BOOK EXTRACT

Bullet in the Heart: Four brothers ride to war 1899-1902

Four Muller brothers, Michael, Chris, Pieter and Lool, fought in the Anglo-Boer War against the British. Three of them kept diaries. When Beverley Roos-Muller first began to explore writing about the Boer experience of the war, she read the tiny war diary of Michael, grandfather of her husband, Ampie Muller. It led her to the discovery of the other diaries and many more documents. Bullet in the Heart is published by Jonathan Ball.

“It is nine months this evening since I last saw the light in my own house, when I had to tear myself away from all that is dear to me. And today is also my little son’s birthday. Oh, how I long for home.”

So wrote Michael Muller in 1901 as he gazed at the lights of Cape Town from a ship bound for Bermuda, after months of internment in a British POW camp in Simon’s Town. The camps were full, so Boer prisoners were being sent to other parts of the empire. Michael’s brothers, Chris and Pieter, were exiled to Ceylon, while Lool was held in the Green Point camp in Cape Town.

Remarkably, three of the brothers kept diaries — the only known instance of this happening in the Boer War. They recorded their intimate thoughts and turbulent emotions, and the diaries gave them agency. The scrawled notes of Chris on the evening after the legendary Magersfontein battle, the rain-dashed pages written by Lool in Colesberg, and the angry words penned by Michael about his treatment at Surrender Hill, have the urgency of men determined to go on record.

In this extract, Michael Muller is sent into exile in Bermuda.

*****

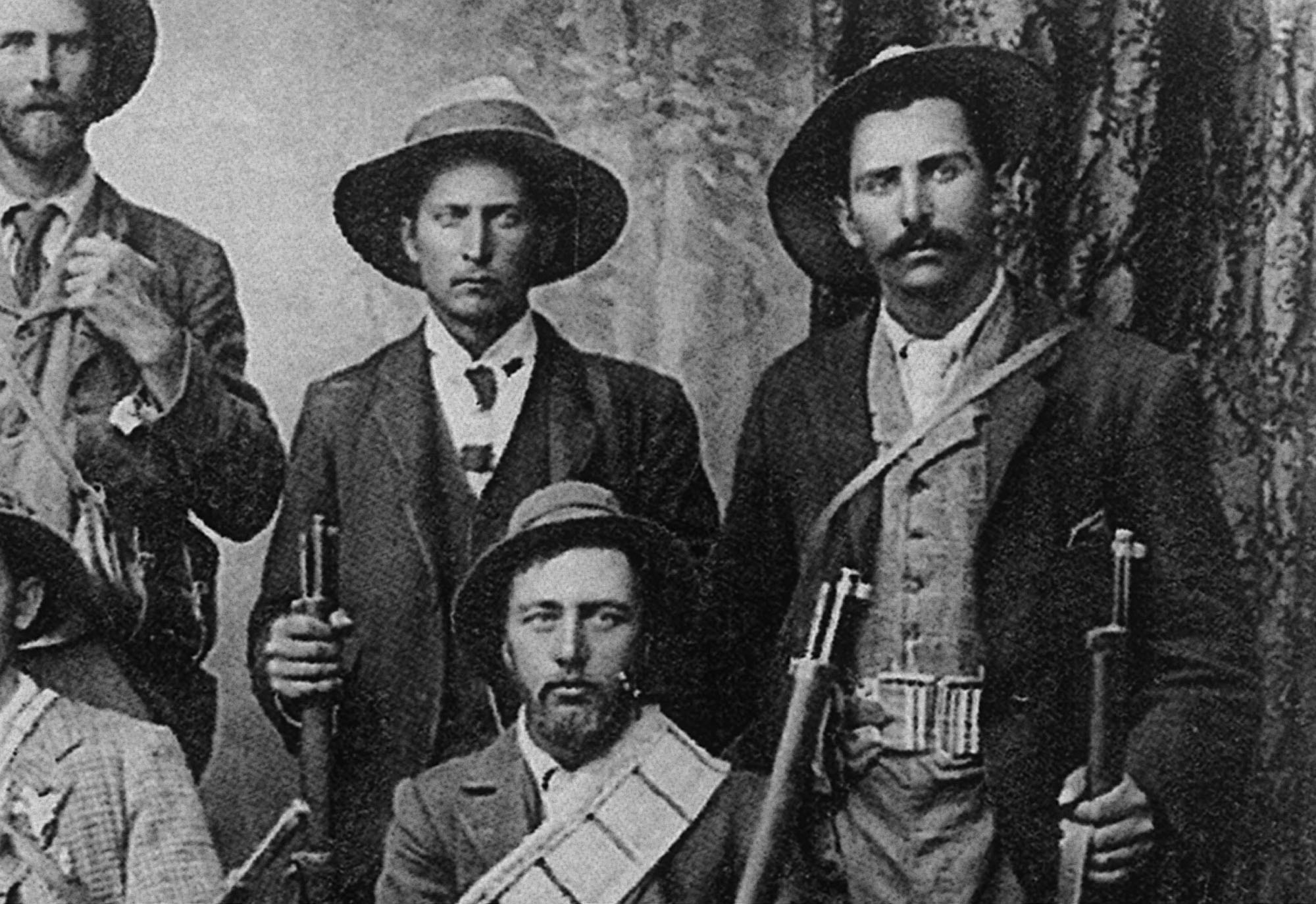

Pieter (middle back) and Chris Muller (back right). (Photo: Supplied)

The cargo ship on which Michael had endured his unspeakable journey across the Atlantic from Cape Town dropped anchor in Grassy Bay, Bermuda, on 28 June 1901. A crane and a basket, used when there was no quay available, offloaded four men at a time. This, and offloading the cargo on board, took several days, hence the discrepancy between Michael’s diarised date (1 July), and their official date of arrival.

He spent the rest of his war — another full year — on Darrell’s Island, hardly any distance at all from the Bermuda mainland; it was one of the camps of the Bittereinders. Quiet Michael may not have been a man who “made waves” but he was a man of sturdy principles, even when it cost him dearly.

His new home was a small, narrow strip of land less than half a mile in length — not much space for so many prisoners. This cramped island was further divided into two by a high barbed-wire fence, one side for Boer prisoners, the other for their guards. The fence threaded through abundant tall trees, native cypresses and cedars, which provided wood as well as natural shade. Where fence met sea, wooden poles were set in concrete so that the barbed wire extended some way into the water. Between the two sections there was a single, tall iron gate, topped with long angled spikes. Wooden “sheds” were used as pontoon latrines on rafts, floating just offshore and reached by a gangplank. It doesn’t bear contemplating what that shoreline was like after a thousand men had completed their morning visit.

*****

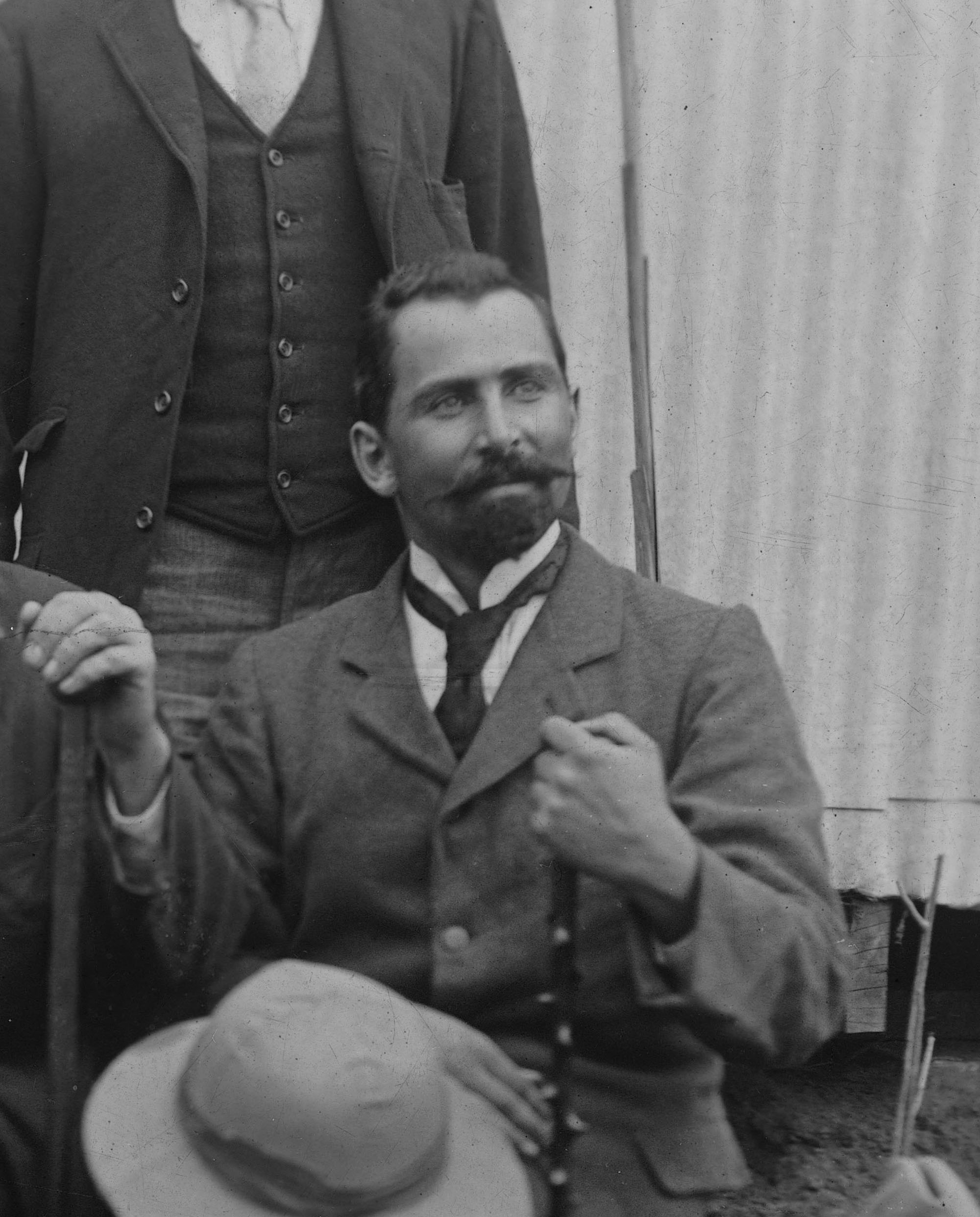

Lool Muller. (Photo: Supplied)

Boer prisoners were exiled in their thousands to British colonies: first to the nearest, St Helena (almost 6,000 in April 1900 alone); then to Ceylon; and later, more than 9,000 to India. Even Portugal entered the fray, owing to the many Boer refugees in then-Portuguese East Africa (today Mozambique) — these 1,500 men, women and children were held in open camps in and around Lisbon, and were treated as parolees.

Bermuda was one of the last colonies to be ordered to accept prisoners; they could hardly refuse, but it was a thorny issue. The 17,000 residents of Bermuda were not exactly thrilled to discover that they were about to have thousands of Boer prisoners foisted on them. This small, pretty cluster of islands relied on tourism as its main revenue then, as now. It has a subtropical climate, balmy seas and relatively good weather — apart from the major drawback of it being in the “hurricane belt”. Water was one of the legitimate concerns of Bermuda residents, just as it had been in Simon’s Town, particularly as Bermuda was experiencing its most severe drought in 30 years.

Michael was in the first shipment of Boer POWs to Bermuda. The canny governor made no mention of their imminent arrival during a debate in May 1901; he waited until the ship had actually dropped anchor before passing martial law.

Residents were slightly mollified on hearing that the Boers would not be kept on the mainland of Bermuda, but on the many little coral islands just offshore, within the curve of the Great Sound: Darrell’s (not even a mile from the shore, it housed the main telephone exchange connected to all the other islands including the guard-post on the mainland), Burt’s (the smallest island camp, set aside for the most resistant bittereinders, plus 27 Boer officers, on whom the authorities kept a beady eye), Hawkins’, Port’s (on which there was a hospital), Morgan’s, Tucker’s (to where Boers who signed the oath of neutrality were immediately transferred for their own protection; this group eventually numbered 800, and received no special privileges) and Hinson’s (for about 200 Boer boys aged, disturbingly, 6 to 16; a school was built here for them but only completed in April 1902, barely a month before the war’s end). Some of the islands were so close that if they shouted, men on the next island could hear.

In the year up until the war ended, just over 4,600 Boer POWs were shipped to Bermuda’s little water-bound prisons. Thirty-five of them died during their captivity, mostly of infectious diseases such as typhoid or pneumonia.

The spokesman for the Boer POWs on the islands was Commandant Pieter Ferreira of Ladybrand — one of the many Ferreiras from the Free State. The arrival of Boer “convicts” — citizens of the Cape Colony who had been convicted of treason against Britain — caused another outcry in Bermuda.

Some of these soldiers had been sentenced to death and had their sentences commuted. They had travelled to Bermuda wearing the same prison uniforms they had worn in the Cape, with heart-shaped targets sewn onto the front of their shirts, indicating where the firing squads should aim.

The first of these so-called “convicts” arrived on the ill-fated Montrose in 1901, and then another, much larger batch of 250 more on the Harlech Castle. They were forced to work in the quarry on Long Island, to which they were marched across wooden footbridges each day from Hawkins’ Island. They were not allowed to receive post or money, and had no access to tobacco.

Their clothes and shoes were pitiable, and the food and water they were given was not enough to sustain them in their hard labour, so they tried to find ways of earning a little cash by making and selling handicrafts to the mainland.

The POW Ladybranders on Darrell’s Island in Bermuda, 1901. Michael is third from the left in the front row, No 14, with his hand on his knee. Each number was rewritten on the back of the photograph, and signed by that POW. The photo was then sent to their commandant, Chris Muller, captive in Ceylon. (Photo: Supplied)

Once Bermuda residents got used to the idea of having Boers present, they were treated as something of a spectacle. Sunday afternoon trippers, the women dressed in white with Panama hats and parasols, were rowed over to ogle the newly arrived prisoners. The mood of the residents was on the whole peaceable, and in a few cases actively supportive, for some local families had originally arrived from the United States, which had its own grievances against its former British colonisers.

The several small islands to which the Boers were allotted were low in the water — in fact, some of them, such as Burt’s, disappeared after the war. In a particularly high spring tide or during hurricane weather, they could be swamped, causing panic among the prisoners.

The issue of water was managed by pressing Nelly Island into service: it had a large water catchment with storage tanks, and supplied other islands when their catchments ran out. Each prisoner was given adequate drinking water but it meant that clothes — and themselves — had to be washed in the sea.

Any thoughts of swimming to freedom were countered by armed guards ordered to shoot, as well as the abundant sharks; Royal Navy vessels patrolled, armed and equipped with searchlights. A few succeeded, nonetheless, for the mainland was close. A reward was offered for escaping prisoners.

A youngster was shot dead one night, on 28 April 1902, as he tried to get through the wire. The shooting of this 16-year-old did not provoke the same outrage among the Boers as the deeply controversial death of Philip Cronjé in Green Point camp; they seem to have accepted that being shot while escaping was a part of war.

Despite how hard prison is on the human spirit, irrepressible nature will burst out. The men on Darrell’s Island, for instance, one night launched a life-size dummy on a raft made of tent floorboards, with the name “Joe Chamberlain” (the British minister behind the war) attached to it. The searchlight of a patrol boat picked it up. The next morning the Boers spotted the dummy perched on top of one of their tents, without a word having been said — a case of practical joking on both sides.

From Darrell’s, Michael could easily see across the narrow stretch of ocean to the mainland of Bermuda, and the sweeping beam from the tall lighthouse on Gibb’s Hill which commanded an excellent view of the whole area, as well as of the POWs. And despite the danger from the searchlights and guns and sharks, some young men did take a chance and swim to nearby prison islands at night — to visit their friends.

As in all POW camps, filling the unforgiving hours was a central problem — how to alleviate the endless boredom. Exile is the existential “now” repeated daily, a length of leaden time. Each day brings anew its burden — the same boring repetition as the day before, and the next.

On Darrell’s Island, a large tent was erected for worship; daily devotions and hymn singing was commonplace. That was all very well, but the Boers were active people used to full days of work on their lands, or in their offices and other workplaces. They needed to be busy.

Help came promptly from the wealthy and fearless Anna Maria Outerbridge, who lived in Willoughby, an impressive colonial mansion sited on a rise in Bailey’s Bay on the main island. She was chief trumpeter among several organisations to aid the Boers and relieve their endless monotony.

Within a week of the first POWs’ arrival, the Association for Boer Recreation, supported by the governor, had distributed books and magazines, fishing lines and playing cards. Boer relief groups in the United States and the Netherlands collected clothing and money. The POWs particularly appreciated the books, in English and also in Dutch, German and French.

Willoughby was unabashedly a pro-Boer haven, and as Miss Outerbridge’s reputation spread among the POWs, escaping prisoners sought refuge there. (Her views enraged many Bermudians; they took revenge on 5 November 1901 by burning her in effigy instead of Guy Fawkes.) The authorities were well aware of this, and if any men went missing, the first thing they did was descend on her house. The exasperated government of Bermuda passed a law with her in mind, making it an offence punishable by up to five years in prison to aid or harbour POWs. It had absolutely no effect.

Luckiest were those POWs skilful in using their ubiquitous pocket knives.

The crafts were eventually sold in every curio and tourist shop, earning useful money. Using whatever materials came to hand, they made walking sticks, pipes, boxes of all sorts and sizes, picture frames, napkin rings carved out of bone, and delightful tiny carved “snake-shoes” — when you slid back a lid on top, a little carved snake popped out. Clever miniature pen knives were made from beaten coins, and playable musical instruments such as violins and bugles were carved out of cedar.

Chris Muller. (Photo: Supplied)

Michael made a small box in rich-coloured wood, likely cedar. He also made frames, one of which has “Bermuda” carved into it, as well as a date, “14.4.1902”; these items were brought home and inherited by some of his grandchildren.

Exercise was essential to keep the men occupied and fit, for inactivity could lead to depression. There was a rather eccentric croquet court on Darrell’s, while cricket was played on Morgan’s (the officers’ site), as well as Hawkins’, and among the schoolboys on Hinson’s; football was played too. Sports days were organised. Tiny Burt’s Island had quite a good tennis court.

Darrell’s Island boasted a piano, bought by some men who clubbed together to pay for it. Each island had its own choir, and enthusiastic singing could often be heard across the water.

Burt’s Island was so small that, except for the tennis court, there was no space to do anything except fish and swim. The inhabitants made up for it by producing a weekly newspaper, Die Burt’s Trompet, cobbled together from snippets of smuggled information.

Food was, of course, central to the men, as always in prison camps.

According to now-settled custom, they took turns cooking over open coal fires, though sometimes a cook was skilled enough to be pressed into service for the duration. It was a monotonous but fairly adequate diet of bread, potatoes, turnips, some beef (carefully weighed out), and canned milk, sugar, tea and coffee, but vegetables were hard to come by. When fresh vegetables were not available, lime juice with sugar was issued, the lessons of scurvy having been learned by the maritime British.

Bacon was issued once a week. Their main meat supply was large (10-pound) tins of mutton, routinely rolled out each week, called “horse meat” by the prisoners, who quipped that it must have come from the “biggest sheep” they had ever heard of.

Prisoners were allowed to buy items from the prison canteen — coffee, tobacco, matches, sweets and treats, stationery and stamps, and fresh fruit when it was available — but it was considered expensive.

Liquor was banned in the camps by a majority decision of the men themselves.

A few enterprising prisoners set up coffee shops, a prime example being the Lion’s Den on Burt’s.

The children on Hinson’s were served cooked food, cocoa served up “morning, noon and night”, and their favourite, condensed milk, freely available. A vat of ice cream was donated by residents of Hamilton, Bermuda, who ferried it over to Hinson’s and enjoyed seeing the boys from the “veldt” tasting it.

For Michael, each day brought its burden; the escape of dreams gave way in the dawn’s light to the clamour of unfamiliar voices and sights. Never had he thought he would long for Bellevue back in the Cape, but his memory of that roomy camp, with its lovely views of sea and mountain, the daily swim off a pleasant beach, the proximity to the familiar — all these became more precious for their loss. Men who had never seen the sea before the war were now, literally and alarmingly, precisely at sea level; storms swamped the shallow shores and threatened their billets. It was disconcerting, hot and foreign.

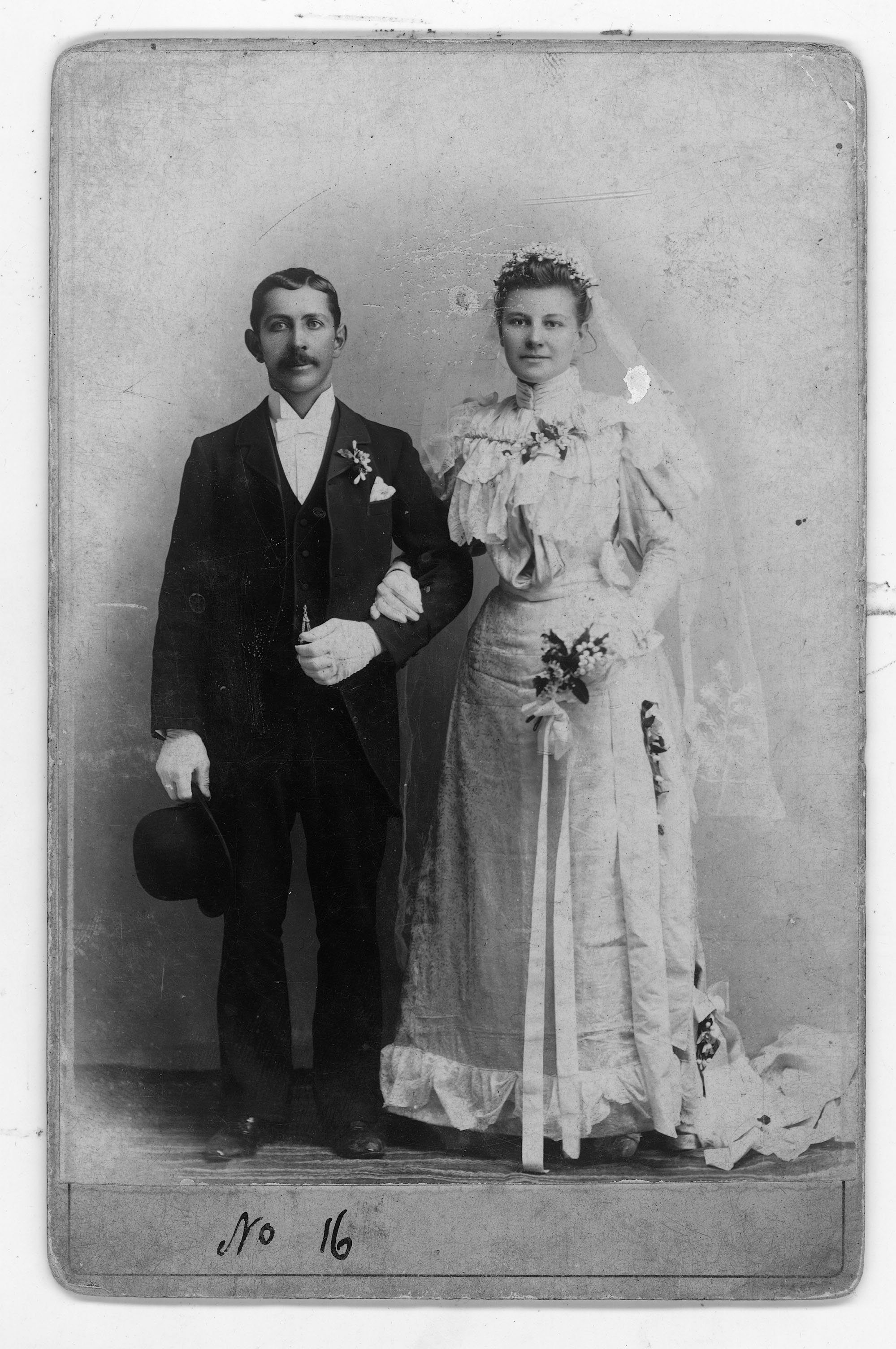

Michael Muller and Nelie (van den Heever) on their wedding day, 4 June 1895. (Photo: Supplied)

Post was the most prized item of all, and news that a ship had come in from South Africa always created a heightened atmosphere. Apart from the poor “convicts”, who were never allowed post, there were no restrictions on the amount of mail a POW could send or receive — subject, of course, to the snip of the censor’s scissors. A letter exists from Chris to his brother “Miki” with much of the page neatly clipped out.

It is fascinating to ponder the resilience of war letters, entrusted to remote postal services, crossing seas, enduring the challenges of weather and the vagaries of war. Yet here they are: little, neat envelopes, careful letters penned on fragile paper, precious words that reached loved ones, and now connect the centuries. DM

Dr Beverley Roos-Muller is a veteran journalist and broadcaster, and former academic lecturing in humanities at the University of Cape Town. She was an anti-apartheid activist in the 1980s, including being a spokesperson for the multi-organisational Open City campaign opposing the Group Areas Act. She is the co-author, with her late husband, Prof Ampie Muller, of Vuur in Sy Vingers about his father-in-law, the poet NP Van Wyk Louw.

Comments - Please login in order to comment.