WORDS ON THE STREET

Joburg’s inner-city bookshops subvert stereotypes of African illiteracy

The CBD’s ‘literary district’ is a haven for readers as business booms for booksellers, proving that South Africa’s abysmal literacy rates are a reflection of poor access rather than a lack of interest.

Stepping into Felix Nwigwe’s clothing boutique in Johannesburg’s central business district, you’ll be greeted by racks of wool coats, purses and books. With prices ranging from R50 to R100, the books cover more than 100 topics, from science and politics to religion.

Nwigwe migrated from Nigeria to South Africa in 2000. And, over 20 years, he’s built up a loyal client base. He also works as a pastor, and his bestsellers are spiritual and self-help books.

“I enjoy serving, helping people,” Nwigwe says. “As long as people are happy, I’m happy.”

Nwigwe is one of hundreds of informal booksellers in the CBD that make up the “literary district”, or a sprawl of book markets and vendors near Park Station and the Rand Club downtown. You can find vendors selling books on street corners, from their cars or backpacks, or within other stores such as hair salons or clothing shops.

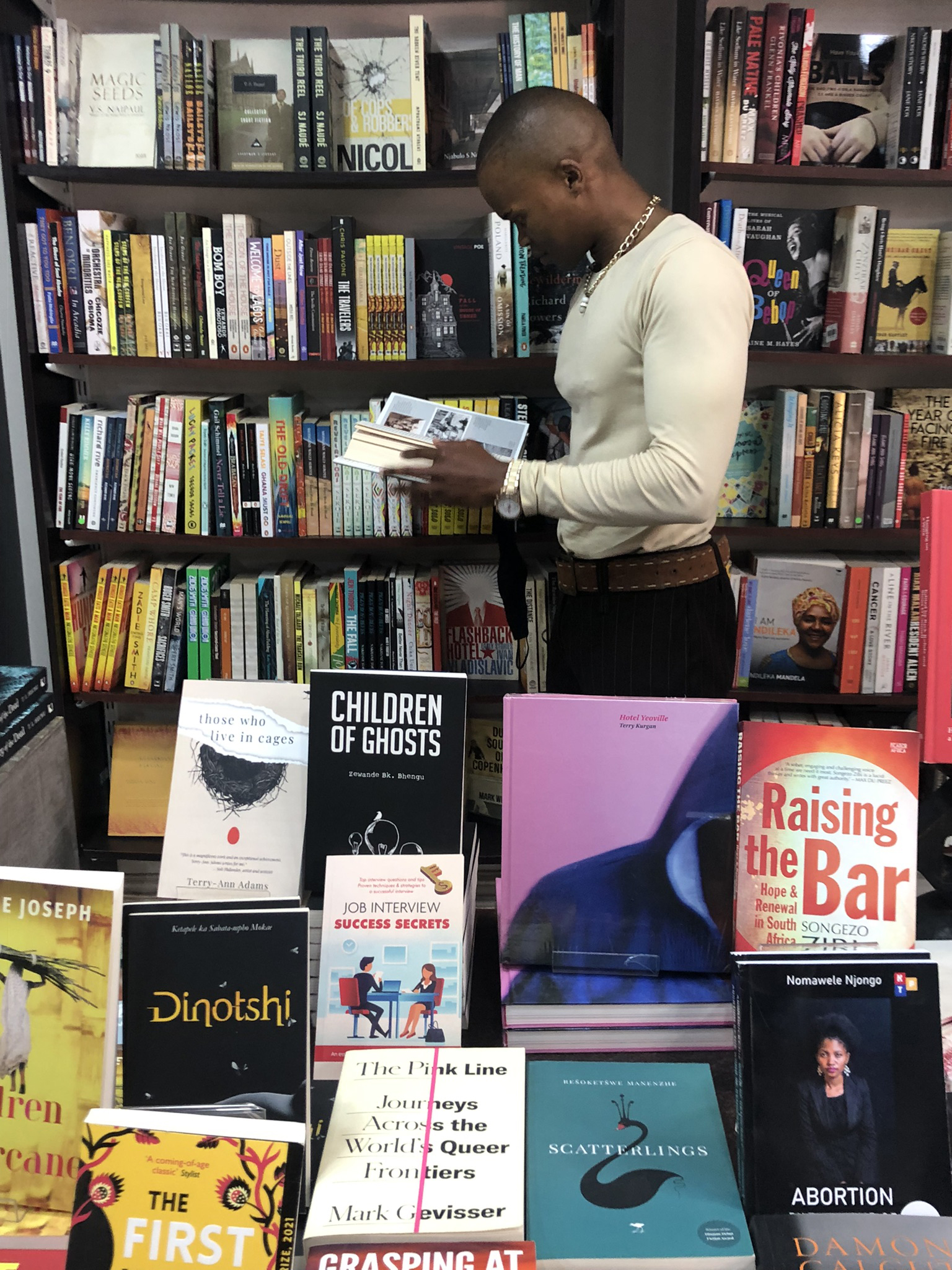

A man browses at one of the inner-city’s many bookshops supported by Bridge books, which works to amplify African authors and stories. (Photo: Bridge books)

Bridge Books, an independent bookstore in the area, has worked to gain recognition for Johannesburg’s literary district and uplift the informal booksellers that reach the city’s masses. It works to help African authors, create a more vibrant reading culture to subvert stereotypes of African illiteracy and share the joys of reading so it is accessible to all.

Its efforts are sponsored by a six-month grant, up for renewal this month, from the microfinance charity Small Enterprise Foundation.

No access to books

South Africa boasts concerning childhood literacy rates, according to a 2023 Pirls study. Instead of pointing the finger at young pupils, the statistics may instead reveal a lack of access to books for poor black readers that has hampered the country’s reading culture.

“How can you read something you do not have access to?” asks Zandisiwe Mhlekwa, who works with Bridge Books to coordinate outreach to informal booksellers. “How can you possibly say South Africans are not reading or not buying books when the books are not available for them to read?”

Books in South Africa are predominantly published in English and Afrikaans, which can seal off the reading culture for people with different home languages.

Johannesburg’s libraries are poorly maintained, book prices are high, and formal bookstores can be very isolating spaces for the country’s majority black population, Mhlekwa says.

Francesca Martis, the store manager at Bridge Books, says growing up she couldn’t find any books in the language she spoke at home. Having books in your own language affects how you grow up and how you see the world, she says.

“Beyond just allowing people the experience to read in their language, it also affects learning processes,” Martis says. “People learn better when they can learn in their own language.”

Martis says she read a lot as a child. Her mother would buy books from informal booksellers. As she grew up, she says she chose to read more African literature and African historical fiction written by women, because that’s what she grew up without.

Right now it looks as if black people do not read at all. And that is not true. We just don’t have the resources.

Still, African literature and books in African languages are hard to find affordably, Martis says.

The lack of data in the informal book market makes it seem like people aren’t reading, Mhlekwa says. But it doesn’t take into account the different avenues that people use to access books.

Read more in Daily Maverick: When art imitates life — lessons from Yizo Yizo for South Africa’s literacy crisis

Mhlekwa says formal bookstores, such as Exclusive Books, are often found in suburban malls, which cater to a whiter and wealthier audience. Many black people may not feel comfortable entering book stores because they do not think they are spaces for them.

“[Formal bookstores] are quite elite, quite exclusionary and not necessarily catered towards black people or poorer black people,” Mhlekwa says. She herself doesn’t always feel comfortable walking into a bookshop.

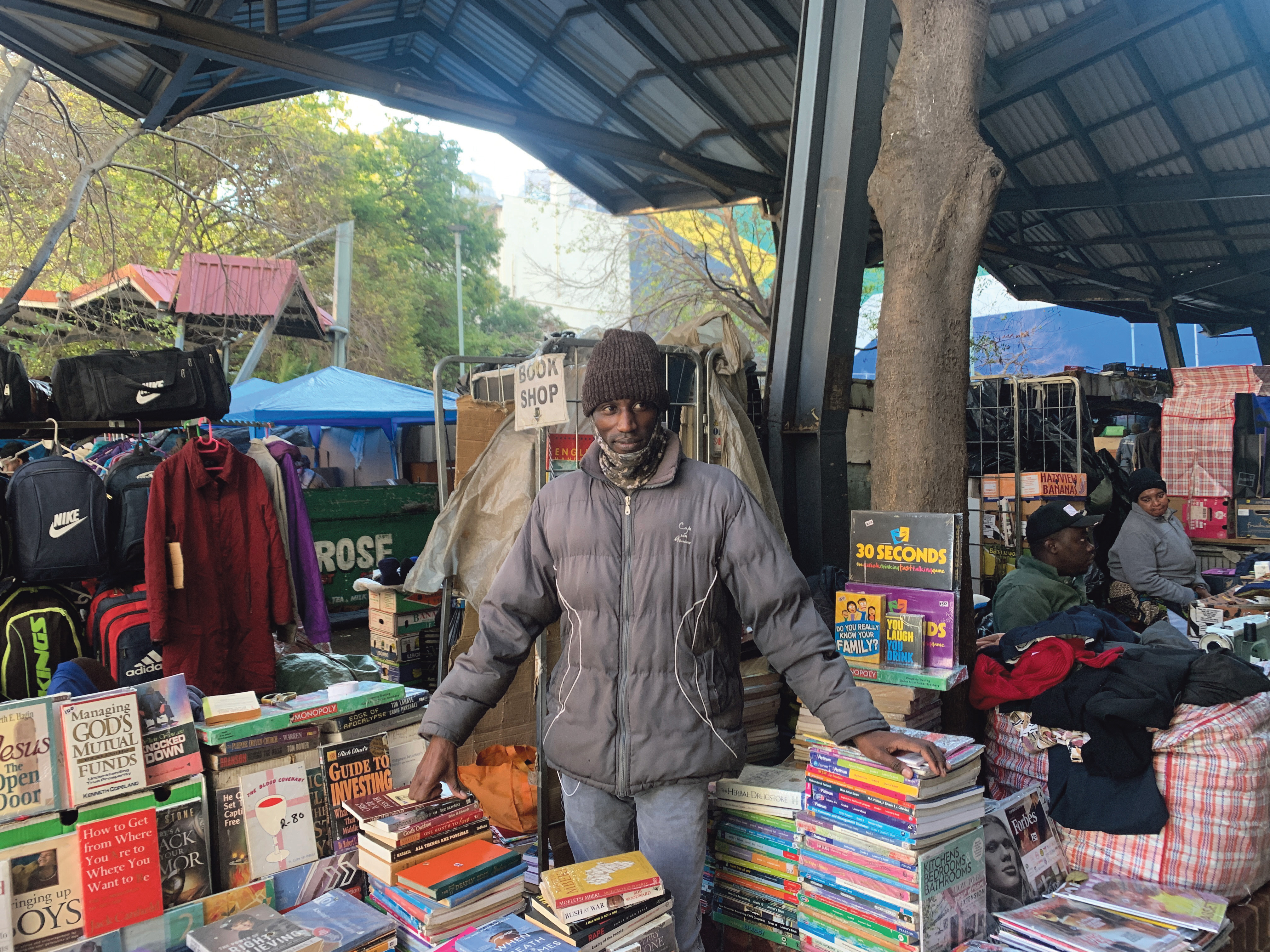

Present Njovo has been selling at his stand near Ernest Oppenheimer Park for two years. His love for books began with fashion and business magazines while he was growing up. (Photo: Yiming Fu)

Books sold by formal booksellers are also subjected to a value-added tax of 15%, which can put them outside most people’s budgets.

“Right now it looks as if black people do not read at all,” Mhlekwa says. “And that is not true. We just don’t have the resources.”

Shifting the story

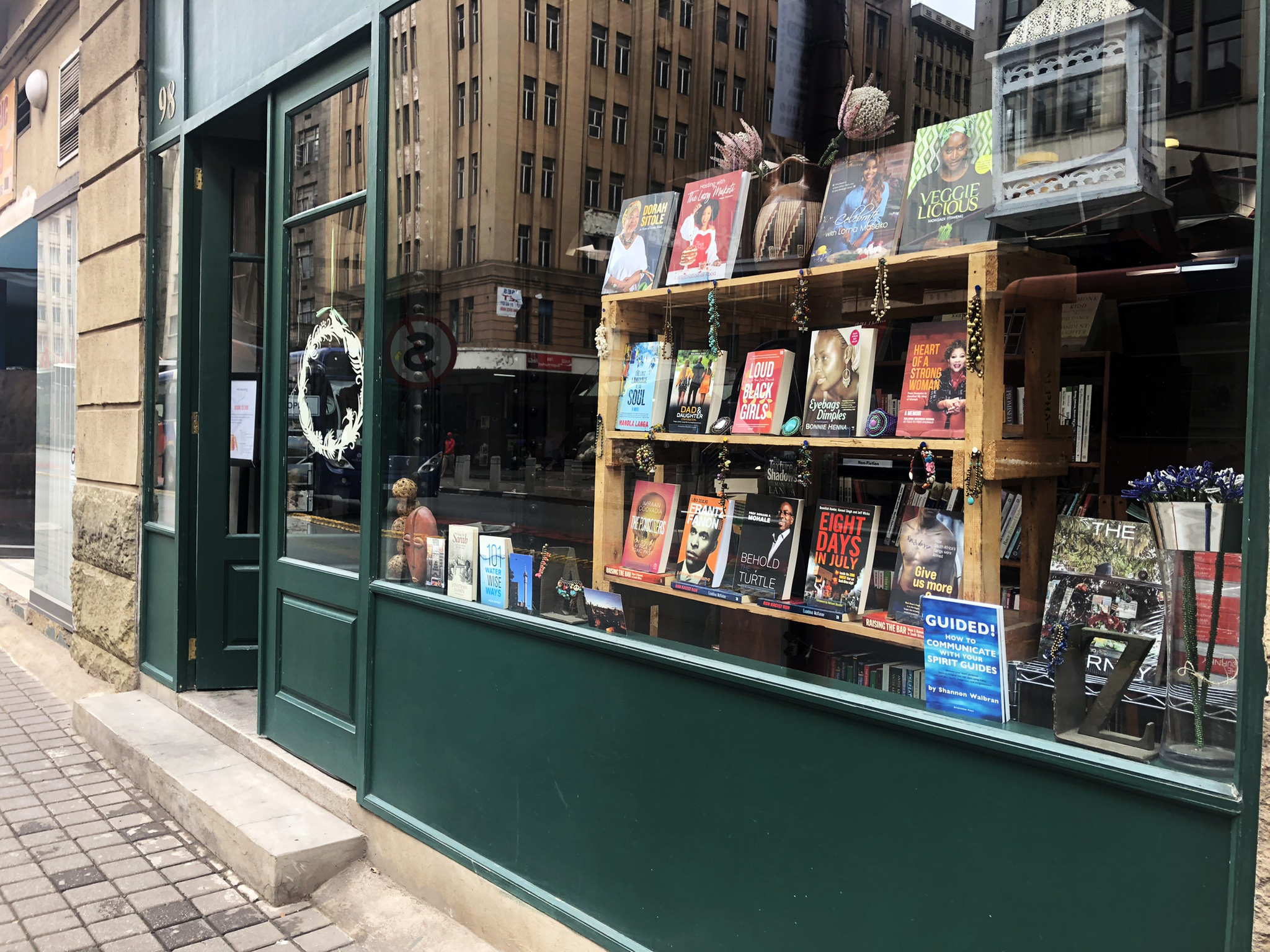

Griffin Shea, the founder of Bridge Books, partnered with the Johannesburg Development Agency a couple of years ago to do community outreach and rebrand parts of the CBD neighbourhood to the Johannesburg literary district to change the narrative of what the city is and what actually happens downtown.

“People love to tell a story that’s horrifying, like you have to be so tough to live here and everything is so gritty and intense,” Shea says. “But there’s this other narrative: we’re also a city that can support over 1,000 bookstores and have 60 of them trading in a 10-block distance.”

Bridge Books supports the informal booksellers by connecting them with publishers and getting them discounted books. It is also working to clean the Johannesburg City Library as well as parks in the area where it hosts story time with children every Saturday. The store is also developing a street libraries initiative in Soweto and Alexandra, which have huge populations and limited access to books.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Downtown is looking up – Joburg inner-city projects bring work and hope to its young residents

For the staff at Bridge Books, visibility is the key. Informal booksellers meet South Africans where they’re at in the busy city centre, mingling, shopping or just out for a stroll. They display a wide variety of books and can show readers how many options they have. Even if someone wasn’t looking to buy a book, they may stumble upon something that catches their eye and fits their budget.

Bridge Books on Commissioner Street in the CBD. (Photo: Bridge books)

The public park story times are also aimed at getting books to kids and sparking interest by meeting them where parents might take them.

“So it’s great if the books are being published,” Shea says. “But if no one knows that they’re there, or they’re available, and if they’re not part of the kids’ daily lives, then you haven’t really been inclusive or representative.”

The ups and downs of bookselling

Nwigwe says that though book sales are lower than they were before the Covid-19 pandemic, they are slowly on the rise again. Most of the informal booksellers in the literary district have seen similar trends.

Nwigwe doesn’t think sales will reach the peaks they used to because people use the internet more often to read books.

Present Njovo sells books at a stand near Ernest Oppenheimer Park. He’s been at the stand for two years and has been selling books for seven. His love for books started with business and fashion magazines growing up. School books and bibles are his most popular books.

See Daily Maverick’s bestseller lists by month

Henry Muho sells books and magazines near Park Station. His stand features more than 500 books, including academic, motivational and spiritual books. He says he sells about seven to 10 books a day, at prices that hover between R50 and R80. Magazines fly off the shelves the fastest.

“The best part is interacting with people,” Muho says. “The more you are selling books, the more you are interacting with other people and you want to know what other people are getting. So one way or another, you’re getting knowledge.”

For Nwigwe, reading is crucial for passing down knowledge, learning the history of the world and gaining the wisdom from people who came before you.

“We need to know where we are coming from,” he says. “It helps us to know where we’re going.” DM

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper, which is available countrywide for R29.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.