BOOK REVIEW

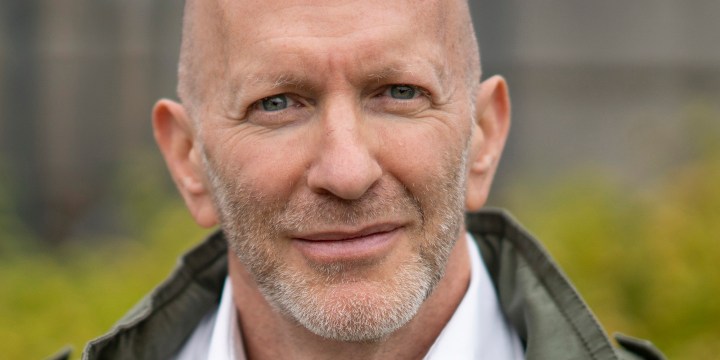

Historian Simon Sebag Montefiore offers a fresh perspective on the biggest story ever told

Montefiore’s new book, “The World: A Family History”, focuses on the family as the lens for examining our human story. It is intensely readable and all along the journey he offers excellent rest stops and fascinating diversions.

Speaking with British historian Simon Sebag Montefiore, let alone trying to make a serious dent in his vast written output by some sustained reading before our meeting, is a daunting task. It is clear that in carrying out his research for this, his newest book, the author seems to have read nearly everything concerning human history in order to guide him in writing his own grand overview of the entirety of the human experience.

Before this newest volume, The World: A Family History, he had written a long list of immensely readable, yet deeply scholarly volumes on Russian history that examined some of Russia’s most important historical figures, including one on three centuries of Romanov czars, a separate volume on the empress Catherine the Great and her military leader Grigory Potemkin, and two volumes on the life of Joseph Stalin.

One of those two books on the Soviet leader — Young Stalin — sought to explore the inner life of the dictator and the origins of his character and thus the shape of his later behaviour, through an exploration of the tyrant’s early — and too often overlooked — formative years, including his time as a small-time gangster. That period would be crucial in shaping his ideas about power and his views about the world around him.

But beyond writing about Russian history, there have been carefully edited collections of historically important letters and speeches, as well as an engrossing history of the city of Jerusalem. This latter work begins with the city’s prehistory and moves on through how the three Abrahamic religions have interpreted their relationship to that city — physically, religiously and politically. Montefiore’s writing also includes several novels.

All of Montefiore’s books are stylish and readable, rather than phrased in the “academese” that can repel many readers. Even the digressions from his main narratives are illuminating and informative. Nevertheless, as a conscientious historian, in his writings on Russian history, Montefiore has drawn upon a vast library of earlier scholarly works and secondary histories on his topic, together with firsthand research in the Kremlin archives and other Russian sources.

In our conversation, he described the astonishing circumstance in which Kremlin archivists had been ordered by Vladimir Putin (apparently based on that ruler’s positive responses to some of Montefiore’s previous work) to assist him in working through the voluminous records held by them from Stalin’s years. This resulted in a cadre of Kremlin archivists working with Montefiore to decipher whether a marginal note had come from one of Stalin’s henchmen such as Beria, Molotov, and Malenkov — or from Stalin himself — depending on the content, the style of the handwriting, or even the colour of the ink.

Given Montefiore’s reputation, his output and his readable style, it should not be a surprise his books have been translated into dozens of languages and have been bestsellers globally.

A vast tableau

The World: A Family History, is no exception in the readability sweepstakes. The text is a vast tableau that features hundreds of rulers (mostly male) and the millions of the ruled (and the rulers’ vanquished victims) throughout the world; crowds of barbaric, learned, wily or despicable aides, religious leaders, outcasts, rivals, powerful eunuchs, scoundrels and saints; and yet more crowds of wives, concubines, and lovers (male and female both) — together populating some 1,300 pages.

This author recently met with Montefiore while he was in South Africa on a book tour for his new book. (A full podcast of the interview in the weekly programme, The Deep Dive, is available here.)

It is well worth it for a reader to invest the time and effort to conquer this volume, even though it will take more than a few days of concentrated reading. As one reads about Alexander the Great’s conquests, his family, and his generals and their heirs, for example, one is tempted to skip ahead, stopping at yet another consequential moment in history, or at places and people of special interest to the reader.

It is possible (even likely) a reader will end up reading parts of it out of sequence, just for the pleasure of savouring the individual chapters. For Northern Hemisphere readers, the book will be a superb summer vacation companion — or, looking further ahead, it could be an excellent holiday gift to anyone with a love of history.

Montefiore also brings a particular, personal element to global history. In our discussion, he explains the book actually had its origins in an authorial response to the dislocations of the global shutdowns that came about in response to the multiyear Covid pandemic. The rest of us should have been as productive as Montefiore was with his volume in response to the restrictions and dislocations of the pandemic!

In crafting this volume, it becomes clear he is no fervent adherent of any one overarching theory of history or thesis about the rise and decline of nations, peoples, and civilisations. Just as he has declined to embrace, wholeheartedly, the teleological idea of the inevitability of human progress or its opposite of ever-repeating cycles (the Christian versus the ancient Greek view of the nature of human history), he has also eschewed placing all his chips on the Marxist explanation of those economic gears of history grinding away towards achieving history’s inevitable outcome.

Bypassing the unresolvable conundrum

Similarly, he has not fallen strictly in line with an older, more traditional style of history writing — the one that builds a historical narrative around the deeds (and flaws, foibles or overweening hubris) of a great man or woman as the primary mechanism by which history moves on. He thus bypasses the unresolvable conundrum that asks: Do grave crises call forth great men or women, or do great men or women create those grave crises in the first place?

Moreover, although they have important roles in his tapestry of history, for Montefiore, as he tells it through his narrative, the views that demography (such as the size or distribution of a population), or geography (the relative proximity of a civilisation to rivers, harbours or trade routes, or constrained and shaped by mountains, deserts and seas) are inevitable as a nation’s destiny are similarly somewhat misplaced. Still, his discussions about the interconnections between the global production of sugar cast a harsh light on the growth of transatlantic slavery and European exploration and state-on-state competition and warfare.

Also, he does not give absolute pride of first place to technological developments such as one might find in historian Lynn White’s view of the revolutionary impacts of saddles and stirrups, or effective hydropower, the reciprocal steam engine, or electricity as fundamental motive forces for progress (or social disaster). Montefiore does, however, give serious attention to the effect on warfare (and thus history) of the development of gunpowder and its uses for combat. While all these factors have their roles and important influences, they interact in powerful, sometimes unexpected ways for Montefiore. For the historian, however, it is people, and especially families through generations, that become a crucial engine for history’s developments.

As Montefiore writes, “There have been many histories of the world, but this one adopts a new approach, using the stories of families across time to provide a different, fresh perspective. It is one that appeals to me because it offers a way of connecting great events with individual human drama, from the first hominins to today, from the sharpened stone to the iPhone and the drone. World history is an elixir for troubled times: its advantage is that it offers a sense of perspective; its drawback is that it involves too much distance. World history often has themes, not people; biography has people, not themes.”

In common with his embrace of human history as the complex, interwoven and sometimes unexpected, parallel stories of developments across the globe, the author has incorporated all of those above elements as contributing factors in his global history. But it is his innovative approach to peg his story on the idea of families — although not in the more jejune sense of “We are family” as in the words of a popular song — that will be especially attractive for readers.

It is the idea that a wide array of families, often ruling families, but sometimes religious leaders and others, are a key element of the human story. This is true whether it’s in the descriptions of the interactions of the rulers of African kingdoms with the Mediterranean world (as gold, salt and slave trading nations) over millennia; yet other networks of slave traders stretching from the Slavic states in what is now Russia on to all the states surrounding the Mediterranean basin; the Meso-American and Incan empires’ interactions and connections with the families of the early Spanish conquistadors; or the vast, extended tendrils of the families of Mongol and Turkic tribal leaders across the centuries and throughout Asia.

Then there are the roles of the more familiar families like the Krupps, the Morgans, the Borgias and the Medicis — as well as so many other lesser-known lineages that have all played big roles throughout the tides of history. These discussions apply to China, South Asia, Japan and the rest of the globe as well.

Tapestries of interconnections

Montefiore’s examinations of these tapestries of interconnections across time and space have also been influenced by his own family’s history. On his father’s side, it stretches back to Jewish life amidst the civilisation of Moorish Iberia. With the expulsion of the Jews from Spain and Portugal at the end of the 15th century, the family moved on to Livorno in Renaissance Italy, and then, eventually, settled in England, once Jewish life had been allowed to return to that country in the 17th century (after the expulsion of the 13th century). As the Montefiore family became established in England, one of the writer’s ancestors was the financier, government adviser and writer Moses Montefiore.

As a further note on this family journey, as he explained it, the author’s very name functions as a kind of recapitulation of that history. “Sebag” is derived from the Arabic and “Montefiore” is an Italian surname adopted during the years on that peninsula. In passing, it is also interesting that a second contemporary British historian, Simon Schama, also bears the same first name. The two men are sometimes popularly linked as “the two Simons” — especially since they are both at the apex of popular yet scholarly history writing.

Things that may startle some readers with delicate sensibilities are the writer’s rather detailed descriptions of all the torture, maiming and mass killing carried out from the time of ancient Assyrian hegemony in the Near East on through to the present. And there are also Montefiore’s depictions of the physical mutilations and sacrifices of prisoners and other chosen victims, either in the exercise of religion or in efforts to suppress revolts, for the reader to contend with. But such things are history and it is pointless to avoid contemplating them for any clues to a better future.

Montefiore’s book also offers extended discussions on the nature of sexual politics as an integral part of the efforts by those in power to rule. These have included acts by religious and secular figures (and those whose positions fused both spheres) — such as all those carefully negotiated marriages, the routine exercise of concubinage and polygamy, the calculated intermarriages between and within ruling families (without the benefit of modern genetic knowledge about the physiological dangers), as well as the exercise of homosexuality. There are also discussions of those rather rarer occurrences where women made use of these networks to exercise real power by virtue of their exceptional skills and thinking as leaders, as well as their capabilities of manipulating palace intrigues to hold power — often from “behind the curtain”).

There are also frequent discussions of how so many rulers became addicted to opium, alcohol or other drugs, and medically administered poisons, and how such weaknesses affected their abilities — or even the survival of their families and their polities. Such discourses by the author are clearly not extraneous to his larger discussions about the exercise of power. They can, in fact, be close to central in searching for an understanding of that will to power, because almost no matter where one looks, these personal failures essentially come about because rulers could carry them out without much restraint. Too often there have been few guardrails to prevent such miscarriages. For thousands of years, such behaviours and decisions were central to the exercise of political leadership and must be addressed seriously by historians, rather than largely ignored to protect the tender sensibilities of some readers.

Reflections on three histories

Accordingly, as a reader, one pours over the vast canvas of Montefiore’s knowledge and his skills as a storyteller. In reading this volume, the reviewer’s mind went back to three histories that were enormously influential with readers throughout the 20th century — and especially to younger or non-specialists.

First, there was British novelist HG Wells’ The Outline of History, initially published just after World War 1, and eventually revised to take into account World War 2. Wells’ book attempted to portray human history as a kind of struggle between the antagonistic poles of greater social progress and liberty versus the aims of world domination by one nation or one ethnicity.

For Wells, for example, Napoleon served as a kind of antihero with universal aspirations, but one who simultaneously was fatally tempted by what we might now call the dark side. By contrast, despite its failures, the League of Nations represented an effort to achieve the best chances for humankind, following the carnage of World War 1.

A second volume was the Dutch-American historian Hendrik van Loon’s The Story of Mankind. Written especially for younger readers, Van Loon selected what and what not to include by subjecting all materials to the question, as he put it: “Did the person or event in question perform an act without which the entire history of civilization would have been different?” This book, too, is still widely read and was even turned into a film.

However, critics of Van Loon’s work note it is considerably biased towards Western and Western European developments, rather than achieving the promise of the title.

Then, too, there has been the 11-volume series by Will and Ariel Durant, The Story of Civilization. Beyond bookstore sales, the full set was offered by some subscription book clubs as a kind of clickbait to entice individuals to subscribe to those book clubs throughout much of the 20th century. Will Durant had said of this giant work that it was, “To tell as much as I can, in as little space as I can, of the contribution that genius and labour have made to the cultural heritage of mankind.”

For his part, Montefiore explains that his new book addresses the reality that “the harshness of humanity has been constantly rescued by our capacity to create and love: the family is the centre of both. Our limitless ability to destroy is matched only by our ingenious ability to recover.

“In this book, I have written of the fall of noble cities, the vanishing of kingdoms, the rise and fall of dynasties, cruelty upon cruelty, folly upon folly, eruptions, massacres, famines, pandemics and pollutions, yet again and again in these pages the high spirits and elevated thoughts, the capacity for joy and kindness, the variety and eccentricity of humanity, the faces of love and the devotion of family-run through it all, and remind me why I started to write.”

For those interested in exploring the wide-ranging roster of works (many familiar and popular works as well as many more from specialists) Montefiore consulted in the process of writing The World: A Family History, rather than appending them at the back of the actual book, in an author’s note he tells readers to go here.

One modest criticism of this book, however, must be the absence of maps, genealogical charts, illustrations, or timelines to help the reader keep track of all the events and people that populate this book. Perhaps these can be added to electronic versions of the book in future. DM

Simon Sebag Montefiore’s The World: A Family History, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, ISBN 978 0 2978 6967 2 (hardback), ISBN 978 0 2978 6969 6 (ebook), and ISBN 978 1 4091 8048 7 (audiobook). Paperback to come.

Comments - Please login in order to comment.