45TH ANTARCTIC TREATY CONSULTATIVE MEETING

Helsinki heatpocrisy: Overlooked Russian oil/gas hunt exposes chinks in Antarctic climate declaration

Melting region remains at risk as polar states fail to address key mining, species threats in the Finnish capital.

Helsinki, Finland — A crucial meeting about the endangered Antarctic wrapped in the Finnish capital on Thursday, 8 June, attracting minimal global attention — even from environmental NGOs. It was entirely ignored by most international media.

Over two weeks until last Thursday, Daily Maverick waited outside the closed-door meeting hall, ready to report on breakthrough developments about one-tenth of Planet Earth teetering on the edge of catastrophic melt and species extinction caused by human consumption of oil and gas. Despite their prolonged vigil at the conference centre, the 29 decision-making parties of the Antarctic Treaty failed to reach any significant agreements.

The only outcome was the non-binding Helsinki Declaration on Climate Change and the Antarctic, which “reaffirms” states’ commitment to the mining ban that has been in effect since 1998. And the laws they seek to uphold have not deterred decision-making party Russia from searching for Antarctic oil and gas.

The other parties with decision-making (“consultative”) powers attending the meeting included major states such as Australia, China, France, Germany, Norway, the UK, the US and South Africa (the latter also enjoying the uninterrupted power supply of the four-star hotel opposite the conference venue).

The Helsinki Declaration was not only an achievement, the Finnish hosts suggested, the meeting also attempted to tackle concerns about the expected 120,000 visitors to Antarctica during the upcoming summer season.

But closer scrutiny of the documents presented at the 45th Antarctic Treaty consultative meeting — which was closed to the public and where most diplomats refused to talk to the media on the margins — reveals oversights that continue to expose chinks in a mining ban still vulnerable to being lifted.

For instance, a “working paper” drafted by the United States, which to a lesser degree informs aspects of the Helsinki Declaration, fails to address controversial activities by some among them. This raises questions about how member states enforce the treaty’s Madrid Protocol to protect Antarctica, a reserve dedicated to peace and science for the benefit of the entire human species.

The 1959 Antarctic Treaty, of which Russia and South Africa are among 12 state founding signatories, sets aside the sweeping, but melting, deep freeze below 60°S as a natural reserve “in the interest of all humankind”. For its part, the Madrid Protocol describes the treaty’s environmental laws and its mining ban.

Without doubt, some of these laws stand as achievements in diplomacy and conservation, effectively prohibiting land ownership and nuclear explosions. As the rallying cry goes, they would be difficult to reproduce in today’s tumultuous geopolitical landscape.

But through detailed investigations first published in October 2021, Daily Maverick has repeatedly shed light on Russia’s ongoing pursuit of oil and gas in the Antarctic reserve, by using Cape Town as a launching point.

Despite bringing this to the attention of treaty authorities, and seeking their comment, there is as yet no record that these activities were discussed at the Helsinki meeting. The US-drafted working paper, which proposes reaffirming the mining ban, does not mention Russia’s mineral investigations.

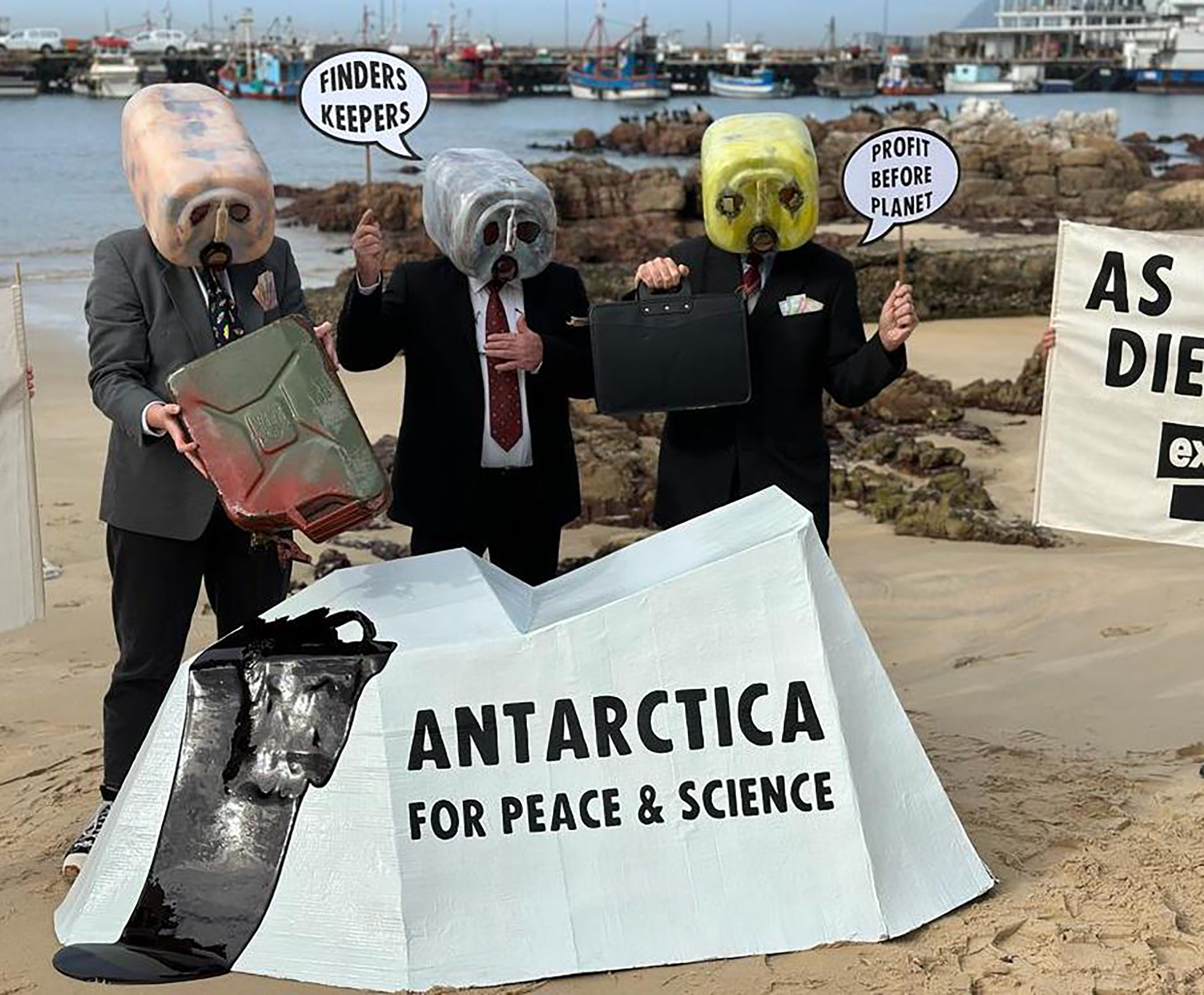

Campaigners gathered in Cape Town in January to protest against the arrival of the Akademik Alexander Karpinsky, a Russian Antarctic Expedition-flagged vessel. (Photo: Jamie Venter)

The working paper, introduced on the 25th anniversary that the mining ban came into effect, received co-sponsorship from a “record” majority of 24 out of 29 decision-making parties — basically the full sweep of major European and Western states.

But Russian allies Brazil, China and South Africa, and more surprisingly Western-aligned Ecuador, were not fellow co-sponsors.

South Africa’s authorities have been supplied with proof that they have allowed the Russian ship Akademik Alexander Karpinsky to pass through Cape Town, which has fired at least 140,000km in seismic blasts that may harm marine life, but they have been giving confusing and unclear answers.

Lisolomzi Fikizolo, head South African delegate to the Helsinki meeting, in a two-hour Antarctic briefing to Parliament’s environmental portfolio committee on Tuesday, claimed no one had delivered evidence of Russia’s fossil fuel-focused Antarctic operations.

We have consistently furnished the South African Department of Forestry, Fisheries and Environment with evidence. This is the same department that oversees South Africa’s Antarctic interests and employs Fikizolo. In the wake of our investigations, evidence has also been cited by a string of peer-reviewed publications, including the Royal Australian Navy, as well as 29 South African environmental groups, who sent a widely publicised letter of demand to Fikizolo’s employers. (Protests by these environmental groups in early 2023 made international headlines from London to Moscow, yet Fikizolo claimed no knowledge of the groups and their grievances.)

It is telling, perhaps, that the South African delegation, declining our in-person request for an interview in Helsinki, did not join Russia in giving an otherwise roaring standing ovation for a youth climate activist during the opening ceremony.

But spokesperson Peter Mbelengwa, responding to our queries, said the national department “would like to clarify that there are existing legal frameworks in place that prohibit mining activities in Antarctica” and that South Africa had “fully implemented” the protocol.

Ultimately, all states including South Africa supported the adopted Helsinki Declaration – but this climate document is merely hortatory: so it imposes zero legal obligations and is weaker than the proposed US-produced foundational draft on reaffirming the mining ban.

That foundational draft calls on all signatory governments — including Russia — to explain, publicly, why the mining ban is a really good thing, and that it is “a matter of highest priority” to uphold it.

In the final Helsinki Declaration, however, the countries hardly exceed basic expectations: they merely promise to stick to the rule that mining — including extraction — is not allowed (except for “scientific research”).

Oh yes, and they want everyone to know that the ban does not have an expiry date.

‘It’s a matter of principles’

The Helsinki Declaration rightly points out that the ban does not have an expiry date. It also alludes to a persistent frustration within the Antarctic diplomatic and academic community — one that is as enduring as the myth that fuels it: the mistaken belief that the ban expires in 2048.

As we have reported — for instance, here, here, here and so on and so forth — the mining ban does not have an expiry date.

But that does not mean the ban is immune to pressure or expiry.

Starting from 2048, any country with decision-making rights could request a review conference of the Madrid Protocol’s Article 7 (the mining ban), and thus also the negotiation of a new agreement. If the country does not like the results of the review? Then it (or more countries) can invoke the withdrawal clause and leave the party. This could pave the way for destructive mining activities in a wilderness already challenged by climate threats at this juncture in 2023.

It was the US who, ironically, had insisted on a potential expiration for the mining ban as a condition for signing the Madrid Protocol. Curtis Bohlen, the chief delegate of the US negotiating team, opposed a permanent ban in 1991, contending that future generations should have the right to decide.

“We have always been opposed to a permanent prohibition on Antarctic activities,” the US chief delegate told The New York Times. He was also George Bush Sr’s assistant state secretary for oceans, environment and science. “It’s a matter of principles. We should not foreclose the right of future generations to make decisions.”

In 1992, a now-defunct House of Representatives committee told their subcommittee colleagues they had pushed for an “indefinite” ban instead of a permanent one, to allow for the possibility of mining.

“The United States was prepared to agree to an indefinite ban on mineral resource activities, but refused to accept a permanent ban in the event minerals would need to be obtained from Antarctica in the future … The US insisted upon the withdrawal clause as a condition of signing the protocol.”

As Washington was also the 1959 treaty’s original proponent, and has been its depositary since then, we reached out to the US Embassy to South Africa to clarify discrepancies between the original drafters’ intentions and the apparent understatement of the fact that a permanent ban was initially regarded, at least by the US, as a matter of significant importance, akin to a violation of human rights.

Since the 2023 Helsinki working paper also singles out those “outside the Antarctic Treaty system” for “mistaken” beliefs, but makes no mention of those inside the system who may be using a fêted ban to look for fossil fuels, we asked the embassy for additional thoughts on Russia’s activities via Cape Town.

Recently, US Ambassador to South Africa Reuben Brigety had accused the South African government of supplying arms to Russia via the Lady R cargo vessel.

“The US maintains our strong commitment to preserving Antarctica for peace and science, and to protect its environment through the Antarctic Treaty system. All consultative parties adopted a resolution at the [meeting] in Helsinki to reaffirm the Article 7 mining prohibition, including that it does not expire in 2048 or any other year,” a US embassy official told us.

“It is significant that three-fourths of all consultative parties co-sponsored the working paper on this topic — a record number — and that all consultative parties supported this resolution,” according to the official. “This further demonstrates how strong the global commitment is to preventing commercial mineral extraction, including fossil fuels, in the region.”

Science vs prospecting

Kremlin mineral explorer Rosgeo has repeatedly told us the Karpinsky’s work conforms to the mining ban’s scientific allowances. But it has also stated its intentions to exploit Antarctica’s mineral resources through its self-declared, unmatched search for oil and gas in the Southern Ocean.

In 2017, Rosgeo noted its long-term operations in Antarctica were “aimed at studying the geological structure and mineral resources of the Antarctic” and “are of geopolitical nature”.

According to its subsidiary, “they ensure guarantees of Russia’s full participation in any form of possible future development of the Antarctic mineral resources — from designing the mechanisms for regulating such activities up to their direct implementation”.

Rosgeo is the Kremlin’s “key contractor” within “the state order for reproduction of the mineral resource base of the Russian Federation”.

It is a resource company. And, together with its Antarctic subsidiary, it has made numerous, even extraordinarily brazen, pronouncements about Antarctica’s oil and gas in recent years, such as openly confirming its annual assessment of the Southern Ocean’s hydrocarbon “potential” and claiming there are 500 billion barrels of oil and gas beneath those waters.

‘New Zealand did not comment’

Ahead of the Helsinki meeting, a city hall public seminar took place on 29 May, jointly organised by different entities, including the Finnish foreign ministry. Jana Newman, head of the New Zealand delegation, did not say anything about Antarctic oil and gas interests during a panel discussion that ventured into ban politics.

We have also presented evidence of Russian activities to the treaty’s environmental protection committee — of which New Zealand is a member. In our efforts to gather information, we have contacted several committee members for comments and interviews, both through email and in-person interactions during the Helsinki meeting.

The #AntarcticTreaty Consultative Meeting XLV and the Meeting of the Committee for Environmental Protection XXV, which took place in Helsinki from 29 May to 8 June, have concluded.

➡️ https://t.co/dGBhfYafAn#ATCM45 #CEP25 #AntarcticaProtected #InternationalCooperation 🇦🇶 pic.twitter.com/VnHPOeIgTe

— AntarcticTreaty (@AntarcticTreaty) June 9, 2023

Praising the Madrid Protocol’s “remarkable” achievements, Newman then responded to a Daily Maverick question about what the treaty’s exclusive environmental observers — the Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition (Asoc) — had done to promote a proposal paper on an unmodifiable ban at the 2022 Berlin treaty consultative meeting.

This proposal references peer-reviewed work that cites Russian Antarctic prospecting, and the Berlin meeting minutes say the proposal was tabled, but there is no evidence that it was discussed.

“[The protocol] has an unequivocal and unending ban on mineral resource activities and so, in response to an earlier question, with respect to Asoc’s paper, New Zealand did not comment on the need for a ban because we have an indefinite and unequivocal prohibition on mining in Antarctica — and I think it is something that we should all be proud of and be clear in our articulation,” Newman said.

Articulation means different things to different people.

When asked by Daily Maverick, senior Russian geology academia also involved in scientific papers sizing up the Antarctic’s oil and gas potential would not wipe the option of Antarctic mining off the table — despite the Kremlin’s falling oil and gas revenues amid its war against Ukraine.

They suggested that the Madrid Protocol “banning exploration in Antarctica is a gentleman’s agreement”.

Chinks in the armour

The Helsinki Declaration addresses ice-sheet loss, rising seas and impacts on coastal humans. But the working paper drafted by the US questions the need for stronger measures to reinforce the existing ban.

There is an “erroneous belief” that “action is necessary to maintain Article 7”, the working paper says.

These kinds of claims neglect a vital aspect of protecting this vulnerable region, says the Antarctic governance expert Professor Alan Hemmings, who in 2022 co-wrote the first peer-reviewed call for an immediate, “forever” ban on oil and gas extraction in the region.

What Hemmings and co-author Dr Patrick Flamm wanted — in other words — was an evolved ban that could never be changed or, a worst-case scenario for many, lifted after thrashing out a mining pact based on majority support.

A high bar, many say, but an Antarctic governance authority at New Zealand’s Canterbury University, Hemmings himself told us that commentators such as New Zealand chief delegate Jana Newman “miss the point” — especially on hydrocarbons, the building blocks for oil and gas.

When the Madrid Protocol was signed in 1991, becoming enforceable towards the end of the decade, “the time horizon of 2048 was a very long time ahead — 50 years. We are now halfway through that period, and there has been no progress on other outstanding work from the Madrid Protocol,” laments Hemmings. He cites the failure to bring into force the 2005 agreement that would hold perpetrators responsible for unleashing possible Antarctic environmental emergencies. This agreement was adopted as the Madrid Protocol’s Annex VI.

“There is clear evidence that states are looking at hydrocarbon extraction from Antarctica,” he says, “including, as Daily Maverick has documented, prospecting activity by the Russian Federation.”

‘Neither unequivocal nor unending unless we make it so’

A litany of subsequent international accords such as the Paris Agreement, and unfolding evidence of the climate emergency, underline that the ban’s generic minerals focus obscures the really pressing challenge of heading off hydrocarbon extraction, and doing so as soon as possible, Hemmings contends.

“Difficult it may be, but there is no reason to think that fast-changing Antarctic geopolitics is going to make it any easier in five, 10 or 25 years’ time. There is indeed no obligation to lift the minerals prohibition after 2048, but it can be done, and that is the worry,” says Hemmings.

“There is a world of difference between the prohibition being open ended, as it is; and an ‘unequivocal and unending ban’, as Ms Newman mistakenly asserts on behalf of New Zealand,” he adds. “Sadly, it is neither unequivocal nor unending unless we make it so. It requires effort now to close off the most [problematic] of all minerals activity, the extraction of Antarctic hydrocarbons, not kicking the can down the road and trusting to a wing and a prayer after 2048.”

If no one is planning to excavate the fragile, difficult-to-mine and far-flung Antarctic, why not just get rid of the 2048 review clause that is arguably the main agitator of all that confusion, noise and annoyance in the first place?

For Hemmings and Flamm, a similar solution already exists.

A “Measure” — a legally enforceable decision removing any options to consider oil and gas mining at any point in the future — had been immediately available to both the Berlin and Helsinki meetings.

If these proposals presented a window of opportunity, that opportunity has now been handed to India — whose Antarctic staff marked Russia’s “Victory Day” of World War 2 (“Great Patriotic War”) at the Russian station Progress on 9 May. The Indian government, hosts of the 2024 treaty consultative meeting, is known to have co-funded Vladimir Putin’s war machine by buying his oil and gas.

‘That’s what NGOs are funded to do’

It was Asoc — the treaty’s invited environmental observers — that submitted a “Measure” paper at the Berlin meeting drawing on the Flamm and Hemmings proposal. The only non-profit coalition allowed behind the meeting’s closed doors each year, the group would also outline that mechanism to make the ban unchangeable — although Asoc Executive Director Claire Christian, in an emailed correction, conceded the group had not attempted to advance their proposal.

A World Environment Day ‘artivism’ protest by Extinction Rebellion Cape Town in the southern suburb of Kalk Bay. (Photo: Ethan van Diemen)

“I am afraid I misspoke when you asked me a question during the panel today,” said Christian, referring to the Helsinki city hall discussion in which New Zealand’s Newman took part. “We did not introduce our mining ban paper formally at the meeting last year, however it was submitted to the meeting for all delegates to read. I sincerely regret the error. I do not personally introduce every paper at the [meeting] and I am not in every session (there are often parallel sessions) and so I should have double checked instead of answering right away.”

Recently, during a live webinar, a senior Asoc member told us they were wary of raising Russian oil and gas activities in Antarctica and criticising the treaty system — in the potential event that this threatened their embedded position in the room.

While criticising the Helsinki event for missing pivotal targets, but pinning their hopes on the Chile meeting on marine protected areas kicking off 19 June, Asoc refrained from revealing the troublemakers due to the closed-door policies. This brand of criticism has previously garnered attention from Twitter commentators, including Professor Anne-Marie Brady, a polar specialist at Canterbury University who has written extensively about China’s potential involvement in Antarctic mineral resources.

“Why are Antarctic NGOs so timid nowadays? Greenpeace was once a thought leader in Antarctica. ASOC now afraid to name the 2 states who were spoilers at the [Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources]: China & Russia, both opposed to environmental protection,” Brady tweeted in November 2022 after the Tasmania fisheries and conservation meeting. “You can’t persuade them [China and Russia], but that’s what NGOs are funded to do.”

Dr Salleh Mohd Nor, chief Malaysian delegate of the Sultan Mizan Antarctic Research Foundation, told us on the sidelines he wished to see ‘greater global participation’ in treaty meetings. (Photo: Tiara Walters)

Not all NGOs active in Antarctica are “timid”.

In the first quarter of 2023, Sea Shepherd and the Bob Brown Foundation ventured into the Southern Ocean to document “destructive” krill fishing, and suggested more expeditions would be on the way.

On 5 June (World Environment Day), Extinction Rebellion staged its protest in the Antarctic gateway of Cape Town. This was the latest in a series of coastal demonstrations against Russian oil and gas activities.

With Greenpace Cape Town volunteers and 27 other South African environmental groups, this coalition has called on the national government and other treaty parties to beef up the ban’s changeable nature.

They also contend that the public deserve transparency and honesty regarding Antarctica’s no-mining laws.

ICYMI because the #IceCurtain, the annual international @AntarcticTreaty meeting wrapped up on Friday, its anachronistic secrecy rules again failing the global public. Documents of #ATCM45 are here: https://t.co/LWlRmNin8V 🧵 pic.twitter.com/aFlKv6o65W

— Andrew Darby (@looksouth) June 11, 2023

The treaty secretariat had released all discussion documents — but not the meeting minutes — by Friday, 9 June after the meeting closed in Helsinki. But, as Antarctic commentator, journalist and author Andrew Darby has pointed out, “information delayed is information denied”.

Ice wide shut

If this was how the latest treaty consultative meeting, which is of global public interest, unfolded, there were no international reporters to tell anyone about it.

Finland attempted to increase media access, Finnish Polar Ambassador Tiina Jortikka told us, but some countries opposed exposing confidential matters.

Next year’s meeting host, India, ranks 161st on Reporters Without Borders’ 2023 World Press Freedom Index, just three places ahead of Russia. DM

Tiara Walters is a full-time reporter for Daily Maverick’s Our Burning Planet unit. Walters’s travel to Helsinki has been made possible, in part, by the support of the Friedrich Naumann Foundation and the Finnish Embassy to South Africa.

To read all about Daily Maverick’s recent The Gathering: Earth Edition, click here.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.