BOOK EXCERPT

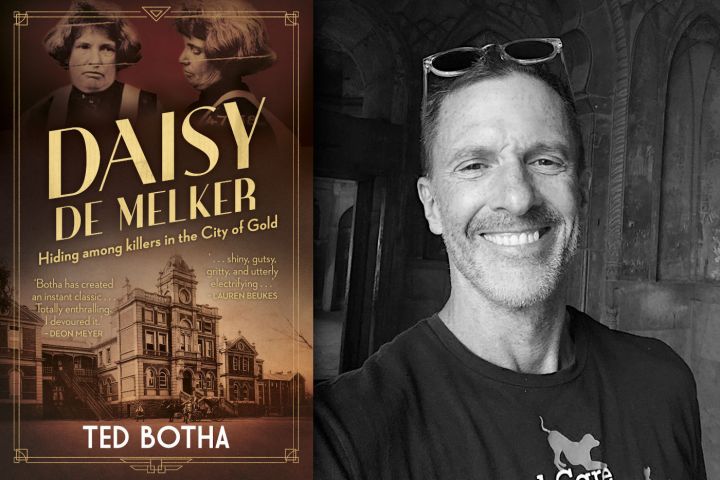

‘Daisy de Melker’ by Ted Botha is a true-crime classic

Newspapers in London, Shanghai and New York ran with the news – including a feature in Vanity Fair – and the streets rang out with ‘Daisy, Daisy, give me some arsenic do’. Ted Botha recounts the trial of Daisy de Melker.

Set in ragtime Johannesburg – a city of murder, mayhem and gold – Ted Botha’s new biography, Daisy de Melker, is set to become a true-crime classic.

Botha takes the reader into the underbelly of Joburg in the 1920s and 1930s – with the book showcasing some fascinating photographs from the time – as he traces the story of the mysterious woman hanged for poisoning her son, and suspected of poisoning two husbands for their life insurance money.

De Melker’s story unfolds in tandem with those of colourful Joburg characters like the Foster Gang and Herman Charles Bosman, and some cross paths with famous writers such as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Sarah Gertrude Millin.

De Melker went about her murderous business quietly and unnoticed – the most unlikely of killers. Even though people close to her kept dying, no one suspected a thing for 20 years.

When someone finally spoke up, it led to one of South Africa’s most sensational trials. Read an excerpt of the book here.

***

By September 1932, a month before the trial started, the public hostility towards Daisy was getting out of control. Nasty and macabre ditties could be heard on the street, many of them based on the popular song ‘Daisy Bell (Bicycle Built for Two)’: ‘Daisy, Daisy, give me some arsenic do / I’ve gone crazy to give all my dough to you. / You can then make another marriage / When I’m safe in the black carriage. / But soon you’ll flop – through a six-foot drop / Of a gallows that’s made for you.’

Even though songs and rhymes wouldn’t decide Daisy’s fate, [her lawyer] Harry Morris knew how important a role public opinion played in any trial. He only had to recall the murderer Dicky Mallalieu, whose good looks and reputation had counted for a lot in his acquittal. Mallalieu was handsome and dashing, and had gone on a wild and adventurous jaunt around the country. Meanwhile, his victim, Arthur Kimber, was an overweight taxi driver who dutifully paid his bills regularly and went to his job on time every day.

Unlike Mallalieu, Daisy had nothing on her side: She was unattractive, and the crimes she was accused of committing required a unique level of evil. Because of the ever-worsening public sentiment, Daisy had chosen not to have a jury but only a judge. Her fate lay in the hands of her lawyer, Harry Morris, and the man who would preside over the hearing, Justice Leopold Greenberg.

***

Despite the early hour, hundreds of people were already gathered on the lawn and steps outside the Supreme Court on the first day of what newspapers were calling ‘the poison trial’. Many had been there since the previous night, hoping to get a seat in the public gallery. On Pritchard and Von Brandis streets, spectators hung out of the windows waiting to get a view of the Black Maria when it arrived with the accused, Daisy de Melker.

Around the world – in London, Shanghai, New York – newspapers ran stories about the upcoming trial. In Vanity Fair Daisy was compared to the American murderer Winnie Ruth Judd, although the cases had nothing in common other than sensation.

One year earlier, Judd had killed two friends, Agnes Anne LeRoi and Hedvig Samuelson, and dismembered one of them, before transporting both bodies in a trunk and suitcases by train from Phoenix to Los Angeles. When she was apprehended at Central Station, it was because of the stench coming from her luggage.

Harry Morris arrived in court an hour before the hearing began, as was his custom. At the end of a long table stood Cyril Jarvis, his height suddenly accentuating the differences between him and Harry Morris.

The one was tall, handsome, a good dresser, thoughtful, a Rhodes scholar; the other short, bespectacled, pugnacious, slightly dishevelled, with no aspirations to being an intellectual.

But Jarvis wasn’t fooled. The chief prosecutor, like Harry’s other opponents, had repeatedly seen him cast a spell over witnesses, jurymen, the public gallery, even the judge, until, imperceptibly, the mood in court changed, and a watertight case sprang a leak, and someone who had obviously been guilty, even of murder, was suddenly discharged with a slap on the wrist.

Jarvis had also received some especially worrying news. William Sproat, one of his key witnesses – the reason they were here today, the man who had started the whole investigation against Daisy – was seriously ill with double pneumonia, and it was unlikely that he would be able to testify.

Behind Jarvis the public gallery was already packed, while another 200 people waited in the vestibule outside for a chance to get in, ‘mostly with fashionably dressed women’. Next to the jury box stood a sergeant of the court, making sure that it stayed empty, except for special guests.

At one point, two well-dressed women in their early forties came through a side entrance. Both of them motioned a greeting to Harry Morris and Jarvis, and took their seats in the jury box as spectators, the only way a woman would be allowed into it. They were the judge’s wife, Jenny Greenberg, and her friend Sarah Gertrude Millin.

Daisy was ushered in, dressed in a black suit with a lace front – the outfit she had worn for the funeral of [her son] Rhodes – and a beret, which she took off. She was holding a notebook in front of her, a prop that would be with her every day of the trial. At her back, as she sat on a stool in the teak dock, stood a policeman and, nearby, a wardress.

The moment Justice Leopold Greenberg entered, everyone rose.

The youngest judge ever appointed to the Supreme Court, at the age of 39, Greenberg was known for his even-handed decisions and his sharp wit. Because there was no jury, he had opted to choose two assistants – AA Stanford and JM Graham, both senior magistrates with considerable experience – whom he could consult and who themselves could also ask questions of the witnesses. It suddenly struck Issie Maisels that Daisy’s fate was in the hands of three Jews: himself, Morris and Greenberg.

Each time Daisy was asked to plead, and with an almost resolute tone, her response was the same: ‘Not guilty.’

Jarvis, in his opening address, said that the Crown would call 59 witnesses. He would show that Alfred Cowle and Robert Sproat [her first and second husbands, respectively] had died of strychnine poisoning, the motive being the money that Daisy would inherit under their wills. She had given arsenic to Rhodes Cowle because relations with him had not been good since her marriage to Sidney de Melker. There were regular quarrels, and Rhodes had become impossible.

Jarvis began by describing Daisy’s background – a roaming life that took her to Rhodesia, Cape Town, Durban and, finally, Johannesburg – and the sudden deaths that went wherever she did: first her fiancé Bert Fuller and then her four children. Daisy, masked behind a pair of large owl-like spectacles, had opened the notebook in her lap and began writing in it almost from the moment the first witness was called.

***

They came through quickly at first – the undertaker, the municipal pension agent, an insurance man – before the first mention of poison was made.

A pharmacist from Rhodesia, who had known Daisy as a child, explained how easy it had been to get strychnine there until only the previous year, 1931. Daisy’s eldest brother, John, who had come down for the trial, said that when she came to live with him from the age of ten, in 1896, he had bought strychnine that was ‘whiteish’ in colour when he went out hunting, which he used to destroy wolves, but he had kept it ‘under lock and key’ and then destroyed it afterwards. Jarvis asked him a question about Daisy’s engagement to Bert Fuller, and Judge Greenberg interrupted.

‘There is no charge of [her] murdering Fuller,’ he reminded the prosecutor, who nodded.

‘It is evidence of accessibility to poison,’ Jarvis explained.

‘Is it the suggestion of the Crown,’ Greenberg put it to him, ‘that she had this strychnine in the early part of the century and kept it till 1923?’

‘It is possible.’

Two of Daisy’s sisters, Fanny McLachlan and Gertrude Puzey, were called next. Even though neither had seen the accused much over the years, they said she seemed to have a normal marriage, especially to Cowle, and was affectionate towards her son.

From the evidence table, Jarvis retrieved several letters that the accused had written to McLachlan, and read extracts showing Rhodes’s reason for conflict: ‘His ambition seems to be to see how nasty he can be towards me … His one object in life seems to be to have a two-seater car.’

Morris got McLachlan to admit they were not only a happy couple but a very happy one, and that Daisy had grieved bitterly after Cowle’s death. She believed Daisy gave in to her son too easily.

‘Did your son Ginger make any report about Rhodes’s conduct while he was staying with the De Melkers?’

Her son had told her of various incidents, such as Rhodes swallowing poisonous liniment to upset Daisy. DM/ML

Daisy de Melker by Ted Botha is published by Jonathan Ball Publishers (R290). Visit The Reading List for South African book news, daily – including excerpts!

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.