SPOTLIGHT OP-ED

SA’s new mental health plan and the problem of stigma

Mental illnesses and the labels that go with these illnesses are often associated with stigma, which in turn influences health-seeking behaviour and adherence to treatment. Spotlight looks at how South Africa’s National Mental Health Policy Framework and Strategic Plan 2023-2030 addresses stigma and asked some experts for their views.

Before being diagnosed with bipolar disorder Type 1, Sifiso Mkhasibe says he did not know where to go for help. He was often dismissed as crazy.

“My immediate family did not know how to help or support me,” he says.

“I was always labelled the black sheep of my family. I was told that I was crazy, bewitched and that I was just pretending to be sick. I was told to be strong and to get over myself and that this disease is a white man’s illness and black people do not have such things.”

Mkhasibe says his family thought it was a cultural thing and that he had an ancestral calling to become a traditional healer. He did not agree.

The South African Federation of Mental Health (SAFMH) defines stigma as “an attribute, quality, or condition that severely restricts or diminishes a person’s sense of self, damaging their self-worth, social connections, and sense of belonging”.

The challenge of getting help

“It was extremely challenging to get help and support from my family. They played a big role in stigmatising me,” Mkhasibe tells Spotlight.

A delay in accessing mental healthcare services led to Mkhasibe’s condition deteriorating. He says some of his symptoms were racing thoughts, impulsive spending, hearing voices, and insomnia.

“I was always high on life with extreme energy levels. Things became worse, whereby I became violent and aggressive. I was eventually admitted to Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital in 2007 and later transferred to Sterkfontein Psychiatric Hospital in Krugersdorp.

“I was never informed about my diagnosis… what it was and how to manage it. I had no idea what to do when I was diagnosed. The challenge was that I was not educated about my mental illness,” he says.

Mkhasibe says he was in Sterkfontein Hospital until 2011. By then, he was estranged from his family and moved around a lot staying with cousins, aunts and his late grandmother.

“I was at Sterkfontein for four years. My family did not want me back home. I moved from one ward to the other during that time. Now I’m close to my sister and mother again, but it took a while to mend those bridges.”

He says his experience with the illness prompted him in 2011, after he was discharged from the hospital, to start volunteering and creating awareness of mental health conditions.

Sifiso Mkhasibe was diagnosed with bipolar disorder in 2007. (Photo: Supplied / Spotlight)

Mkhasibe is now 39 years old and was until recently a project leader for mental health at the SAFMH. He started at the organisation in 2017. On leaving, he says he has learnt a lot, but now has a newborn son and wants to spend time with him. Mkhasibe describes himself as a family man. He is married with two children.

Stigma and seeking care

Ashleigh Craig, a clinical psychologist who runs a Johannesburg-based private practice and has also worked in the public sector, says beliefs around mental health contribute to stigma because there are negative connotations surrounding mental illness.

“People seeking care are often called names such as bewitched or crazy. This prevents people from seeking out care,” says Craig.

“This results in people seeking care when their condition is acute and recovery will take much longer. Stigma can often lead to people completely stopping treatment.”

The South African Federation of Mental Health (SAFMH) defines stigma as ‘an attribute, quality, or condition that severely restricts or diminishes a person’s sense of self, damaging their self-worth, social connections, and sense of belonging’. (Photo: Spotlight)

Claire Hart, a postdoctoral fellow at Wits University’s Developmental Pathways for Health Research Unit, says the label of any mental illness is often also associated with a mark of social disgrace or stigma. This has been shown in South African communities, where studies revealed high levels of stigmatisation towards individuals with mental disorders.

The label of having a “mental illness” constitutes negative external perceptions which may, in turn, be internalised and negatively impact an individual’s internal sense of self.

“As a result, these individuals may avoid using existing mental healthcare services in fear of being labelled even when experiencing severe psychological distress. Thus, both having a mental illness and seeking help may be viewed as undesirable,” says Hart.

Under-funded, under-resourced

Hart says fighting stigma requires a two-fold approach that involves education and providing adequate resources.

“People with lived experience can help in terms of fighting mental health stigma and raising awareness. However, mental health is underfunded and there is a shortage of psychologists in the country. To become a registered psychologist you need a Master’s degree, and most universities only take six to 12 Master’s candidates per year,” says Hart.

Craig says people in the public sector can wait up to four months just to see a psychologist. She says private psychologists are very expensive and in the public sector most mental health services are only available at tertiary hospitals.

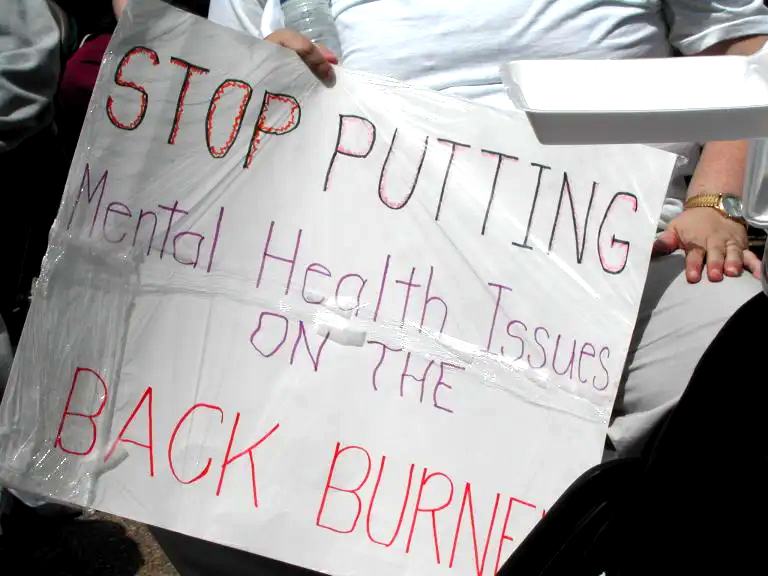

The mental health policy framework also sets out to strengthen mental health promotion, prevention and advocacy. (Photo: Liz Spikol / Flickr / Spotlight)

According to South Africa’s new National Mental Health Policy Framework and Strategic Plan 2023-2030 (the mental health framework), the country has less than one psychologist for every 100,000 people. This is among the reasons why there are limited mental health services in the public health sector, especially in rural areas.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Experts welcome new mental health policy but raise concerns over implementation

“At present, mental healthcare in rural areas, preventive and promotive aspects of mental health, and the provision of services to children, adolescents and those with anxiety, mood, and other non-psychotic disorders, remain under-resourced and underdeveloped. Furthermore, primary healthcare workers are under considerable strain due to high caseloads and have minimal training in mental health, resulting in patients receiving inadequate mental healthcare,” says Hart.

The social and economic costs

Data in the mental health framework indicates that about 5% of the total public health budget was allocated to public mental health expenditure in 2016/2017. Provincial public health budget allocations towards mental health showed marked inequality, ranging from 2.1% to 7.7% across provinces.

According to the mental health framework, social costs of mental illness can include disrupted families and social networks, stigma, discrimination, loss of future opportunities, marginalisation and decreased quality of life.

Mental illnesses such as depression and anxiety have been estimated to cost the economy more than R61.2-billion in lost earnings, according to the mental health framework. It states that at a societal level, lost income associated with mental illness far exceeds public sector expenditure on mental healthcare.

In other words, it costs South Africa more to not treat mental illness than to treat it.

What to do?

Although the mental health framework goes to great lengths to stress the impact of stigma on mental health, its plans to address this are relatively low in detail.

According to the framework, all health staff working in health settings will receive basic mental health training, inclusive of anti-stigma training, and ongoing routine supervision and mentoring. Provincial departments of health are meant to look at expanding their mental health workforce.

The framework also sets out to strengthen mental health promotion, prevention and advocacy.

“Currently, however, no concerted national programme exists,” the framework states.

“In 2024, a national public education programme for mental health will be established, including knowledge of mental health and illness; stigma and discrimination against people with lived experience of mental illness.”

This, according to the policy framework, will be steered by the national health department and provincial health departments. Other relevant government departments, including Employment and Labour, Education, and Social Development will, among others, introduce mental health literacy programmes into curriculums or workplace policies and decrease stigma.

But according to Michel’le Donnelly, a project leader for advocacy and awareness at the SAFMH, there is no clear outline for any anti-stigma programming in the mental health policy framework.

“As the SAFMH, we hold the view that the South African government needs to actively ensure that there is sufficient funding targeted for anti-stigma programming. Monitoring, evaluation and implementation of these programmes should be done in collaboration with people with lived experience of mental health conditions and NGOs working in the sector.

“These programmes should include contact-based education as part of governments intended activities because, through evidence and research, this has proven to be a way of ending stigma.”

Mkhasibe agrees that we need more support to make people aware of mental health services and how to fight stigma.

“We need more community engagement in terms of mental health education and awareness. People all over South Africa need to know that poor mental health is more prevalent than we think. Businesses and organisations need to instil mental health training as a culture in the office,” he says.

“Schools, colleges and universities should make mental health a priority within education. Awareness campaigns should be done at churches, malls, taxi ranks, airports and bus stations. Basically, everywhere where people gather,” he says. DM

This article was published by Spotlight – health journalism in the public interest.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.