BLUEPRINT FOR RECOVERY 2024

Part 5: Foreign policy after the BRICS Summit and Ukraine – making South Africa strong again

In 2017, Pravin Gordhan urged South Africa to ‘join the dots’ between corruption and the Zuma administration. John Matisonn joins those dots in this eight-part series. In this instalment, he spells out that, for too long, South Africa’s foreign policy has failed to prioritise its national interests and its constitutional values.

Also read Part 1, Part 2, Part 3 and Part 4.

Returning the country to domestic competence and effectiveness is the cornerstone of a country’s international position. Rebuilding abroad begins with rebuilding at home.

South Africa’s good name has taken a battering through State Capture, a trend which accelerated after it risked both its national interests and its founding values by soft-pedalling Russia’s brutal and illegal invasion of Ukraine, during which it displayed its military cooperation with Russia in a glare of hostile publicity.

We can no longer rely on our Mandela/Rainbow Nation laurels. We need a new vision for domestic rebirth alongside a coherent picture of the country we want to present to the world.

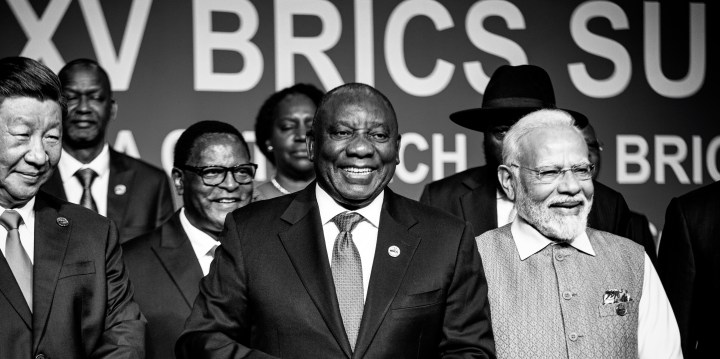

President Cyril Ramaphosa’s Ukraine peace mission and successful BRICS Summit management have navigated us back from the brink, but the malaise runs deeper.

South Africa’s foreign policy has for too long failed to prioritise both our national interests and our constitutional values. We cannot cut ties with countries whose practices we do not like, but we must manage our affairs in a way that we can hold our heads high, by not staying silent in the face of egregious violations of international law, and assiduously advance our interests in job-creating growth, national security and a stable world order.

To achieve this we need the support of multiple partners and the respect of the international community, both in the Global South and in pro-western democracies.

South Africa’s foreign policy should be built around a vision of our role in southern Africa, Africa, the Global South and the democracies. To do this requires a more thoughtful appreciation of global currents that affect South Africa and our continent, including the role of Russia and China in Africa, as well as France and other former colonial powers, their risks as well as their benefits.

Ramaphosa’s peace mission to Ukraine and Russia, and his first-rate hosting of a consequential BRICS Summit, have helped shore up South Africa’s fragile reputation.

Still, the government should never have allowed ambiguity in its opposition to Russia’s invasion, a fundamental violation of the UN charter and international law, and should call for its immediate and complete withdrawal from all occupied territories.

This will help revive South Africa’s reputation as a bastion of world peace and constitutionalism, which was tainted by our Russia stance. It will also go a long way towards healing the rift with the EU, US, Japan and other democracies that are among South Africa’s biggest trading partners and aid donors.

This matter remains critical, as sentiment in the EU and other Western countries with high investment and trade with South Africa has been turning negative. Unlike South Africa’s minimal trade with Russia, this trade is dominated by high value exports, which is most valuable for job creation and growth.

EU imports from South Africa are coming under scrutiny, and in Washington the Congress will review South Africa’s benefits from the African Growth and Opportunity Act (Agoa) in 2025, and removal of South Africa from the list will cost thousands of South African jobs.

Congress decides independently of the recent decision by the Biden administration to keep South Africa in Agoa this year. If the US Congress acts against us at the time of renewal, it will take South Africa years to recover from the symbolic and material damage if our Russia policy is the cause.

Of all the significant countries we deal with, Russia is probably the most corrupt, criminal and insidious. Its trade with South Africa is less than even small EU countries like Portugal, Belgium and the Netherlands. We need to be on guard against Russian oligarchs intervening in our electoral process, for example by becoming major funders of the governing party. Where this is the case, legislation is required.

South Africa’s trade with the EU dwarfs trade with Russia. South Africa exports goods worth R355-billion a year to the EU, but only about R6.9-billion to Russia. Total trade by all Nato countries with South Africa amounts to R1.38-trillion a year, compared with a mere R1.819-billion with Russia – around 1.3%.

The current governing party has strong party-to-party relations with governing parties in Africa as well as Russia and China, but there is scant evidence these are being used to advance South Africa’s interests in job creation, domestic growth, good governance or human rights.

Africa and southern Africa

South Africa’s foreign policy needs to take account of a fast-changing global order in which Africa’s role is becoming more important and fought over, the unipolar order has become multipolar, and long-standing global alliances are being recast. To take advantage of these exceptional opportunities while avoiding the dangers requires well-informed, dexterous policy-making and implementation.

Our foreign policy in Africa needs to harness all South Africa’s resources and expertise to grow its ties with the continent. These ties include its role as a gateway into Africa and to assist development where we have advantages we can offer, such as commercial, mining, industrial, university expertise and our constitutional structure.

The African continent is experiencing immense change. Progress is being made on aligning all 54 countries towards long-term low-tariff or tariff-free intra-African trade. The African Union’s importance is growing.

Some countries in the north of the continent are experiencing considerable population expansion which will make them among the most populous countries in the world, with increasingly attractive markets as well as heightened risks of instability.

New African oil and gas finds are changing power relations, while some are adopting smart economic innovations to build high-tech and green economic sectors (e.g. Kenya) and achieving world class growth rates (e.g. Rwanda, as well as Ethiopia until 2019 when civil war broke out).

In the last decade, South Africa has lost its place as the continent’s biggest economy, overtaken by both Nigeria and Egypt. Meanwhile South Africa’s economy stagnates at best – accelerating our already alarming unemployment and adding to the urgency to recover and grow our jobs market.

Southern Africa is a priority

South Africa’s fate and Africa’s are intertwined. This is even more true of our regional neighbours.

Our near neighbours in SADC should be a priority. Southern Africa has the potential to be a growing economic and diplomatic powerhouse, a market for our goods and services and two-way traffic of many kinds. This gives South Africa a strong interest in the wellbeing of all our regional neighbours.

Our recovery is significantly affected by the economic and political health of other southern African states. The decline of several neighbouring economies has ripple effects on South Africa.

Zimbabwe’s economic and political turbulence are of material concern for South Africa, which benefits from strong neighbours, and suffers when economic and political migration increase pressure at home.

Malawi’s subpar growth following Cyclone Freddy will take time to revive. Mozambique is burdened by armed conflict and corruption that has stolen the spoils of its massive gas find. A robust foreign policy should be actively seeking ways to help get these countries back on track.

As we set out to repair our policing and state-owned enterprises, make our economy more responsive to changing conditions and opportunities and strengthen our democracy, we have an interest in supporting our neighbours in these same areas.

Our aim should be to build this regional bloc, further integrating our economies. Building strong regional jobs and consumer markets, tourism and academic exchanges are a vital component of South African foreign policy. It is in our national interest for our neighbours to do well. It is the key to resolving many unsolved problems, including domestic xenophobia.

South Africa’s economy and ability to create jobs is harmed when a neighbouring country is weakened by economic collapse, and when loss of control of its currency inevitably undermines its sovereignty.

It is of material concern to South Africa, both as a good neighbour and for the wellbeing of our citizens, that Zimbabwe’s inflation, at 176%, is higher than war-torn Ukraine and Sudan, GDP growth is at 0.9% and nominal unemployment is at 20%, though unofficial estimates are much higher.

South Africa’s regional policies have underperformed for some time. It needs to use its relative strength sensitively, but also effectively. While taking care to avoid the heavy-handed American approach to smaller countries, South Africa should play a constructive role in getting neighbours back on their feet with financial and technical support, while encouraging constitutionalism and avoiding taking sides in their domestic politics.

South Africans have a right to expect a future in which southern Africa grows rapidly and sustainably, benefitting from the enormous potential wealth in Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo, as well as Zambia, Tanzania, Namibia, Botswana, Lesotho and eSwatini.

BRICS and the Global South

Critics who dismiss BRICS as a club we should leave are misguided. Reaffirming ties with the West must not mean damaging important relations with the rising powers of Asia and Latin America.

It is in South Africa’s interest to retain its valuable seat at the BRICS table, with its high-level access to rapidly rising powers China, India and Brazil. The Sandton Summit demonstrated its value. Its new members will open up new potential as well as risks.

The expansion of BRICS to include African, Middle Eastern and Latin American countries represents one step in a complex rearranging of global influence whose implications are in flux.

On the one hand, the US dollar will remain a vital part of global currency for many years, while countries of the Global South slowly begin flexing their muscles. The exact political, economic and diplomatic role of BRICS remains far from certain.

The benefits of South Africa’s membership go beyond direct loans, and include access to the governments and leaders of some of the most powerful countries in the world. We need these countries for their investments, for their technology transfers, for their markets. Many similar sized countries would give a lot for this opportunity.

What is missing is a clear and implemented South African agenda to benefit from these vast opportunities. South Africa must take ownership of its own needs – in short, have agency. What does South Africa need from China, India, Brazil and Russia? Are we getting what we most need, or are they defining these relationships? Russia and China have entered our mining industry. What does South Africa get in return? Political access? Bribes? Infrastructure designed by South Africa, or what they choose to provide?

No example of our unequal relationship with China is as stark as was demonstrated with the corrupt import of more than R100-billion worth of Chinese locomotives for Prasa and Transnet.

From the little that has emerged of the secret negotiations between our government and China, it appears that China remains deaf to our requests for spare parts for locomotives already purchased because of a SARS dispute and our ongoing investigation into the bribes that accompanied these deals, which were the biggest of the State Capture projects.

Our role in BRICS has lacked the nuance and sophistication that accounts for the vast differences between its members. Relations between China and India, for example, have been extremely tense, especially since the 2020 border incidents in which India claims dozens of its soldiers were killed. India has almost exclusively Russian military hardware, yet it is expanding its military contacts with the US.

India, Brazil and China have at times made clearer denunciations of Russia’s Ukraine invasion than South Africa. Each has adjusted its position as circumstances altered.

We are not obliged to agree with their positions or Russia’s. Instead we must be guided by South Africa’s particular interests, partnerships and values. There is no need to relinquish our commitment to constitutional democracy, human rights and the rule of law, while being acutely aware that we cannot impose our style of government on them.

Our BRICS partners choose their own foreign policy paths that often differ from each other. We must do no less.

The South African diaspora

We should learn from India’s conscious exploitation of the Indian diaspora to foster technology and capital transfers back to the homeland.

South Africa’s diaspora offers rich pickings for South Africa if we make South African expatriates’ expertise, capital, donations and engagement more welcome. Many millions of dollars in ex-South African US taxpayers’ tax-deductible donations and grants are spent in South Africa every year, but this could be enhanced and strategically targeted with more government diplomatic support.

The pro-west democracies

South Africa’s domestic prosperity and peace depend on a rapid job-creating economy to reduce our country’s scandalously high unemployment. We need partners for multiple purposes.

As a sovereign state, South Africa has the right and the obligation, to speak out when foreign governments’ actions threaten peace. This includes criticising western democracies which have conducted damaging military adventures during this century and participated in human rights violations of prisoners.

South Africa is southern Africa’s regional power, the continent’s most industrialised nation, a bastion of democratic constitutionalism, a free press and an independent judiciary.

Representing those values is a major feature of South Africa’s “soft power”, the reason why our diplomacy has at times punched above its weight. Abandoning those values signifies weakness, not strength.

Where the west has been tempted into military adventures aimed at “regime change”, we have objected, and should continue to do so. Attempts to change other countries’ governments violates the United Nations Charter as well as being unwise policy with dangerous and unforeseen consequences.

Our status as a values-driven country represented by leaders of international stature gave us a valuable seat at the table at G7 meetings, even when the size of our economy did not justify this deference. There are numerous benefits from this position. It gives us access to Western investment, loans, aid and markets. Western nations are the major consumers of South Africa’s value-added goods including motor vehicles, which are a key component of South Africa’s industrialisation and faster growth.

As the shape of the new multipolar world evolves, the US is likely to remain a major superpower and Europe one of the three most powerful blocs. The US, Europe, India, Japan, Australia and South Korea and others share and respect our values as a constitutional democracy, though India has been accused of violating the rights of journalists, for example.

Despite recent wobbles in these relationships, South Africa can still tap into enormous goodwill, as long as our differences are soundly based and defensible. We need to secure Western markets that have been put at risk since the Russian war in Ukraine.

The Ukraine war has demonstrated how warfare has changed since South Africa’s 1999 arms deal, and how advanced Western technology is compared even to Russia’s.

South Africa also needs partnerships for technological expertise, which can be accessed from advanced democracies including Japan, India and South Korea.

Advanced economies are willing to support efforts to develop renewable energy and cope with the consequences of climate change by building sea walls, improving drainage or developing early warning systems for floods and cyclones.

It is a time when well-planned proposals will likely be well received. This won’t be the case for long, and needs to be exploited while it’s there. South African soft power and international goodwill are valuable commodities.

Don’t waste them. DM

Next: Energy – South Africa’s once-in-a-century opportunity

Comments - Please login in order to comment.