COUP D’ETAT OP-ED

‘Coupnomics’ and endangered democracies — there is no such thing as a ‘good’ coup

The cornerstones of a robust democracy are strong institutions, good governance and transparency. An attack on democracy in one country should be seen as an attack on democracy in all countries.

In 2011, The Economist and others championed the “Africa Rising” narrative, highlighting improved governance, rising incomes, and a growing middle class. These changes marked a shift away from instability and coups, a common occurrence in the 1960s and 1980s.

However, the 2020s mark a return to the era of coups, with The Economist cautioning now that the frequency of coups in this decade could surpass that of the 1960s. Since 2017, there have been 18 coups globally — all have occurred in Africa except for one, the 2021 coup in Myanmar.

Similarly, since 2013, at least 20% of African countries have experienced this spate of coups. The root causes of these unconstitutional takeovers never disappeared. Democratic institutions across Africa have remained weak or absent. Transparency, inclusive governance, and accountability continue to decline, with several African leaders overstaying their terms and flaunting their wealth amidst widespread poverty, often due to poor governance.

However, debates should not be framed around whether these are good coups or bad coups; instead, the political economy of coups, or what we term “coupnomics” and its implication for democratic decline must be explored. The resurgence of coups and the ensuing “coupdemic” across the so-called “coup belt” mirrors the democratic backslide witnessed across the continent in recent years.

Furthermore, the potential for this trend to extend beyond the “coup belt” — a region encompassing West and Central Africa, including the Sahel — is becoming an increasingly tangible threat.

An injured man is carried through a crowd during a Day of Resistance demonstration on 13 November, 2021 in Omdurman, Sudan. In Sudan, three weeks after the coup led by Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, civil society organizations called for civil disobedience and a general strike. (Photo: Abdulmonam Eassa/Getty Images)

Read more in Daily Maverick: Crackdowns on corruption, service delivery focus — how Africa can end its rash of military coups

To stem the contagion, scholars and policy practitioners must ask two fundamental questions: first, why has democracy begun to decline on the continent? And, second is the qui bono question — who benefits from Africa being engulfed in an enduring cycle of pestilence?

Failing economies, failing institutions

There are several internal and external factors that trigger coups. The UNDP’s Soldiers and Citizens report comprehensively analyses the triggers that could potentially incite coup risks. One clear thing is that a strong democracy with robust institutions reduces the risk of coups.

However, according to the Mo Ibrahim Foundation, Africa began its democratic decline a decade ago, thanks to rampant corruption and mismanagement, eroding institutional integrity. Even countries like South Africa and Ghana, known for their democratic values, have experienced a degree of “democratic deconsolidation”, leading to public protests against governance issues.

An escalating cost-of-living crisis has further exacerbated the situation, a problem significantly amplified by the Covid-19 pandemic. The economic fallout from the pandemic has placed additional strain on already struggling economies across the continent.

Corruption was cited as the reason for the coups in Mali and Guinea. However, despite growing discontent, many African leaders still act with impunity. For instance, Teodoro Obiang, the vice president of Equatorial Guinea (and the president’s son), took to social media to show off spending $75,000 a night for a penthouse in New York at a time when their country had a begging bowl in hand at the UN General Assembly. This is in spite of the fact that 70% of the citizens of Equatorial Guinea live in dire poverty. Moreover, controversial elections in Gabon, Central African Republic, Nigeria and Zimbabwe are precursors to political instability.

Niger President Mohamed Bazoum was deposed in a coup in July 2023. (Photo by Yves Herman – WPA Pool/Getty Images)

In the face of contamination, the African Union (AU) and the regional economic communities have been anaemic in their response. They have been inconsistent in response to the recent spate of coups.

Moreover, they have been slow to take their peers to task for illegitimate elections or attempts at constitutional amendments to extend presidential term limits. The default mode of congratulating incumbents who have won fraudulent elections reinforces resentment and disenchantment of the populace. It also diminishes the legitimacy of regional institutions as neutral and progressive actors in the democratisation ecosystem. In essence, regional institutions have paid little or no attention to early wearing signs of factors that invariably lead to instability.

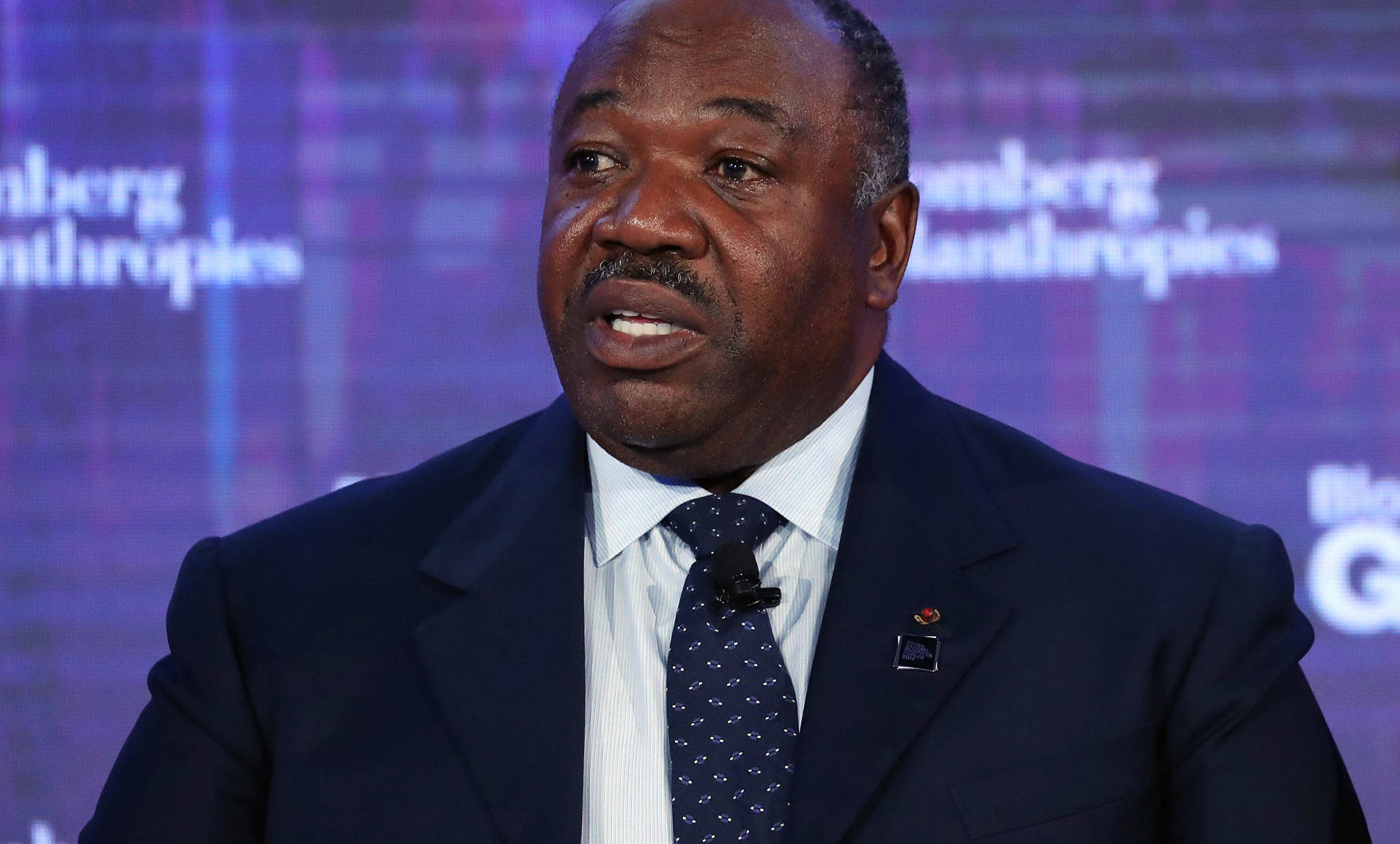

Former President of Gabon, Ali Bongo Ondimba, was overthrown from government on 30 August, 2023. (Photo: EPA-EFE/Andrew Gombert)

Read more in Daily Maverick: Eswatini faces perilous future under Mswati despite elections monitoring thumbs-up from AU, SADC

Read more in Daily Maverick: Zim activists slam Ramaphosa’s ‘premature’ endorsement of poll result, urge him to take action amid ‘abductions, killings’

‘Coupdemics’: The (good?) business of coups

Acknowledging the intricate interplay between political economy and the phenomena of crises and coups is also crucial. The emergence of insecurity caused by a dying or non-existent democracy gives rise to a parallel economy, as evidenced by the proliferation of private military operations, the expansion of security assistance programmes, and the exploration of alternative avenues by military personnel to safeguard their financial interests. This underscores the complex dynamics of conflict and power transitions in the political economy.

One current argument is that private military assistance, particularly from the US, is behind the recent spate of coups. Increased security assistance by Western powers such as the US, EU, and Canada and newer players such as Russia and China have exposed severe shortcomings in Washington’s approach to the region.

Members of the Movement of June 5, known as Rassemblement des Forces Patriotiques (M5-RFP) group, clash with police who used tear gas to disperse the crowd ahead of the next round of national consultations on the management of the transition in Bamako, Mali, on 10 September, 2020. (Photo: EPA-EFE / H Diakite)

The rhetorical and political emphasis Washington has placed on counterterrorism can risk securitising local politics and elevating the political saliency of military leaders over their civilian counterparts. However, as those against this view point out, there is more to the picture than meets the eye, considering the number of actors involved.

Security assistance programmes, such as military training and access to sophisticated equipment and weaponry, have changed the security marketplace fundamentally. Military assistance and training exercises are a cornerstone of modern military relations, with countries like Brazil and Kenya undertaking joint exercises in the DR Congo and Morocco launching Africa Lion 2023 alongside Africom, training exercises that saw 18 nations collectively train under the Africom umbrella.

Interestingly, five members of the new military junta in Niger were trained by the US army. Also, the head of the military junta in Mali is US trained. Yet, the amount of money involved and the possible introduction of normative values that may be oppositional to the receiver state could give would-be coup plotters the courage to attempt a takeover.

We also must recognise that security assistance is lucrative and often persists through illicit channels after a coup. Mercenaries and private military companies such asWagner, Caci, and Academi have become a part of Africa’s security ecosystem.

People rally in Niamey, Niger, on 1 October, 2023, a few days after the departure of the French ambassador from the country. The French president announced on 24 September that France would withdraw its ambassador and military personnel from the country. The French military was yet to leave the Niamey base. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Issifou Djibo)

Halting the ‘coupdemic’

The coup redux underscores that the foundational pillar for Africa’s stability and prosperity remains unsettled. The socioeconomic landscape, including the role of external actors, has seen little sustainable transformation over the past seven decades.

Inoculating African countries from the spread requires that the AU and regional economic communities take their mandate seriously. The cornerstones of a robust democracy are strong institutions, good governance and transparency. An attack on democracy in one country should be seen as an attack on democracy in all countries. There is no time like the present to rethink the dynamics of the AU anti-coup regime.

This requires paying more than lip service to early warning signs and symptoms. Recent coups in Africa are not in any way surprising, with observers pointing to the possibility of more coups. The same energy, if not more, directed to military coups should also be given to early warning signs of suppression of fundamental rights, rigging of elections and the illegal elongation of presidential terms.

Where the incumbent engages in bold-face electoral banditry, the AU and regional economic communities should treat such a regime as a usurper and beneficiary of a coup. Through this, regional institutions can enhance their relevance as important actors in preventing irregularities and being on the side of the masses. DM

Dr Odilile Ayodele is a Senior Research Specialist at the Human Sciences Research Council’s (HSRC) Developmental, Capable and Ethical State (DCES) division.

Professor Babatunde Fagbayibo is Professor of International Law at the University of Pretoria and a Visiting Senior Researcher at the Nordic Africa Institute (NAI) in Sweden.

Both write in their personal capacities.

Comments - Please login in order to comment.