STATE CAPACITY OP-ED

Only a focused return to statecraft can arrest the degeneration of SA’s democracy

Building state capacity is about going back to basics — the nuts and bolts of making state institutions function for the good of society. Of critical importance is to ensure that we have in the employ of the state only those who are qualified and have an ethical disposition.

The National Development Plan (NDP) is the country’s lodestar for socio-economic transformation. It promises to eliminate poverty and reduce inequality by 2030, with economic growth and transformation, including job creation, being emphasised as key imperatives to realise these.

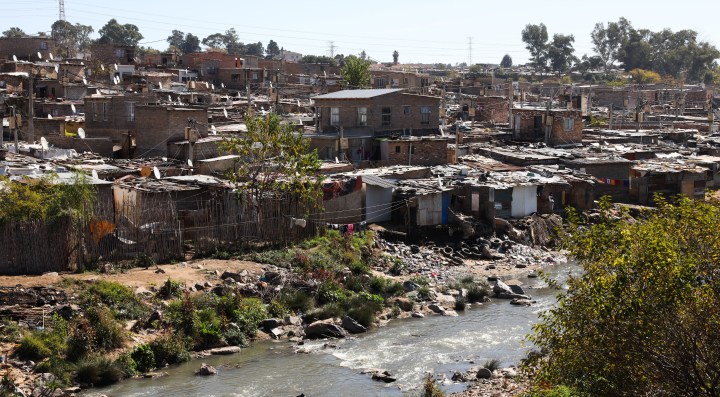

Its deadlines fall in less than seven years, but poverty and unemployment continue to rage unabated. The country is unable to shake off the label of being the most unequal society in the world.

As Statista 2023 shows, as of 2022, about 18,2 million people in South Africa languish in extreme poverty. This is, according to Statistics South Africa’s 2022 report, despite government spending that in the 2020/21 financial year had already surpassed the R2-trillion mark, with social protection, health, and general services accounting for the highest share.

More worrying is that there are 123,000 people who have been added to the penury stratum in 2022, compared to the previous year. The irony in this is that the ideas on how to change the situation have always been contained in the NDP, including that its implementation depends on strong state capacity.

The commitment to build a capable and developmental state in a constitutional democracy subsequently became a top priority in the Medium-Term Strategic Framework (2019-2024). This was a response to a call the NDP had made for “a state that is capable of playing a developmental and transformative role”.

But with all this, where did things go wrong?

The answer to this question lies in the lack of a sense of urgency to act on the NDP, which was embraced by all political parties in Parliament in 2012 as a grand strategy to change the country’s course. The NDP created an opportunity to galvanise the entirety of society around a common vision.

However, the initiatives to write its recommendations on building state capacity into law only began earnestly in 2021. This is 10 years since its adoption, and the focus of these initiatives has largely been on the structural aspects of institution-building, not on statecraft. This is where efforts to build state capacity fall short.

In the simplest way, state capacity is about how to “get things done” and this not only entails institution formation, but an institutionalising sleight-of-hand in public affairs. Dexterity in optimising the efficiency and effectiveness of the state is what matters now, not the grand ideas, strategy, or plans. South Africa has many of these.

Prof Eliot Cohen of Johns Hopkins University explains statecraft as a “sensing, adjusting, exploiting, and doing rather than planning and theorising”. He uses the analogy of the “skill of a judo player who may have plans but whose most important characteristic is agility”. South Africa needs this for things to get done in the provision of the public good.

Setting up institutions is not the same as having them work for the good of society. Systems and processes of governance exist to shape institutional disposition, but the public value of their existence is not always forthcoming.

And the danger inherent in this is that shorn of institutional capability building, state capacity tends to spawn institutional fundamentalism.

By institutional fundamentalism, we mean institutional arrangements built on systems and processes for the pretence that the public good underpins their existential essence, while in truth they are meant to deceive the citizenry and secure legitimacy through the optics of state power.

Iain McLean, the University of Oxford emeritus professor of politics, edifies the notion of the public good as a key variable in theorising state capacity. He says public good is “any good that, if supplied to anybody, is necessarily supplied to everybody, and from whose benefits it is impossible or impracticable to exclude anybody”.

In the public good, there is public value. And this obtains by strengthening “the causal relationship between the policies that governments adopt and the outcome they intend to achieve”.

Anything short of this presupposes an inefficient state. And such necessarily emerges when the strength of the causality between policy and its intended outcome is weakened. As the Report of the Commission of Inquiry into Allegations of State Capture — the Zondo Report — shows, this often happens for the self-serving ends of the political elite where their ambitions trump the public good.

In this, South Africa has joined many countries, especially in the Global South, where democratic politics is captured by weakening state capacity for patronage networks to hold sway. This damns the poor but serves the elite.

Leaving with their food parcels during a pre-Mandela Day Celebration by TZU-CHI Foundation and China Town, Ottery at China Town, Ottery on 16 July, 2022 in Cape, South Africa.(Photo: Gallo Images/Brenton Geach)

In their theory of emergence and persistence of ineffective states, Daron Acemoglu, Davide Ticchi and Andrea Vindigni say “societies with limited state capacity tend to invest relatively little in public goods and do not adopt policies that redistribute resources to the poor”.

Some may argue that this does not apply entirely to South Africa as social spending has been increasing exponentially over the years. The contention is that social spending represents distribution of fairness. But this holds only if state largesse takes the poor out of poverty. Unfortunately, in South Africa social spending simply keeps the poor afloat.

Poverty, unemployment, and inequality have surged alarmingly despite the increase in social spending. And this has not always been with concomitant increased revenue collection, along with which there is rampant corruption. It puts the spanner in the works of efforts to fix the state.

All these contradictions conspire to fudge social equity as a constitutional value and a democratic pursuit for a just society. The disconnect between government and citizens forms this way. It spawns public distrust.

Round Eight of the Afrobarometer Survey of 2019/2021 shows that trust in public institutions has plummeted to its lowest since first being measured in 2006; and this not only relates to the executive arm of government, but to the legislative, judiciary and constitutional oversight bodies such as the Public Protector. This does not bode well for the country’s constitutional democracy. It delegitimises the very system of government. A weak state capacity endangers democracy.

Gift of the Givers donate food hampers, blankets, Covid-19 and baby care packs to a group of about 115 extremely poor families at Mesco Farm on 7 July, 2021 in Stellenbosch, South Africa. (Photo by Gallo Images/Brenton Geach)

What is to be done?

Only a return to statecraft can arrest the degeneration of the country’s democracy. The approach to build state capacity needs to institutionalise capability in the country’s public administration.

This is about going back to basics – the nuts and bolts of making state institutions function for the good of society. Of critical importance is to ensure that we have in the employ of the state only those who are qualified and have an ethical disposition, and know what they are doing, including being fully conscious of the importance of performing their public function conscientiously.

Along with this is agility as the operational imperative to give effect to the state’s grand policy choices. We should not beat about the bush when coming to merit-based staffing practices. This is because state officials are not atomised frills but shape institutional culture. Their disposition needs to be built around the commitment to the public good.

In other words, who the state employs matters in institutionalising statecraft. The framework for the professionalisation of the public sector as approved by Cabinet in 2022 emphasises this. It gives strategic leverage for the evolution of meritocracy in the state’s recruitment practices.

Institutional capability building to enhance state capacity is a function of statecraft while a highly skilled and professional bureaucracy is a critical imperative of this.

Like any part of the economy, the public sector depends heavily on formal and educational training systems for its skills supply. However, research on the skills for the future of work in the public sector that we did for the Public Service Sector Education and Training Authority (PSETA) shows that the graduates of the post-school system have the qualifications, but not the skills to put knowledge to work.

Because of this, many a time the complaint is that their knowledge is not up to scratch. However, often this tends to be overgeneralised to obscure the complicity of recruitment practices within the state in instances of a skills mismatch. Their filters lack the rigour to ensure that recruits in the public sector are always placed in the position they are qualified for through education and training systems, which should eliminate the “misalignment between formal qualifications of public servants and the work they do”.

In addition to this being corrected, education and training for the public sector must be re-imagined along the philosophy that government is not a business but a democracy, and therefore must be run as such. The pedagogy of public affairs must be geared towards statecraft. This is what the urgency of the epoch for the reinvention of state capacity demands.

As the English economist Alfred Marshall put it, “the state is the most precious of human possessions, and no care can be too great to be spent on enabling it to do its work in the best way.” DM

Mashupye H Maserumule is Executive Dean of the Faculty of Humanities and professor of public affairs at the Tshwane University of Technology.

Ricky M Mukonza is associate professor in the Department of Public Management at the Tshwane University of Technology.

This article is based on research conducted on the skills for the future of work for the Public Service Sector Education and Training Authority (PSETA). They write in their personal capacity and views expressed in the article are theirs, not that of PSETA or the university.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.