SPOTLIGHT IN-DEPTH

New screening programme planned for cystic fibrosis in South Africa

In recent weeks, cystic fibrosis has been in the headlines because of a court case about access to new treatments for the genetic condition. After reporting on the case, Catherine Tomlinson now unpacks how CF is diagnosed in South Africa and why so many cases fall through the cracks. The good news, she reports, is that efforts are under way to establish a national infant screening programme.

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is one of the most common genetic disorders inherited from parents, but actual cases of the disease in South Africa are rare.

There are fewer than 600 people who have been diagnosed with CF in the country – experts believe this is only a fraction of the actual number of people with the condition. Most babies born with CF, it is believed, are never diagnosed and die in infancy due to CF-related complications and infections. A new screening programme may, however, help change this.

Who can get cystic fibrosis?

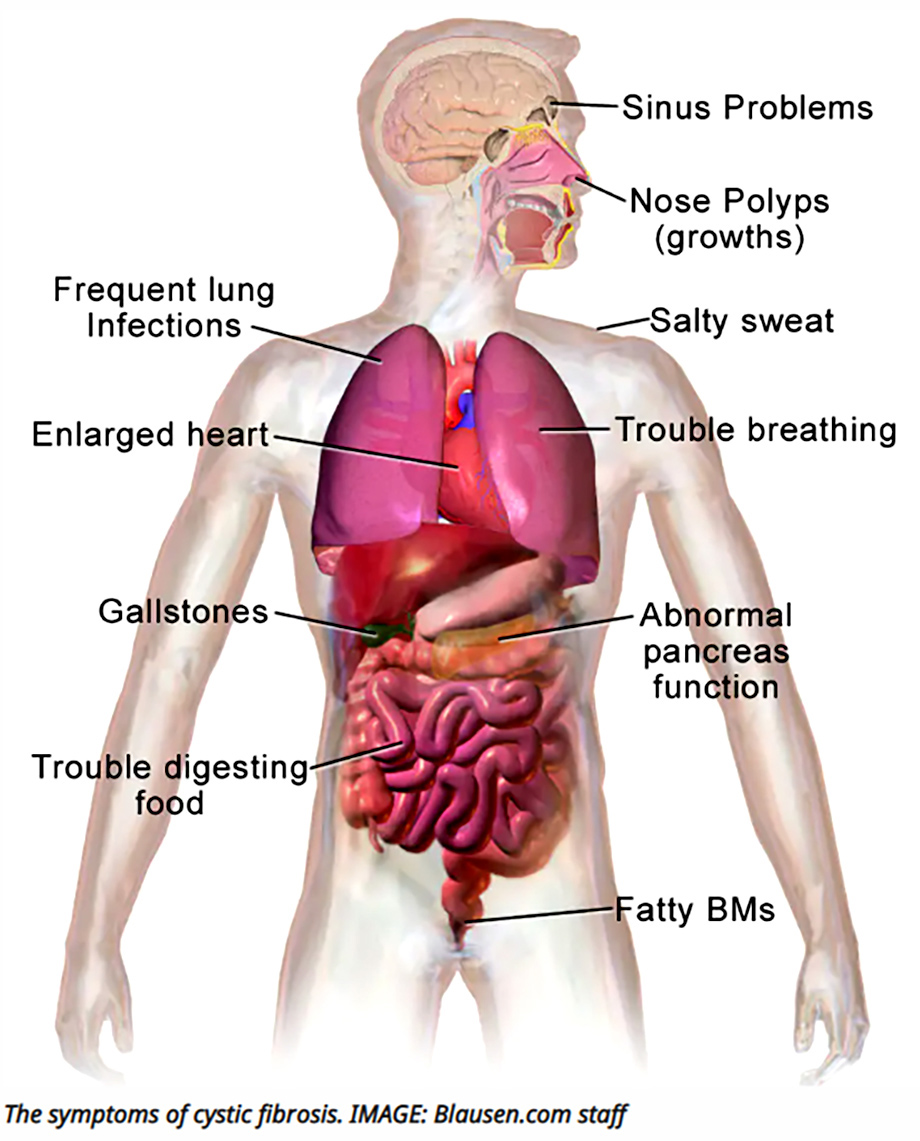

While CF is more common in people with European ancestry, it can affect people of any ethnic background. Lingering misbeliefs in developed countries that cystic fibrosis is a “white disease” and Eurocentric testing tools have led to underdiagnosis in other ethnic groups – including in people with African ancestry living in the developed world.

In South Africa it has long been known among CF specialists that the illness is not limited to the white population. The first diagnosis of CF in a black child in South Africa was made in 1959. Yet, an ongoing lack of awareness about CF among healthcare workers in the country, the absence of a newborn screening programme, geographical barriers to diagnostic services, and the similarities of CF’s presentation in infants with more common conditions – such as TB, HIV and poverty-related malnutrition – means that most babies born with CF in South Africa might never be diagnosed before they succumb in infancy to malnutrition-related complications caused by untreated CF.

Cystic fibrosis is one of the most common genetic disorders inherited from parents, but actual cases of the disease in South Africa are rare. (Photo: iStock)

Extrapolating from available genetic and population data, Professor Marco Zampoli, a paediatric pulmonologist from the University of Cape Town, estimates that between 2,000 and 3,000 babies may have been born with CF in South Africa since 1999 – including more than 1,000 black African babies. Yet, based on data from the national CF registry, which to date has recorded 53 black Africans with CF (10% of all cases), very few of these babies were ever diagnosed with CF and linked to appropriate care. And when diagnosis does occur, it often occurs late after CF has already done irreparable harm to the body and health.

What is the national cystic fibrosis registry and why is it important?

South Africa’s national cystic fibrosis registry was established in 2018. It includes demographic and health data for all people diagnosed with cystic fibrosis in South Africa who consent to be included in the registry (only one known patient has not consented to date).

Registries of people living with CF have long been used in developed countries. They allow for monitoring of CF outcomes across the country and the comparison of outcomes across different demographic groups and treatment centres. Registries can be used to identify where there are positive health outcomes and successes, as well as challenges and gaps. And, when a pharmaceutical company seeks to undertake a CF-related clinical trial, registries enable clinicians and researchers to identify eligible patients who may be interested in participating.

While the South African government does not currently offer universal newborn screening for cystic fibrosis and other genetic and metabolic conditions, it is moving in this direction. (Photo: Halden Krog / Spotlight)

Vertex has secured a global monopoly over CFTR modulator therapies by aggressively pursuing patents related to the class of drugs around the world. (Photo: TAC Archive / Spotlight)

Since the establishment of South Africa’s registry in 2018, two annual reports have been published compiling and explaining the data collected in the registry. The most recent, published in 2020, provides data on 525 people diagnosed with CF in the country who are receiving care in public or private facilities.

According to the registry, more than half of CF patients in the country are under the age of 18, and 16% are of preschool age. Among patients diagnosed with CF in South Africa, 69% identified as white, 19% as mixed race, 10% as black and 1% as Indian.

How is cystic fibrosis diagnosed in South Africa?

Consensus guidelines for the management of CF were published by the South African Cystic Fibrosis Association (SACFA) and the CF Medical and Scientific Advisory Committee (formed under SACFA) in 2017. These outline the steps for diagnosing CF using a combination of different tools – sweat tests, genetic tests and faecal pancreatic elastase tests (which test stool to determine whether the pancreas is functioning properly).

Most babies born with cystic fibrosis in South Africa might never be diagnosed before they succumb in infancy to malnutrition-related complications caused by untreated CF. (Photo: WC DOH / Spotlight)

Without a newborn screening programme for CF, most people with the condition are only diagnosed after showing clinical symptoms. In newborns, symptoms may include intestinal obstructions, failure to thrive, malnutrition and recurrent infections. In older children, symptoms often include a chronic cough, wheezing and recurrent infections requiring a hospital admission. Early diagnosis is key to slowing the progression of the disease and ensuring that patients can access therapies to manage CF’s potentially fatal symptoms.

Read more in Daily Maverick: What happens to people in South Africa who have rare diseases?

Zampoli explains that the sweat test is typically the first one offered to patients suspected of having CF. CF impedes the normal movement of salt and water across cell membranes throughout the body, including sweat glands, and one of its hallmark symptoms is salty sweat. According to Zampoli, the sweat test “is a small instrument… it has two probes which are attached to the forearm… which stimulate small electric currents to stimulate the sweat glands to produce sweat.” Then, “there’s a little device which collects a small sample of the sweat and that is sent to the laboratory to measure [its] salt content. High salt content in sweat (chloride > 60 mmol/L) is diagnostic of CF.”

It is important for people with cystic fibrosis to know what genes they have, since these are a good predictor of the severity of the disease they will have. (Photo: Denvor de Wee / Spotlight)

Zampoli, however, cautions that conducting sweat tests requires a high level of technical skill and experience and that these skills only exist at tertiary hospitals in city centres in the public sector and private-sector laboratories that are also largely limited to city centres.

“In rural areas and in the Eastern Cape, Northern Cape, Limpopo and Mpumalanga, there are no facilities to do sweat tests. So, if a doctor suspects CF, they must refer patients to a lab in one of the major centres,” says Zampoli. Patients who receive two positive sweat-test results should have their cystic fibrosis confirmed through genetic testing.

Why is genetic testing important for people with cystic fibrosis?

A startlingly high number of people carry the genetic coding for cystic fibrosis in their DNA. In South Africa, according to the consensus guidelines, it is estimated that one in 27 people from “Caucasian” ancestry, one in 55 people from mixed-race ancestry, and one in 90 people from black African ancestry carry the cystic fibrosis gene. While carriers of the gene are not affected by CF diseases, when two carriers have a baby together, then their baby has a one in four chance of having cystic fibrosis. The baby must inherit two copies of the CF gene, one from each parent, to be affected by CF.

According to Zampoli, it is important for people with CF to know what genes they have, since these are a good predictor of the severity of the disease they will have. CF disease has a broad spectrum in how it can present. In fairly mild cases in men, its only symptom may be infertility. Yet, in severe cases, it is debilitating and life-shortening. There are more than 2,000 different cystic fibrosis-causing gene mutations and different mutations have different prevalence levels across different racial groups.

Zampoli says that knowing what CF-causing genes you have is essential to determining eligibility for new highly effective CF medicines, known as CFTR modulator therapies. While these medicines are not yet available in South Africa, cystic fibrosis patients are taking legal action to address this (Spotlight reported on those efforts here).

How is genetic testing performed?

According to CF guidelines used in South Africa, patients who receive two positive sweat-test results should be referred for genetic screening – to confirm their CF diagnosis and to identify what genes they have. The usual genetic test performed in South Africa is a commercial screening test kit that can detect the presence of up to 50 known CF-causing genes.

However, Zampoli explains, commercial tests were designed to suit the needs of European populations and while they can identify the genes carried by most people with cystic fibrosis of Caucasian descent, they can only identify the CF-causing genes in about 60% of black Africans with CF.

Patients whose gene mutations cannot be identified using existing commercial screening kits require full sequencing of their CF-causing genes. Full sequencing allows for detection of any CF-causing genes, including uncommon and unknown genes. Unknown genes are those whose reporting may be new and whose clinical significance is not yet known.

While full sequencing is not available in the public sector, CF clinicians are often able to find ways to have it done when needed – including using research funds – as the costs of this type of sequencing are coming down, says Zampoli. He adds that full gene sequencing must be done if routine commercial kit testing does not identify two CF genes when CF is suspected in someone based on symptoms and abnormal sweat-test results.

How can CF detection be improved in South Africa?

While universal newborn screening is not available in South Africa, it is broadly used in most developed countries to screen for genetic and metabolic diseases. Professor Chris Vorster, director of the Centre for Human Metabolomics and clinical pathologist at North-West University, explains that newborn screening efforts should target “those conditions that by the time the clinician makes the diagnosis, then typically the damage done is already irreversible”.

Vorster’s lab has developed the capacity to undertake newborn screening for a range of genetic and metabolic conditions which, in the absence of government funds for a national screening programme, it now offers through a fee-for-service model together with a company called NextBiosciences, located in Midrand, Gauteng.

NextBiosciences’ currently available newborn screening test screens for multiple genetic and metabolic conditions, including those for which dietary interventions early in life can prevent serious mental disabilities.

Their newborn screening test, which includes CF screening, is available to private patients at R1,646.16 (excluding collection, courier and administration costs). It is not typically covered by medical aid schemes.

While the South African government does not currently offer universal newborn screening for CF and other genetic and metabolic conditions, it is moving in this direction. In November 2021, the Department of Health published “Clinical Guidelines for Genetics Services”. These recommend “newborn screening for congenital disorders where newborn screening prevents significant and irreversible morbidity and/or mortality” and adds that “more studies are needed to determine which congenital disorders must be included in the programme”. “However, an initial screening programme should at [a] minimum include congenital hypothyroidism, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, cystic fibrosis, classical galactosemia, glutaric aciduria type 1, and propionic acidemia.”

Life-changing new treatments that dramatically improve the prognosis for people with the disease have been developed, but they are expensive, and Vertex, the US company making the drugs, has decided against registering them in South Africa. (Photo: Chemist 4 U / Flickr / Spotlight)

Vorster notes that further research is needed to inform the roll-out of universal screening in South Africa, including gaining an understanding of the earliest points at which newborn screening can be performed. He also notes that in South Africa’s public sector, most women leave the hospital six hours after giving birth.

In response to a question from Spotlight regarding the Department of Health’s timeline for introducing newborn screening (including CF screening) in South Africa, spokesperson Foster Mohale says: “The department continues to commit to implement[ing] the newborn screening in South Africa. There are processes between the approval of the guideline and actual implementation of the guidelines. Such processes include preparing the service delivery platform to adapt to the new guidelines. The approval of the guideline came during the Covid-19 pandemic, which delayed the triggering of guidelines implementation.”

Mohale says it is envisaged that an implementation study on the feasibility of a roll-out of the programme will be completed in the 2023/24 financial year. Depending on the results of that study, the country roll-out plan would then be developed.

How is newborn screening for CF done in South Africa?

Recent research published in the US has demonstrated that newborn screening tools, like other CF diagnostic tools, are Eurocentric and have lower success rates in identifying CF in black and Hispanic Americans, since they test for CF-causing genes more common in the European population.

Vorster notes that the approach currently used in South Africa for newborn screening by NextBiosciences and North-West University avoids this pitfall since rather than screening for CF-causing genes in newborns, the screening offered involves “immuno-reactive trypsinogen screening” – which looks at whether a chemical made by the pancreas is abnormally high. Vorster says that unlike in the developed world, genetic screening only occurs at a later stage in South Africa after an initial positive CF diagnosis is made through a sweat test or a faecal pancreatic elastase test.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Landmark SA court case takes on US maker of cystic fibrosis drugs

Zampoli says that while access to new transformative medicines for CF remains critical to improving CF patients’ outcomes, early diagnosis can also save lives and prevent the progression of CF by allowing patients to begin currently available therapies needed to treat symptoms and prevent the progression of the disease. But he adds that there are large geographical barriers for many people born outside of city centres to accessing required specialised CF care.

Either way, critically important as it is, diagnosis is always only a first step. Kelly du Plessis, founder of Rare Diseases South Africa, says: “If we’re going to start the newborn screening process… where you are actually identifying cystic patients early, you also have to have the interventions in place to help them once they’ve been identified.”

Whether those interventions are indeed in place will be the subject of the next article in this Spotlight special series on CF. DM/MC

This article was published by Spotlight – health journalism in the public interest.

Comments - Please login in order to comment.