MATTERS OF THE ART

Uche Okeke – of legacies, interactive artworks and minting NFTs

Creating a legacy is demanding enough. But sustaining it, keeping it fresh, tight and relevant in an ever-trending, dog-eats-dog art world is much harder. With this new initiative, Professor Uchefuna Christopher Okeke’s progeny are creating an evolving legacy for their father and the father of African Modernism.

“Young artists in a new nation, that is what we are! We must grow with the new Nigeria and work to satisfy her traditional love for art or perish with our colonial past” – Uche Okeke, Zaria Art Society Manifesto, Natural Synthesis (1960 Nigeria’s independence from Britain)

It was the father of African Modernism and a Nigerian national treasure, the late Professor Uchefuna Christopher Okeke’s deepest desire to leave a living legacy. Okeke was an artist, academic writer, illustrator, sculptor, prolific art collector and, most importantly, a “bridge builder”. No one quite knows how this idea took hold, but his daughter, Salma Uche-Okeke, suspects that it may have been planted through her father’s “ferocious reading”.

A living legacy is a bit of a contradiction with its old school, more-dead-than-alive connotations. But Okeke’s legacy was not an investment in self-importance or even about his art works or limited to the visual arts. Rather it was one seated in a deeply held, humanitarian philosophy of improving humanity through connection, expansion and open mindedness. In a true democratic approach, he “wanted his facilities and intellectual property to be made available to the world”. Salma explains that her father’s “direction not about producing art” so much as “it was about creating an enabling environment for artists in Nigeria and outside Nigeria”. He “developed a curriculum for them, helping to push Nigerians outside of these shores. He wanted it (art) to be a career path that anybody would be proud to be involved in, and be sustainable.”

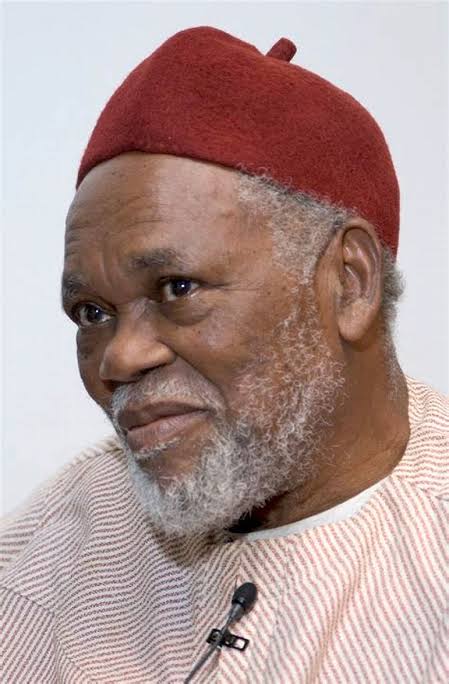

Uche Okeke (1933 – 2015). (Photo: Shelley Kusnetz)

Her father “wanted to project his ideas further, and he knew that the best way to go about it was to institutionalise his ideas. What he wanted to leave behind could not go as far if it was just embodied in his own personal achievements, so he needed to be bigger than that. He was already collecting other artists’ work; he had large archives, a library and people who donated from all over the world.”

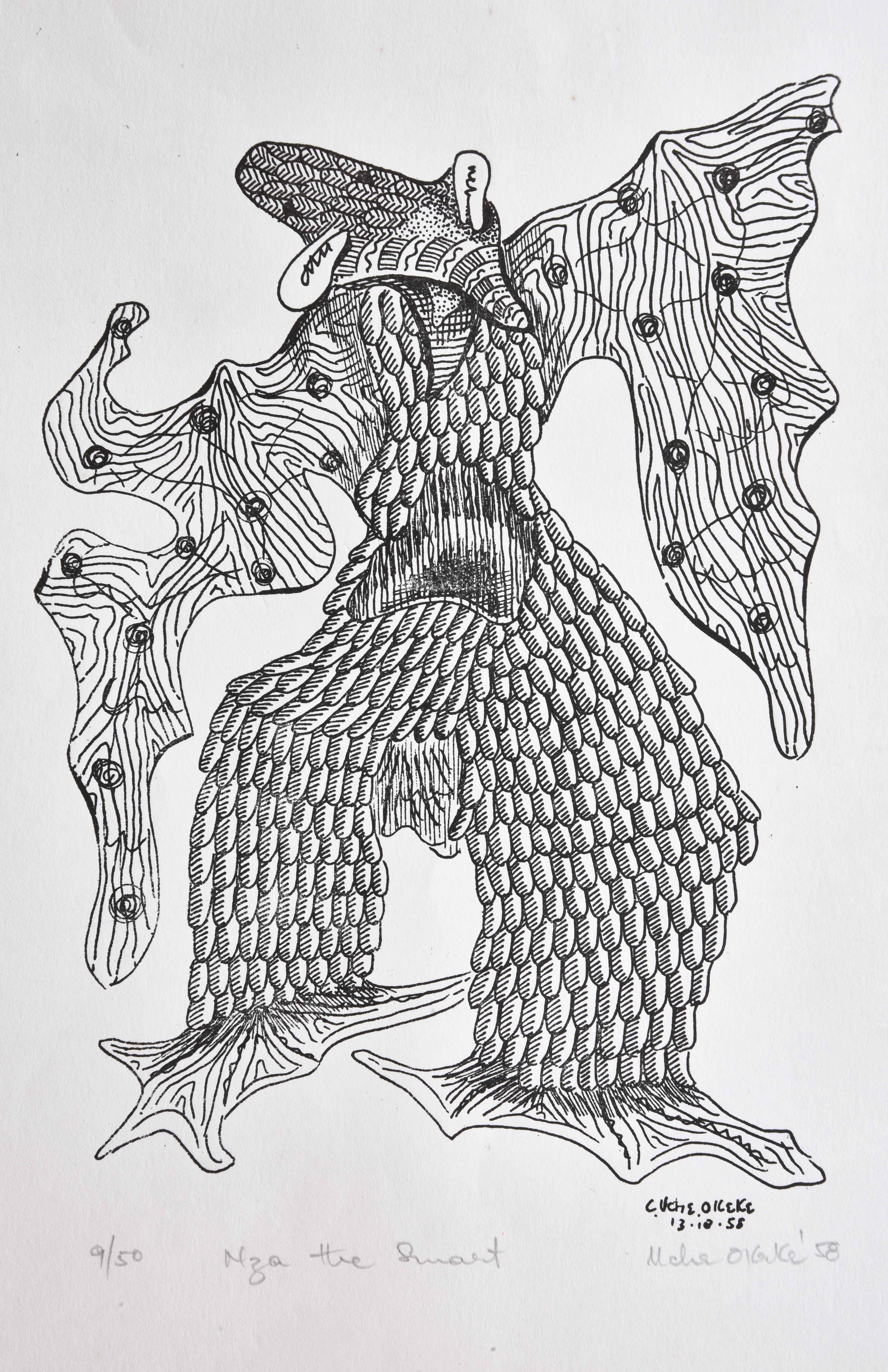

‘Nza The Smart’, Uche Okeke, 1958. (Image: Supplied)

In his 70th year Okeke started working with a young man who had sought him out and was helping him enter the digital world. Tragically the young man was murdered, and the process not completed. “My sister and I said: ‘Well, if this young man who has already started this process is not here we must continue’,” said Salma. So the sisters took the blueprint of their father’s living legacy and put a spin on it. In keeping with his progressive outlook the Okeke sisters introduced a digital idea that would mirror his game-changing, innovative approach. One which ticked all the boxes of originality, fun and engagement. And it’s globally accessible and inclusive and, more importantly, encourages participation. A dynamic legacy for “generations to come”.

Okeke’s legacy kicks off with a regular website highlighting a comprehensive and careful selection of works that best reflect his particular ethos and context. Then the fun begins. So often exhibition goers go to a show where they get to do eyeball work which maybe includes a feeling and or thinking response. Consumption is often limited to the cerebral. It’s definitely not a scratch-and-sniff experience. Any physical involvement is strictly off limits; no touching when so often works seem to beg to be felt. You may taste but only with your eyes. And no smelling, you must keep your distance. And definitely no interactive modifications whatsoever.

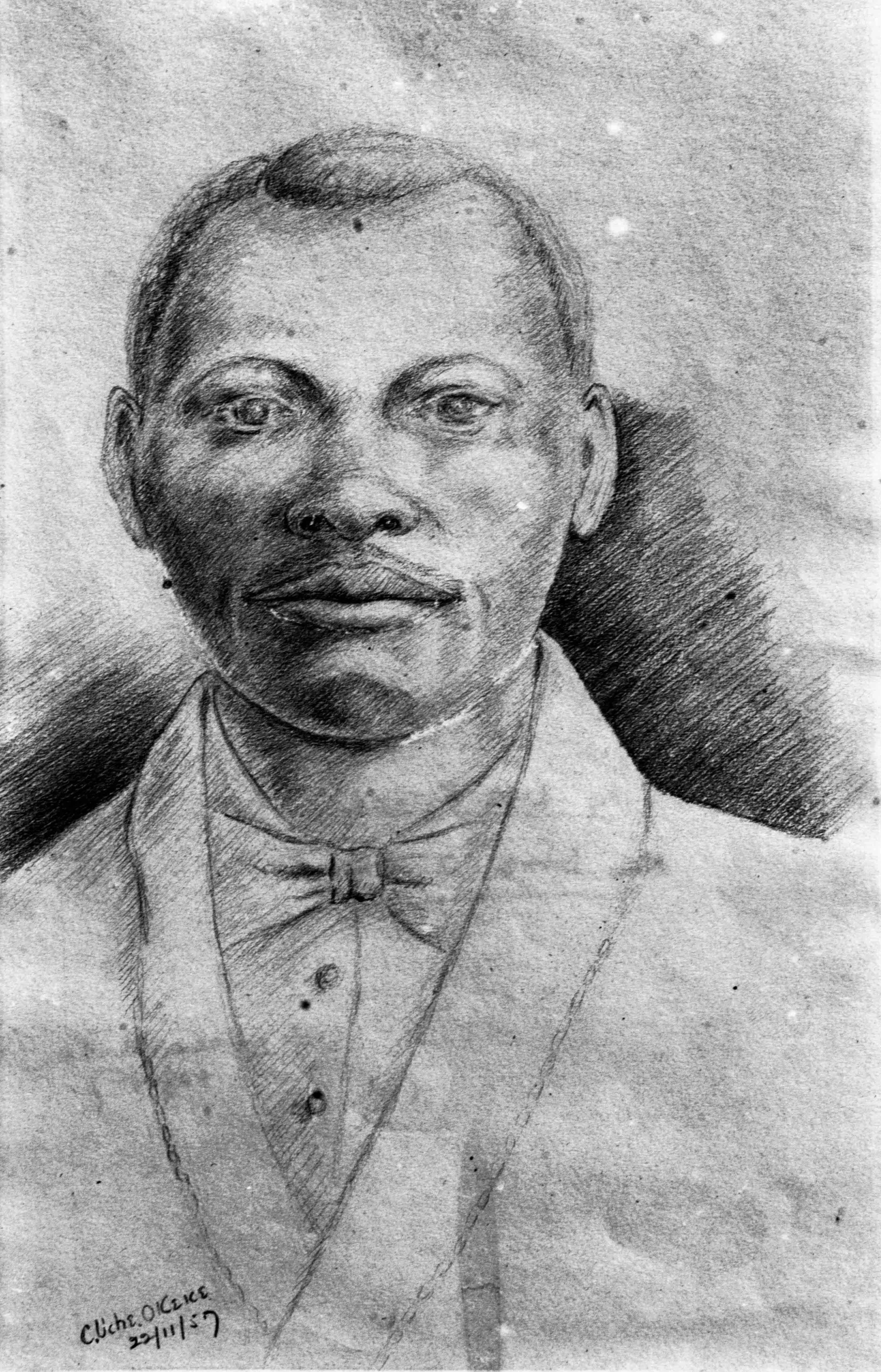

‘Portait of Mr Isaac O. Okeke’, Uche Okeke, 1957. (Image: Supplied)

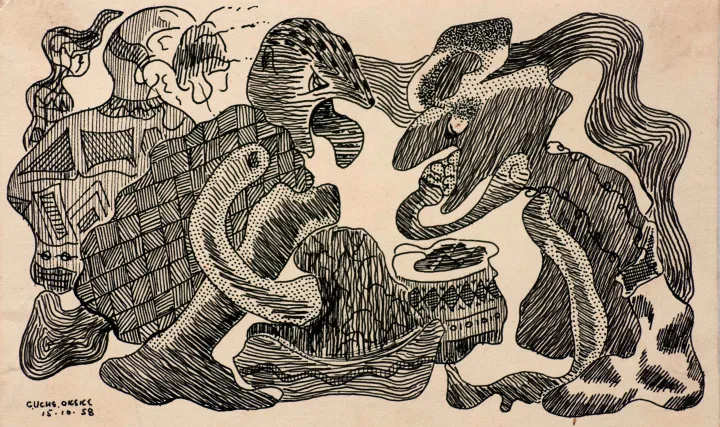

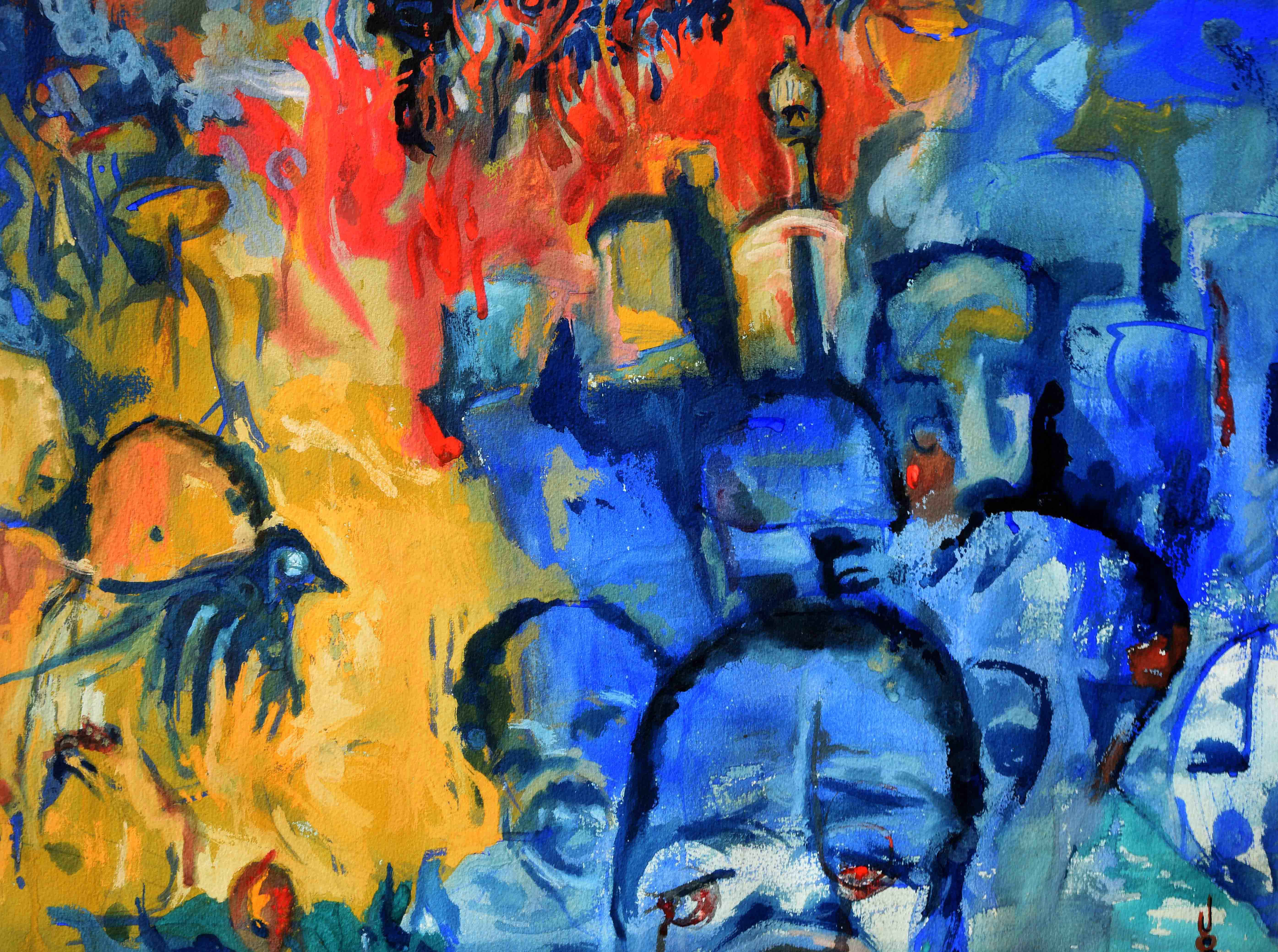

‘Bring With Oveearly Birds Nimo’, Uche Okeke, 1993. (Image: Supplied)

This is where the Okeke’s legacy ratchets up and shakes off the staid idea of legacy and the passive interaction with artworks. Via an app on the website, visitors to the site get to choose works to interact with. It could be Okeke’s drawings, brightly coloured paintings or monochromatic pieces in a variety of mediums – the range is wide. Once a work is chosen, visitors to the site can make changes using the app, thereby engaging with the creative spirit underlying Okeke’s primary creations, and at the same time add their own flavour. These modifications are then translated into unique, can’t-be-copied NFTs (non-fungible tokens or digital assets). These will then be assessed by art experts and the top NFT will be minted. This is a great opportunity for the chosen because with NFTs you don’t have to rely on a middleman (read gallery), you can sell your token directly to the consumer and get to keep the profits and you stand to get royalties every time your token is sold to a new owner. Plus, your token has been ratified by the Okeke legacy.

One gets a sense of Professor Okeke giving a bearded smile from under his signature beret.

So, who was Professor Uchefuna Christopher Okeke? For Nigerians, he was the father of African Modernism. He also reintroduced the traditional Igbor Uli style and was one of the founder members of the Natural Synthesis movement and the recipient of the MFR (Member of the Order of the Federal Republic) by the president of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, and the Federal Government Award for distinguished service in the arts and culture sector.

For South Africans, he was the artist who designed the late archbishop Tutu’s throne and portals in the Holy Trinity Cathedral in Onitsha, Nigeria.

Those of us who read Chinua Achebe’s best-known novel Things Fall Apart as a school or university set work may have seen the accompanying illustrations by Okeke. These illustrations use a flat-line style which shows the influence of the traditional Uli abstract style. The style has been interpreted as challenging the “colonial modes of literary representation and the myth of modernist primitivism in the visual arts”. Okeke also did the sets by another great Nigerian writer and Nobel Prize winner, Wole Soyinka, for the play The Lion and the Jewel.

South Africa’s connection with Nigeria begins with the obvious – the springbok and the eagle both share the African continent. We also both share a dark past as colonies under British rule. Our relationship with Nigeria intensified in the 1960s and 1970s when, in solidarity against apartheid, Nigeria implemented international economic sanctions, gave assistance to victims of apartheid, provided financial support to black South African students, issued Nigerian passports for exiles and opened up opportunities for study in Nigeria.

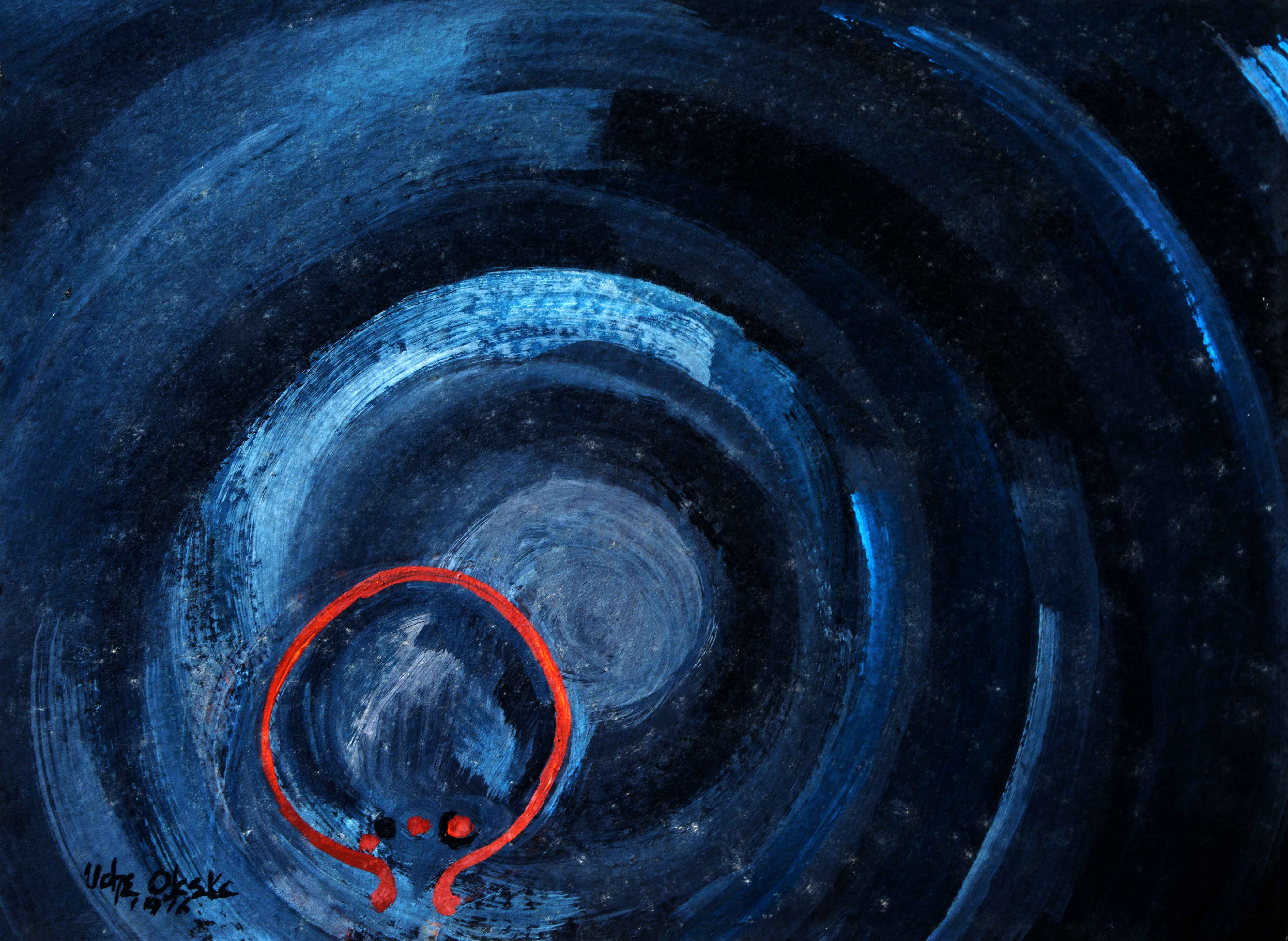

‘Gouache,’ Uche Okeke, 1976. (Image: Supplied)

‘Anyanwu Of Agbala Were Not There Only Coldness’, Uche Okeke, 1976. (Image: Supplied)

Salma explains that traditionally it was the responsibility of the eldest son to continue the cultural customs, leaving the youngest free. Like his father, Okeke was the youngest son. Their shared positions in the primary family meant that because neither of them were yoked to tradition and in particular they could leave their immediate locality and be open to influence by the diversity of people from other parts of Nigeria. The big names from Okeke’s generation “had big interests rather than (with) the immediate”. Salma explains “that there was a kind of renaissance going on all over the world at that time and the beginnings of globalisation were being felt”.

For those who knew him, Okeke was an approachable mentor to both young and old. A man who treated people equally. He could have been a doctor or a lawyer, as his mother wished. However, already in secondary school, he became involved in mural-making and was infected by the creative bug. Salma describes her father as a sponge. He was “constantly trying to learn more about the past and the present and trying to extrapolate it into the future”.

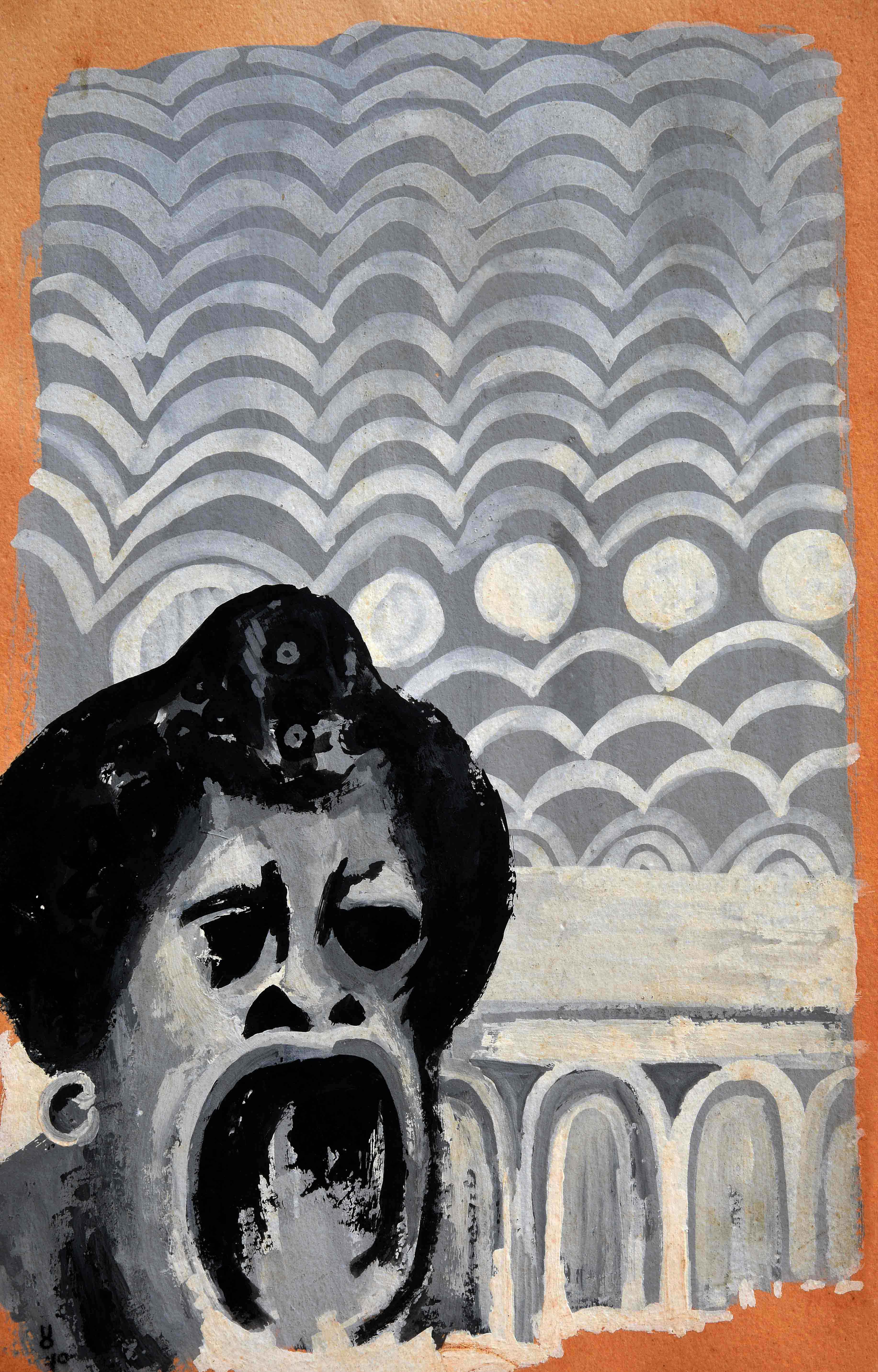

‘A Maiden’s Cry,’ Uche Okeke, 1970. (Image: Supplied)

For his daughters, growing up with him, they acknowledged that they maybe took things for granted. However, one thing they were sure of was their father’s uniqueness. “For us, he was the man who encouraged us to take our own life decisions knowing that we would be responsible for whatever decisions we took,” Salma said. There is seamlessness between the personal legacy his children inherited and the public legacy. “One of the most important things I learnt from him,” said Salma, “was to live a life of purpose, to make sure that your life counted, to make sure that there is something you are leaving behind. You may not be the beginner of the idea but you have helped to develop it further and added a little more value to humanity.”

Okeke was born in Nimo, southeast Nigeria. His life spanned three major events in Nigeria. He lived through 30 years of British colonisation, Nigeria’s liberation in 1960 and the post-independence three-year civil war between the government of Nigeria and the antagonist state of Biafra.

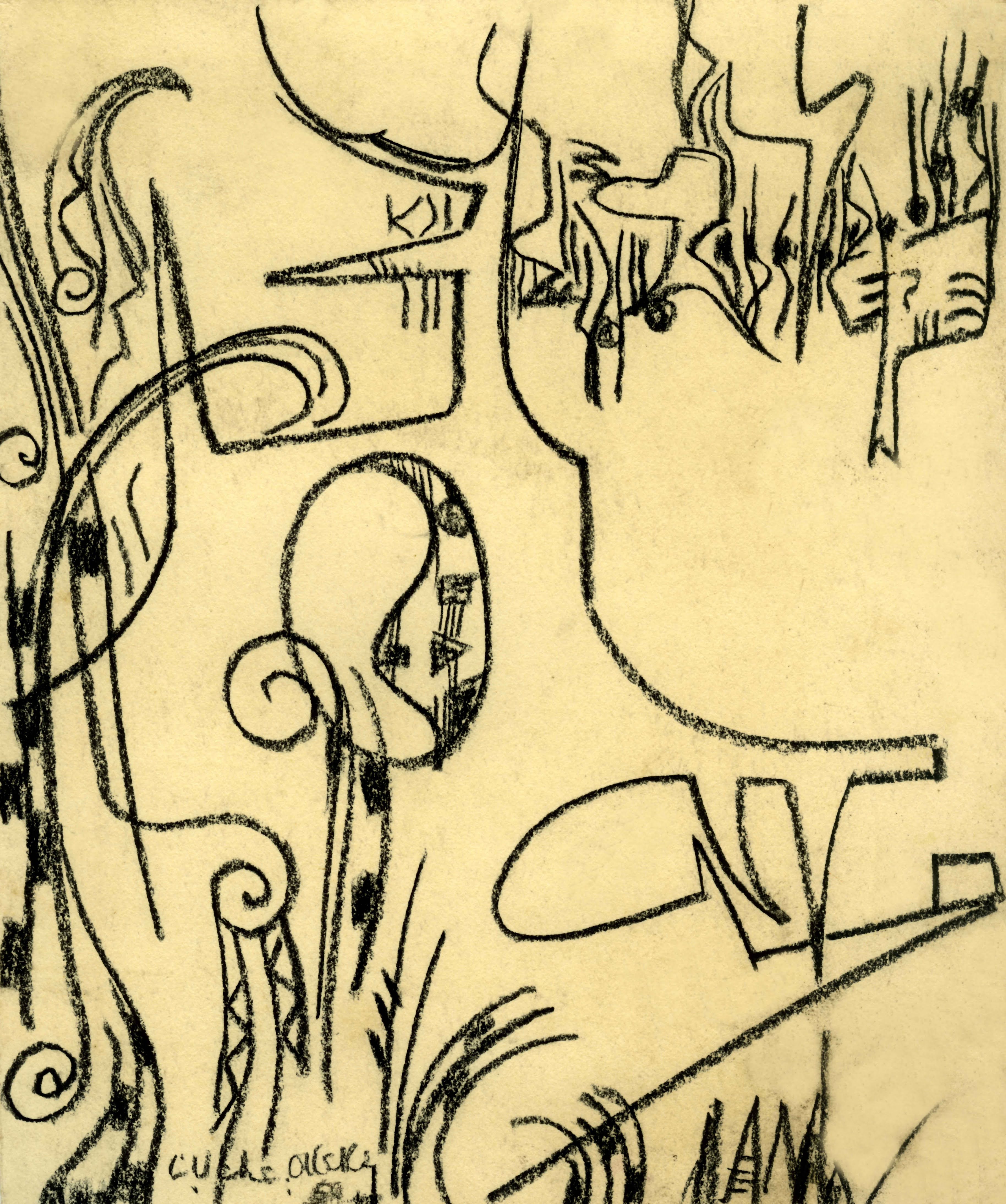

A decade before Nigerian independence, Okeke and four other artists and art students from the technikon developed an approach called Natural Synthesis. It was a merging or hybrid of Western and Nigerian traditions and cultures including Yoruba Igbo, Urhobo as well as bible stories, local histories and indigenous traditions, to create a modernist vocabulary informing a post-independence identity. This was seen as a rebellion against the focus of Westernised teaching of art in academia and a way of restoring dignity to colonised people.

‘Beast Savanah Country,’ Uche Okeke, 1959. (Image: Supplied)

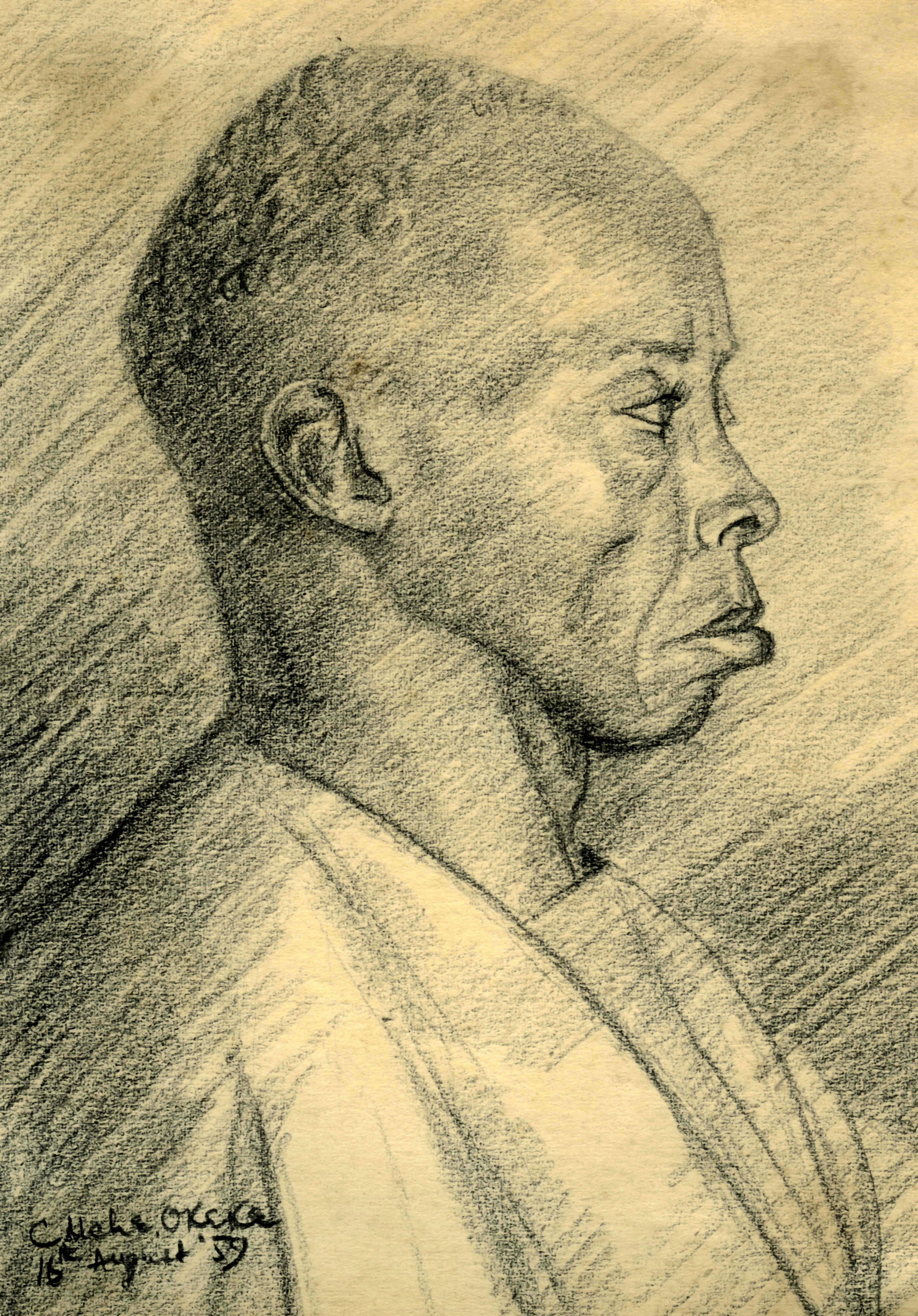

Uche Okeke, 16 August 1959. (Image: Supplied)

Artwork, Uche Okeke. (Image: Supplied by the author)

According to the late Ola Oloidi, professor of fine arts at the University of Nigeria Nsukka, Okeke’s most creative achievement was the modernisation of the traditional Igbo Uli art. Uli art has been described as “a line going towards a void”. Okeke learnt its form from his Igbo mother who was also a midwife and traditional healer. Salma explains that the style was used to decorate bodies and traditional mud houses. The lines themselves could carry messages and are a language that includes both the aesthetic and the spiritual. The endless researcher and intellectual that he was, right up until his stroke Okeke was still investigating traditional and cultural forms.

For the first time, Salma and team are in the process of having a conversation with South Africa regarding her father’s legacy and are really interested to see what we think of it and how it resonates with them. DM

Okeke’s living legacy launches on 27 August 2023.

Visit ucheokekelegacy.com and engage with this mover-shaker, be influenced and then find your own interpretation and respond interactively.

Comments - Please login in order to comment.