SPOTLIGHT IN-DEPTH

How big a problem is TB in South Africa’s schools?

While there is limited data on tuberculosis in South Africa’s schools, a growing body of evidence suggests there is significant TB transmission in our often overcrowded classrooms. Tiyese Jeranji spoke to local experts about what we do and do not know about how this age-old disease is affecting pupils and their households.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 304,000 people in South Africa fell ill with tuberculosis (TB) in 2021. Since only a fraction of people who breathe in TB bacteria will fall ill, the number of those who would have been exposed to the bug in 2021 would be much higher. Many of these people exposed to, or ill with TB would have been children or teenagers.

Since TB is transmitted through the air, transmission is thought to be particularly high in enclosed and overcrowded places, such as South Africa’s notoriously overflowing classrooms.

The term scientists are increasingly using in this area is “shared air”. Dr Graeme Hoddinott, social science lead at the Desmond Tutu TB Centre and the Department of Paediatrics and Child Health at Stellenbosch University, says this simply means the air that is breathed out by one person is breathed in again by another.

“The more time we spend inside ‘boxes’ (for example, a room with closed windows or doors or no ventilation system), then the more times I will breathe in air that you have breathed out and vice versa,” says Hoddinott. He says the basic driver of TB transmission at school is people (pupils and their teachers) spending long periods in a space where bugs have time to accumulate, such as in a classroom with the windows and doors closed.

Hoddinott says that if some of this shared air has bugs in it, then odds are they will be breathed in. He references a campaign run by advocacy group TB Proof that argued: “We do not share water that looks like it has bugs in it, so why should we share air with bugs in it?”

Measuring the TB in the air

The idea that there is TB circulating in the air in classrooms in high-TB burden communities in South Africa is not only based on high TB rates and overcrowding in schools, but has increasingly been backed up by more direct research.

In one recent study, Dr Erick Bunyasi and colleagues from the South African Tuberculosis Vaccine Initiative (SATVI) measured both carbon dioxide (CO2) levels and TB particles in the air in 72 classrooms in two high schools. There were more than 2,200 pupils in the 72 classes they monitored. Similar measurements were also taken at three outpatient TB clinics to provide a benchmark. CO2 levels are a good measure of shared air, since they are higher in the air people breathe out than in the air they breathe in.

The study’s findings were not reassuring.

“More than one-third of 72 high school classrooms were inadequately ventilated, and one-fifth of classrooms had evidence of airborne TB DNA detected,” says Dr Angelique Luabeya, chief research officer at SATVI and a co-author of the study.

A learner with TB might spend a number of days in their classroom breathing or coughing when they should have been diagnosed and started on TB treatment

She also stresses the finding that the average risk of inhaling one TB DNA copy was similar between clinics and classrooms. “This was concerning because TB patients are more likely to attend the clinics. The fact that the clinic and the school have identical risks of exposure to TB DNA might suggests that there are undiagnosed cases among adolescents in classrooms who are exhaling TB bacilli at a comparable level to TB patients in the clinics,” she says.

Luabeya is clear about the implications of such findings. In communities with high TB prevalence, she says, schools become potential sites of transmission.

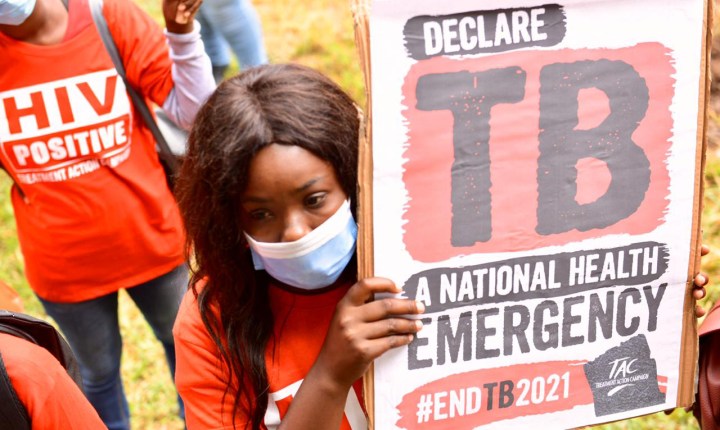

Late diagnosis of TB in adolescents and children increases the risk of further transmission in classrooms. (Photo: Jessica Wiggs / TB Alliance)

What it means for pupils

While the study by Bunyasi and colleagues identified only one case of active TB disease – which is likely to be an undercount since there was very little actual TB testing in the study – it leaves little doubt that there were TB particles in the air in several classrooms and that many children would have inhaled TB bacteria while at school. Some of them may have TB infection but not be ill with TB disease.

Dr Juli Switala, senior technical specialist for paediatric TB at the Aurum Institute, says individuals with TB infection don’t feel sick, since the TB is alive but not multiplying or doing any damage, and they are also unlikely to be releasing TB bacteria into the air. “This stable situation can go on for many years. The problem is that at some point later – it could be within weeks or years – the immune system may lose its control, allowing the TB bacteria an opportunity to multiply and start causing damage to the lungs and spread to other parts of the lung. This is what we call TB disease – and if it manages to reach the bloodstream, it can spread to any part of the body, including, worst of all, the brain,” says Switala.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Can taking two pills a week slow down TB in South Africa? There’s a new plan in place

“Even people with TB disease often don’t feel very sick at all, or take many months to notice that they are not well. Some may seek medical attention but because early TB disease is so mild and difficult to pick up, and [there is] no completely accurate test for TB, they are sometimes misdiagnosed,” she says.

Late diagnosis is not only harmful to the health of individual pupils who have TB disease, but it also increases the risk of further transmission. “A compounding factor,” Hoddinott explains, “is that adolescents with TB are far too often not diagnosed, or even if diagnosed, they receive care that is suboptimal. What this means is that a learner with TB might spend a number of days in their classroom breathing or coughing when they should have been diagnosed and started on TB treatment, which would rapidly reduce the number of bugs they would breathe out and thereby dramatically reduce the risk of transmission.”

A further complication is that pupils diagnosed with TB may face various forms of stigma. Hoddinott says it is important to help those who develop TB disease to have as little disruption as possible to their schooling. This includes letting them return to class as soon as it is safe to do so, accommodating them around exam periods, helping them to disclose or explain their absence to their friends or peers in a way that is safe, and ensuring that there is no lingering sense that the child might still transmit TB.

“Many adolescents affected by TB also experience huge mental health comorbidity (depression and anxiety),” he says. “And often, adolescents who develop TB disease come from contexts of hunger, poverty, etc. So, the headline is much more about showing care or love or respect for learners affected by TB and finding ways to mitigate the impact of TB on them, and not about TB transmission in schools.”

What to do about transmission in schools?

The most obvious solutions to the TB transmission problem are to reduce overcrowding and increase ventilation. While overcrowding in schools may not have any quick fixes, ventilation can be improved by opening windows and leaving doors open if feasible. New classrooms can be built with ventilation in mind. Having CO2 monitors in classrooms might also help in increasing teacher and pupil awareness of shared air and related risks.

According to Hoddinott, reducing transmission in schools (as well as homes, clinics, taxis, workplaces and churches) boils down to three things: “Appropriate infection prevention control measures (for example ensuring good airflow by keeping windows open, wearing masks if appropriate), getting people who have TB diagnosed quickly and offered treatment to reduce the time they are infectious (and get them better outcomes), and where appropriate, offering preventive therapy to people who are exposed to TB bugs (for example, the children living in a home of an adult who has TB disease).”

He adds that the headline message around TB in schools should not be about transmission, but rather about how to equip pupils, their teachers and parents with the knowledge and ability to access TB care early. This includes a need for much greater collaboration between the departments of Health and Basic Education.

Read more in Daily Maverick: We need more dedicated investment to address TB in children

Luabeya also warns against a too-narrow focus on transmission in schools. “To improve the situation, it is essential to have interventions that decrease the TB prevalence in the communities where the children live [contact tracing of TB cases and active TB case-finding activities].”

While regular TB symptom screening at schools is essential, she also points out that it will not detect subclinical TB – disease that has progressed beyond infection but not yet resulted in TB symptoms.

Government plans

The government department with primary responsibility for schools is Basic Education, to which Spotlight sent several questions about its plans to address TB transmission in schools, but had received no response by the time of publication.

However, according to the department’s annual performance plan 2023/24, it has allocated funds through the HIV and Aids Life Skills Education Conditional Grant to support the implementation of its national policy on HIV, STIs and TB for pupils, teachers and support staff in schools through health promotion programmes, including the HIV and AIDS Life Skills, Integrated School Health Programme (ISHP), HIV and TB, Comprehensive Sex Education, and Learner Pregnancy programmes. For the 2023/24 financial year the department allocated R241-million to this.

One of the topics discussed at the 7th SA TB Conference in 2022 was the need to strengthen the integrated health programme for schools. (Photo: Tiyese Jeranji / Spotlight)

According to the plan, the allocation will be used to train teachers to implement comprehensive sexuality education and TB prevention programmes for pupils to be able to protect themselves from HIV and TB. The department says it will prioritise schools in areas with a high burden of HIV and TB infections. The grant is also used to capacitate governing and other school bodies to develop policy implementation plans, focusing on keeping mainly young girls in school, ensuring that comprehensive sexuality education and TB education is implemented for all pupils in schools and that there is access to comprehensive sexual and reproductive health and TB services as well as implementation of TB services at secondary schools, the report states.

Among the outputs are to reach at least 45 districts “with the dissemination of the National Strategic Plan on HIV, TB and STIs 2023 – 2028 and the revised DBE national policy on HIV, STIs and TB”. At least 5,600 schools are set to be reached through monitoring and support visits. The report doesn’t contain much detail on how TB transmission will be mitigated in schools.

Yet, speaking at the South African TB Conference in 2022, during the Department of Basic Education’s satellite session themed “Prioritising Tuberculosis Response Among School-going Adolescents”, Deputy Basic Education Minister Dr Reginah Mhaule stressed the importance of building momentum in strengthening the integrated health programme for schools and adolescent-friendly healthcare.

“The Department of Basic Education will be ensuring that classes are not overcrowded, and that there is proper ventilation,” Mhaule said. “Part of what the department aims to do to control TB in schools is that screening is done at enrolment. We aim to raise TB knowledge in our schools and have a curriculum with more TB content.” DM

This article was produced by Spotlight – in-depth, public interest health journalism.

Comments - Please login in order to comment.