SILICOSIS CASE

Gold-mining widows and their children are battling with trauma and poverty

A cash settlement has not made much difference to the lives of the families of the men who became sickly and died after many years of working underground in gold mines.

Mzawubalekwa Diya, who contracted silicosis during his time working underground in South Africa’s gold mines, died one winter morning in the arms of his wife and daughter in their rural Eastern Cape home.

Diya, who was from Etyeni, a village located high up the valleys of Bizana, was one of a group of former gold miners who were litigants in the silicosis class action brought against companies that operated 33 gold-mining companies in 2012.

The action was brought against the companies that operated in South Africa for negligence that led to hundreds of thousands of mineworkers contracting tuberculosis and silicosis.

Lawyers for Diya and his colleagues argued that the employers failed to provide adequate health and safety measures. This led to workers inhaling silica dust, which leads to lung diseases.

The lawsuit, which was settled out of court in 2018, covered workers employed on the gold mines between 12 March 1965 and the date of the commencement of the legal action.

Diya received a cash payout last year from the Tshiamiso Trust, which was set up to process and compensate qualifying former workers. But the payment has not made much difference to the family’s situation.

Diya’s widow, MaCetshwayo Diya (57), can’t stop crying. The horror of helplessly watching the life slip away from the man she married more than 30 years ago weighs down on her every minute. She and her daughter Nolinda (24), in whose arms her husband died, never received any trauma counselling.

The prospect of a future without an income frightens her and adds to her troubles. For now they are still surviving on the leftover groceries donated by neighbours and church members for Diya’s funeral. He died on 18 May in the house he had built from the class action settlement payout.

“The money made some difference because, before, we had no house. But we at least managed to build a house with some of it. What was left after that paid for his funeral. So right now our situation is very bad. We have nothing and I’m scared about what will happen to us in future,” MaCetshwayo said.

Knitting grass mats

Widow MaCeliswayo Diya (right), with her daughter Nolinda, has never received any trauma or emotional counselling for her husband’s death. (Photo: Lucas Ledwaba/Mukurukuru Media)

The widow, who is sickly and depends on chronic medication collected from the local clinic, is unemployed, as is Nolinda. Her son is in Durban struggling to survive on piece jobs. MaCetshwayo spends her days knitting grass mats, which she tries to sell in the nearby town of Bizana on social grant payment days, when the streets come alive with hawkers. But when night falls, she retreats to the emptiness of her room and weeps for her late husband and her children, who face a bleak future.

About 100km away in Lusikisiki, Nokukhanya Mguca sells fruit and vegetables in the bustling town’s taxi rank. Some days she goes home without having sold a single item.

Competition for clients is high in this town, where many who are not employed in the retail stores or government departments survive on the state’s welfare and work in the informal sector.

MaCetshwayo and Nokukhanya’s battle for survival is a struggle faced daily by thousands of widows and orphans of former gold-mine workers in the Eastern Cape, Lesotho and other areas in southern Africa that served as labour-forwarding areas for the mines.

After many years of working down the gold mines, earning a pittance and with little in terms of benefits, husbands and sons returned home with nothing, sick and just waiting to die.

The conditions have resulted in a generational curse of poverty, with children like Nolinda struggling to finish high school or to get qualifications that would give them a good chance of earning a better living.

The Diya family sold their three remaining cattle and sheep in 2016 to pay for Nolinda’s enrolment for an electrical engineering course. But when the funds were depleted, she was forced to drop out.

Her father tried to find temporary jobs, but he couldn’t hold one down because of his deteriorating health.

Though the lawsuit has raised the hopes of many families, the grim reality is that the cash payout they have pinned their hopes on since the legal battle began is unlikely to sustain them for long.

Like Bizana, the Lusikisiki area was one of the labour-forwarding areas for the gold mines upcountry on the Witwatersrand and Free State goldfields for the better part of a century.

Nokukhanya’s husband, Eric Mguca, also joined the trek up north to work on the mines when he was barely out of his teens. In 2005 he was sent back home, coughing and thin as a stick. He spent two weeks in hospital but was discharged as there was “nothing more that could be done”.

A short while later, he too died in the arms of his wife.

Packed into single-sex compounds

Through the years they were married they hardly spent time together – the migrant labour system stipulated that wives and children couldn’t join their husbands, who were packed into single-sex compounds on the mines for most of the year.

Mguca’s medical records indicate he had tuberculosis. His death certificate states he died from natural causes. “He left us nothing. When he came back home he was very sick. Even now we have no proper house. We have just a little three-room [house],” said Nokukhanya amid the bustle of the taxi rank.

She said her husband received only R12,000 from his provident fund and long service after working since the 1970s. The couple married in 1984.

Her three unemployed children also scramble for a living doing whatever they can around Lusikisiki. She put in a claim with the Tshiamiso Trust in 2021, but has been frustrated by a lack of feedback and progress.

“I don’t know where we stand with this [Tshiamiso Trust claim]. If we get a payment from my husband’s claim then I [will] be able to take my children to school. That way they can find jobs,” she said.

Diya’s fate was no different. In 2012 he was diagnosed with silicosis, an incurable lung cancer caused by long-term exposure to silica dust generated during gold mining.

Like many men from his part of the world, Mpondoland, he was recruited to join the mines at the age of 18 in 1978 through the Employment Bureau of Africa. In the book Broke & Broken: The Shameful Legacy of Gold Mining in South Africa by Leon Sadiki and Lucas Ledwaba, Diya is recorded speaking about his experiences underground: “There was so much dust down there that sometimes we couldn’t see each other.”

While Diya was away digging for gold in faraway lands, MaCetshwayo stayed home to raise their children.

“It was hard because we hardly had anything and he was gone to the mines most of the time. I had to do piece jobs like cooking for learners in schools around the village. I raised my children through struggle. Life was very hard,” she said.

After 27 years of toil, Diya was discharged from work in 2005 with a measly payout of R70,000. He had begun feeling sick a year earlier, coughing up blood and spending time in hospital. However, he was not told the reason why he was being laid off work.

MaCetshwayo was shocked when her husband returned home and told her he had been retrenched.

“Life was very hard. He came back from the mines with nothing. When he was still working, he would send us some money. It wasn’t much, but it was better than nothing. But when he came home [after being retrenched], life got much more difficult,” MaCetshwayo said.

Supposed to sacrifice a cow

There are few employment opportunities in Etyeni where Mzawubalekwa Diya lived with his family. His son has been forced to seek piece jobs in Durban while his daughter has stayed home to look after her mother who’s still observing traditional mourning rites for her husband. (Photo: Lucas Ledwaba / Mukurukuru Media)

She is still dressed in the navy blue doek, blouse and skirt that signify her status as a recently widowed woman. After a year’s period of mourning, the family is supposed to sacrifice a cow as part of a ceremony to mark the end of the mourning period. She is not certain where the money for this sacred ceremony will come from.

Her deep sobbing fills the cold silence of the house that has now become eerie and sorrowful.

“When the [silicosis class action] case was concluded, he was very excited. He had been praying all along and never lost hope,” MaCetshwayo said.

Diya was a deeply religious man, a devoted member of the Nazareth Baptist Church and also steeped in the Mpondo traditional values.

In line with these beliefs, he had planned to use some of the payout to conduct a thanksgiving ceremony to the gods for having answered his prayers for compensation.

But a month before the planned ceremony, he died. He used part of the money to build a house for his family and another portion to pay off debts.

Diya was buried in his homestead in line with Mpondo traditions. Every morning when MaCetshwayo opens the door to their home, she is met by the grim sight of her late husband’s grave.

“It breaks my heart,” she said, breaking down into deep sobbing. “I know that I would never go to bed hungry if the person lying here was still alive.” Mukurukuru Media/DM

Life has become even harder for Nokukhanya Mguca since her husband died from suspected silicosis in 2015. She is waiting for her claim for financial compensation to be processed by the Tshiamiso Trust. Mguca has resorted to selling vegetbales and fruit in Lusikisiki in the Eastern Cape to support herself and her family. Her children have had to drop out of school and seek alternative means of survival. (Photo: Lucas Ledwaba/Mukurukuru Media)

Silicosis trust reports progress, but miners’ lobby group raises concern

The Tshiamiso Trust has reported payouts of R808-million to 9,118 claimants during the financial year ending in February 2023. The trust was established in 2020 as part of the silicosis class action settlement agreement.

The trust, which held its annual general meeting (AGM) in August, confirmed an increase of more than 400% in payments to claimants, taking the cumulative total to R1-billion two years after claim lodgments began.

However, the Justice for Miners (JFM) campaign has raised concern about the “slow pace of processing payouts”.

“We are pleased to know that they are starting to pay out claimants. However, the process is very slow…

“They need to finalise their processes so that they can pay more claimants, including the widows, and start doing [benefit medical examinations] for the qualifying claimants,” said Ziyanda Manjati of the JFM in response to the outcomes of the AGM.

The CEO of the trust, Dr Munyadziwa Kwinda, said that by the end of the reporting period it had completed a total of 46,736 benefit medical examinations. Kwinda said that, through the Employment Bureau of Africa, the trust had managed to search archived service records for 4,366 individual mineworkers who are potential claimants not yet on the database.

The JFM further raised concern that “the financial advice for claimants which is in the trust deed is not adequately applied or rolled out” and “there is no trauma or other support offered”.

“They do not even inform claimants properly when the compensation is paid. There is no acknowledgement that the compensation is being paid for an illness that the claimant got on the mine nor any expression of concern or human care for what the claimants are going through while living with these illnesses.”

Kwinda explained that the abridged death certificates issued to families in most instances do not refer to the primary cause of death, rather indicating the manner of death, which is natural, unnatural or undetermined.

As a result, families are required to provide further documentation from the departments of Home Affairs and Health, which may provide more information on the cause of death. Mukurukuru Media/DM

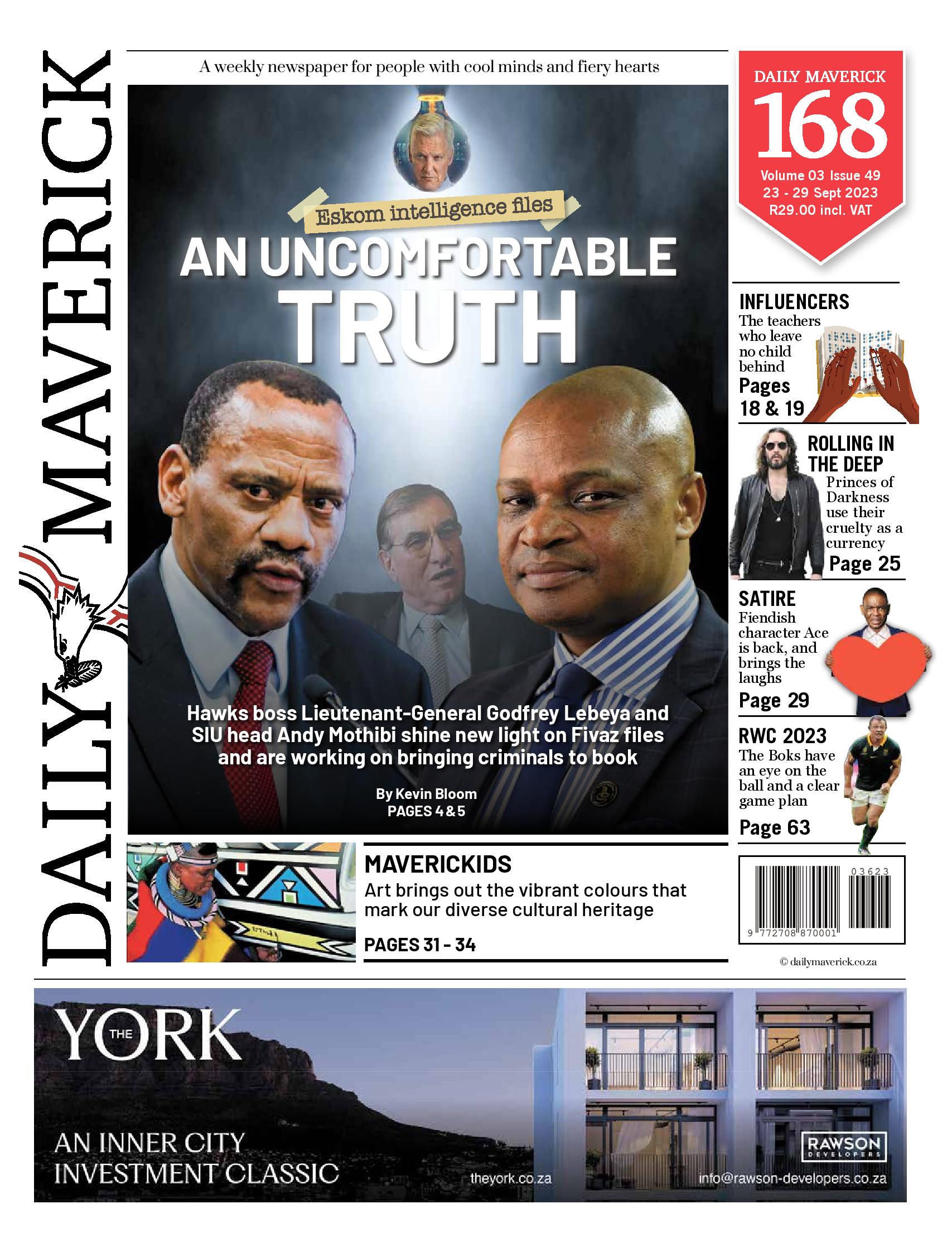

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper, which is available countrywide for R29.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.