THE READING LIST

‘She absorbed his raw hatred’ — Winnie Mandela’s five-day torture ordeal

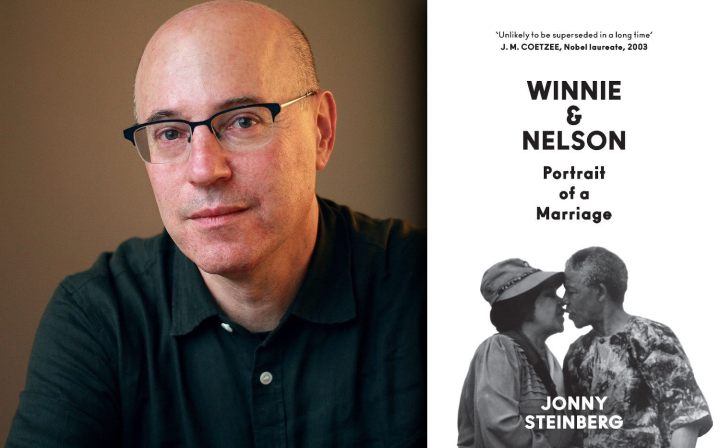

In this excerpt from ‘Winnie and Nelson: Portrait of a Marriage’, Jonny Steinberg explores Winnie Madikizela-Mandela’s ‘forensic’ account of her five-day torture at the hands of the lethal ‘sabotage squad’ member Theuns Swanepoel.

Winnie and Nelson: Portrait of a Marriage, by scholar and award-winning author Jonny Steinberg, delves into one crucial area of Nelson Mandela’s life that remains largely untold: his marriage to Winnie Madikizela-Mandela.

During his years in prison, Nelson grew ever more in love with an idealised version of his wife, courting her in his letters as if they were young lovers frozen in time. But Winnie, every bit his political equal, found herself increasingly estranged from her jailed husband’s politics.

Behind his back, she was trying to orchestrate an armed seizure of power, a path he feared would lead to an endless war. Steinberg tells the tale of this unique marriage — its longings, its obsessions, its deceits — making South African history a page-turning political biography.

Steinberg will be in South Africa to promote his new book, attending the Franschhoek Literary Festival and the Kingsmead Book Fair, and on tour in Cape Town and Johannesburg between 19 and 29 May. Read an excerpt of the book here.

***

What happened to Winnie during her interrogation?

Winnie wrote an affidavit recounting her interrogation five months later. It does not offer a transparent window onto what happened; nobody’s account of their own torture ever can. But it does have an important virtue. Her aim in telling the story was not to mythologize it for a wider audience. Her lawyers asked her to tell the story as forensically as possible, focusing on every detail. And this she did.

The interrogation began on May 26, two weeks after she was detained, and went on continuously for five days. Whether because of her fame or for fear for her health, she was permitted to sit on a chair for the duration. Nor was she beaten. But she was not allowed to sleep. Whenever she drifted off, a police officer would clap his hands loudly next to her ear, jolting her awake. By the third day, she had grown ill; her hands and feet were swollen and blue, her heart was palpitating, and she suffered from dizzy spells.

Her chief interrogator was a man named Theuns Swanepoel. Until early 1963 he had been a uniformed officer in the Flying Squad, the police’s rapid response unit. Along with dozens of others, he had been recruited at immediate notice into the security police, given a three-week course in political policing, and set to work. By May of that year he was one of the leading members of the “sabotage squad”, interrogating political detainees. He would most likely have partaken in torturing Brian Somana, along with the dozens more detained in May and June 1963.

By the time Winnie was jailed, Swanepoel had become a mythical figure in the ranks of the anti-apartheid movement. In his physical attributes, he was a torturer one might find in the pages of a nasty comic book. “The most outstanding feature about him was his ugliness,” Joel Carlson wrote. “His face was pockmarked, blotchy pink and purple. His nose was flabby with wide, flat nostrils. His ears stood out from his head beneath his close-cropped ginger hair and his head sat on his shoulders as if he had no neck.” But if he was ugly, he was by no means stupid. In the memories of some – although certainly not all – he possessed a lethal combination of traits: on the one hand, a genuine curiosity about what lay in the depths of the human being he had captured; on the other, an unrestrained appetite for cruelty.

Mac Maharaj, for instance, was captured in 1964, in his head the names of every single member of the South African Communist Party active in the country. He was desperate to divulge nothing. Swanepoel made a grand entrance, Maharaj recalled. “That was his style. He would walk into the room in the middle of an interrogation and the torture would stop. There would be a great sense of drama around his entry, and, usually, if you had not met him before, he would walk up to you, look you in your face, and ask: ‘Do you know who I am? I am Swanepoel. Do you know now who I am? Do you know what to expect from me?’ ”

Swanepoel had clearly given some thought to the encounter before he came into the room. Knowing that Maharaj had one good eye, he lit a match to it. Fearing that it would burn into its socket and that he would go blind, Maharaj panicked; he only just held back from talking, he recalled.

The following day, Swanepoel tried something else. Maharaj was taken to his office and told to strip naked and to put his penis on the desk. “Then [Swanepoel] took a policeman’s baton and started to stroke it, without ever taking his eyes off me, and then he raised the baton and brought it whacking down on my penis.” When Maharaj’s agony began to subside, Swanepoel stood him up and ordered him to put his penis on the desk again. “But this time, he did not hit it immediately. He picked up his baton, raised it, and waited for the expectation of pain to capture me before he hit.”

Day upon day, the ritual went on. Maharaj was taken to Swanepoel’s office and ordered to put his penis on the desk. On some days, Swanepoel left Maharaj’s body unscathed; he just stood there, the baton hovering in the air over the exposed penis all afternoon. Maharaj understood that were he to break, it was the expectation of pain, not the pain itself, that would do it.

And then, all of a sudden one day, Swanepoel did something new. He picked a badly beaten Maharaj off the floor, stood him against the wall, pressed the tip of a sword to his throat, and demanded that he talk. Trying desperately to conquer his fear, Maharaj had an epiphany: “It suddenly dawned on me that he had handed me a gift. The gift was there in that sharp point on my throat. All I had to do was dive on it, and I would be dead.”

Swanepoel, who was staring Maharaj intently in the eye, read his thoughts in a flash. “He panicked and withdrew the sword and walked out.”

As the meaning of this exchange began to settle, Maharaj understood that he had won. He and Swanepoel now both knew that it was Maharaj who held the trump in the bloody game they played: he could stop himself from talking by dying. Swanepoel stood back after that; he never again played a prominent role in Maharaj’s torture. And Maharaj would have it confirmed that Swanepoel had taken in precisely what had happened. “He told other detainees that he respected me.”

That is Maharaj’s recollection, at any rate. The story is worth telling in part because it is hard to know how reliable it may be. Nobody who has been tortured is a good witness to their ordeal. The experience as it happened is often untellable, for to a greater or lesser extent one has experienced a breakdown of self, a fragmented, disjointed experience hard to represent in narrative. To the extent that one places a coherent self in the story one tells, as Maharaj did, one is telling a heavily reconstructed story.

Maharaj depicts himself and Swanepoel as chess players, each at the top of his game. He goes so far as to imagine a perverse camaraderie between them; they walk away with a mutual respect for each other. Maharaj wants a rematch; he would like to show Swanepoel that he can better him at his own job. “My dream”, he writes, “was that one day I’d capture Swanepoel, and I believed I would be able to make him talk without physical torture.”

***

The Swanepoel Winnie remembered is unlike the one presented by Maharaj. She did not recall a tactical man aiming to outwit her. She remembered his raw hatred. And she described absorbing that hatred and making it her own. The significance of her memory of Swanepoel to her political career cannot be overstated. But it is only a partial guide to what happened between them.

Swanepoel was cruel to Winnie. When she fell ill as a result of her prolonged sleeplessness, her heart beating irregularly, her limbs swollen and blue, he not only persisted with the gruelling interrogation; he appeared to egg on her death. His aim, it seems, was to diminish her to the point of nothingness, to have her imagine herself as a corpse. The only useful thing she could leave behind, he and several of his colleagues suggested, was the information she might share before she expired.

This is what Winnie recalled five months after her interrogation. It is most instructive and revealing.

Swanepoel surely calculated that Winnie’s life was not actually in danger. Her death under interrogation would have been catastrophic for the government and a fate thus avoided. But her own fear that she was dying appears to have garnered his interest. His response was not just to pretend to egg on her death but to paint for her an image of her extinction.

This was a shrewd course of action. A lazier observer of Winnie would see a formidably strong person, full of confidence in her self worth and brave in the face of death. A deeper intelligence sees in the theatrical aspects of her conduct a mortifying fear of nonbeing. Getting Maharaj to imagine his own corpse was precisely the wrong thing to do, for it showed him a path to victory. Getting Winnie to imagine herself dead was probably right.

Swanepoel spoke to her, too, about her marriage. It was not surprising, he said, that Nelson had hardly spent a night at home since marrying her. His life was testimony to the lengths a man might go to escape a woman like her. Going underground, living for years like an outlaw, then getting himself locked in prison forever. Had he been Nelson, Winnie would remember Swanepoel saying, he would have done the same.

But a cruel face is not all Swanepoel showed her. There was a period during her interrogation, it seems, when he was beguiling. All she need do, he said, was make a statement over the radio to the black people of South Africa. There was every hope for improvement within the existing framework of law, she should tell them. They should abandon their illegal struggles. Whites and blacks ought to cooperate, she should say.

Swanepoel described in exquisite detail the future she would acquire in exchange. Nelson would be removed from B Section immediately and placed in a comfortable cottage. He would be allowed to read and write all he wanted and to receive unrestricted visits from his wife. Later, he would be released and settled in the Transkei, where Winnie, Zenani and Zindzi could join him and live a serene country life. Eventually, Nelson would be permitted to resume practising as an attorney.

There is no evidence that Winnie even considered this offer. Swanepoel probably never imagined that she would take it. He had in fact dangled a quite different bait, tailor-made to evade Winnie’s detection.

When her interrogation was over, Mendel Levin, the lawyer Maud had offered to Winnie’s co-defendants, and whom Moosa Dinath had come to Robben Island to persuade Nelson to hire, was permitted to see Winnie. Conspicuously, Joel Carlson’s requests to see her or any of his other clients were denied.

Winnie told Levin that she was ill, perhaps even dying. And Levin made a great show of demanding from the authorities that his client be examined by a doctor. The authorities, of course, immediately obliged.

Something else happened between Winnie and Mendel Levin. From her prison cell she wrote a letter to IDAF in London saying that Joel Carlson was not to be trusted and that money should be raised for Levin to represent the defendants. When Carlson asked her some time later why she had written the letter, she told him she had been sick and that Levin had helped her.

She had been caught in a trap. A familiar good-cop, bad-cop relay had been assembled with the twist that the good cop was disguised as her lawyer. It was an intelligent trap, for it was designed specifically for its victim. DM/ ML

Winnie and Nelson by Johnny Steinberg is published by Jonathan Ball Publishers (R360). Visit The Reading List for South African book news, daily – including excerpts!

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.