

In July, as Kusmanto’s health worsened, the Zhen Fa 7 went dark on six separate occasions, turning off its transponder in violation of Chinese law and disappearing from tracking for as long as 16 days. Ship captains often turn off their transponders to fish illegally and undetected in waters, like those of Ecuador, where Chinese ships are typically forbidden. That the vessel went dark whenever it was closest to Ecuadorian and Peruvian sea borders, sometimes just a half dozen miles from the line, is an indicator that the ship was likely engaging in illegal activity, according to research compiled by the US embassy in Quito.

In December 2020, the Zhen Fa 7 left the vicinity of the Galapagos Islands, sailed around the southern tip of South America, through the Strait of Magellan, and made its way north to the Blue Hole, about 360 miles above the Falkland Islands. The bounty was plentiful there, and the captain began working his crew around the clock. Aritonang fell severely ill in late January with beriberi, the same illness that Kusmanto had suffered from. The whites of his eyes turned yellow, his legs and feet grew swollen and achy, and he lost his appetite and ability to walk.

The other Indonesians on board begged the captain to get Aritonang onshore medical attention, but the captain refused. Later, when asked to explain the captain’s refusal, Anhar, Aritonang’s friend and fellow crewmate, said: “There was still a lot of squid. We were in the middle of an operation.”

By February, Aritonang could no longer stand. He moaned in pain, slipping in and out of consciousness. Incensed, the Indonesian crew threatened to strike. “We were all against the captain,” Anhar recounted. The captain finally acquiesced on 2 March and had Aritonang transferred to a nearby fuel tanker called the Marlin, whose crew six days later dumped him off in Montevideo. But by then it was too late. For several hours, the emergency room doctors struggled to keep him alive, while Reyes waited anxiously in the hall.

Eventually they emerged from the emergency room to tell her that he had died.

A day later, the local coroner conducted an autopsy. “A situation of physical abuse emerged,” it reads.

Nicolas Potrie, who runs the Indonesian consulate in the city, recalls getting a call from Mirta Morales, the prosecutor who investigated Aritonang’s case, who told him: “We need to continue trying to figure out what happened. These marks – everybody saw them.” Morales declined to say whether the investigation was closed but added that, as with most crimes at sea, she had very little information to work with.

***

On 22 April, Aritonang’s body was flown from Montevideo to Jakarta, and the next day it was driven by ambulance to his family home in the countryside, where a solemn crowd of villagers lined the road to pay their respects. Fatieli Halawa, the village pastor, recalled how Aritonang’s mother wailed then fainted on seeing the shiny wooden casket with a Jesus figurine on top. Aritonang’s province is more than 95% Muslim, but he was a Christian, and had attended mass weekly. The family opted not to open the coffin.

After graduating from high school in 2018, Daniel Aritonang struggled to find work until a friend suggested they go abroad on a fishing boat. 27 September 2018. (Photo: Instagram)

A wooden cross marks the grave of Daniel Aritonang Rajagukguk, on the outskirts of the Indonesian village of Batu Lungun. 9 April 2022. (Photo: The Outlaw Ocean Project / Sihkami Denting)

‘Peace agreement’

A funeral was held the next day, with roughly 75 people in attendance. The afternoon was warm and humid. Aritonang was buried a few feet from his father, in a cemetery plot not far from his church, near the side of a road. His grave marker consisted of two slats of wood joined to make a large cross, on which appeared his name, the dates of his birth and death, and the letters RIP.

That night, an official from Aritonang’s manning agency visited the family at their home to discuss a “peace agreement”. Anhar said the family ended up accepting a settlement of 200 million rupiah, or roughly $13,000. The family was reluctant to talk about the events on the ship. Aritonang’s brother Beben said he didn’t want his family to get in trouble, and that talking about the case might cause problems for his mother.

“We, Daniel’s family,” he said, “have made peace with the ship people and have let him go.”

More than 9,000 miles away, the Zhen Fa 7 soon began its long journey home. In May 2021, it reached Singapore, where it disembarked its remaining Indonesian crew, who had not stepped on land for nearly two years. The ship then at last returned to Shandong where it unloaded 330 tonnes of squid, marked in port records as destined for export.

To discern what factories in China processed the Zhen Fa 7’s squid, reporters investigating Aritonang’s death hired investigators in China to conduct direct surveillance in 2022 in the port of Shidao, in Shandong province.

Aritonang’s family home underwent repairs after his death, using money from the settlement, according to the village chief. 10 April 2022. (Photo: The Outlaw Ocean Project / Sihkami Denting)

The investigators filmed a refrigeration ship in port that had just months before taken catch from the Zhen Fa 7. Through much of the night, men in blue jumpsuits used forklifts to load hundreds of the Zhen Fa 7’s bags of frozen squid into trucks. The investigators then trailed the trucks to their processing plants. With knowledge of the processing plants that were being used, it became possible to turn to export-import records for the sake of pinning down the European and American buyers of the squid.

Through export records, satellite tracking and direct surveillance in Shidao port, we connected the Zhen Fa 7 to at least six processing plants in China that export large volumes of squid to US importers.

These importers supply seafood to retailers, dining chains and food-service companies, including Kroger, Costco, H Mart, Safeway and Performance Food Group. All of these companies, except one, declined to respond to questions about their seafood supply and ties crimes, including those on the Zhen Fa 7.

Read more in Daily Maverick: The Lawless Oceans — forced labour on rust-bucket boats docking at Cape Town harbour

In an email, the Zhen Fa 7’s owner, Rongcheng Wangdao Ocean Aquatic Products Co. Ltd, declined to comment on Aritonang’s death but said it had found no evidence of complaints from the crew about their living or working conditions on the vessel. The company added that it had handed the matter over to the China Overseas Fisheries Association, which regulates the industry. Questions submitted to that agency went unanswered.

On 10 April 2022, a year after Aritonang’s death, his mother, Sihombing, sat on a leopard-print rug in her living room with Leonardo, her other son. Sihombing apologised that it had no furniture, and no place other than the floor to offer a guest to sit. The house underwent repairs, using money from the settlement, according to the village chief; in the end, Aritonang had managed to fix up his parents’ house after all.

Asked about Daniel, Sihombing began to weep. “You can see how I am now,” she finally mustered.

“Don’t be sad,” Leonardo said, patiently trying to console his mother. “It was his time.” DM

This story was produced by The Outlaw Ocean Project, a nonprofit journalism organisation in Washington, D.C. Reporting and writing was contributed by Ian Urbina, Joe Galvin, Maya Martin, Susan Ryan, Daniel Murphy and Austin Brush. This reporting was partially supported by the Pulitzer Center.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.