BOOK REVIEW

Charlayne Hunter-Gault’s message of hope from the US and South Africa is a must-read

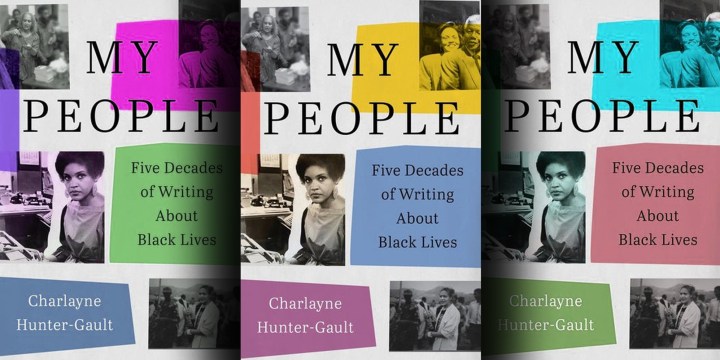

In her new book, My People: Five Decades of Writing About Black Lives, award-winning American journalist and social commentator Charlayne Hunter-Gault reminds us we are all one people. Racism, however potent and profitable, is a social invention. My People is published by HarperCollins.

Charlayne Hunter-Gault’s My People: Five Decades of Writing About Black Lives celebrates a lifetime of hard-won progress in race relations. She is not naïve and doesn’t hide harsh realities. But this carefully curated collection of 60 articles and televised interview transcripts conveys hope.

From a foreword by a much younger black female journalist, Nikole Hannah-Jones, who led the Pulitzer Prize-winning 1619 Project, to an epilogue’s transcript of her 2020 interview with conservative columnist David Brooks about the role of community leadership, one cannot avoid comparisons with South Africa, where Ms Hunter-Gault resided for 17 years.

The book has six parts which are thematic, interrelated and cumulative:

- Toward Justice and Equality: Then and Now;

- My Sisters;

- Community and Culture;

- A Single Garment of Destiny;

- The Road Less Traveled; and

- Honoring the Ancestors.

In 1961, Charlayne Hunter and Hamilton Holmes became the first black students to integrate the University of Georgia, founded in 1785. Holmes eventually became a medical doctor, Hunter a journalist, opening the door to Hannah-Jones, among many other black journalists.

Hannah-Jones ends her foreword thus: “Ms Hunter-Gault shows us, as long as the architecture of racial inequality remains, so does the journalists’ mandate to investigate and report on it.”

Following precedent-setting and award-winning stints at the New York Times, the New Yorker magazine, and US Public Broadcasting Service’s (PBS’s) Nightly News Hour, Hunter-Gault moved to South Africa in 1997, first, as American Public Broadcasting’s Africa correspondent and from 1999 as South Africa’s Bureau Chief for CNN. Her dozen or more articles about the freedom struggles and legacies of white racism add an important dimension.

The book’s first three parts provide fresh insights into America’s struggle for civil rights that should interest African and other foreign audiences as well.

Part I recounts the slow non-linear but discernible progress in achieving racial justice since the 1960s. It features Georgia that recently elected its first black US Senator, despite ongoing efforts at voter suppression.

She focuses, however, on local community leaders, whether in Atlanta, the rural South or Harlem in urban New York, and initiatives to benefit educational opportunities for black youngsters, help enroll more voters, fight crime, or fight racism in schools and local communities. With 14 articles Part I sets the tone for the volume.

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

Part II — My Sisters — contains 11 articles to showcase the role of women who successfully confronted the dual curse of racism and sexism both in the US and South Africa. She features black female politicians, MDs, social workers, civil rights leaders, and a South African woman judge. In a personal introduction, she recalls that: “From my earliest years, Black women helped me on my journey into journalism.”

Part III — Community and Culture — complements and extends the previous articles on community-level actions and norms to counter racial exclusion and discrimination.

Part IV has articles she wrote from and about Africa. She gave the section the title A Single Garment of Destiny, a term borrowed from Dr Martin Luther King. She draws parallels between freedom struggles in the US and South Africa. Readers of her 2006 book, New News Out of Africa, will find her views here familiar. Specific articles about freedom in Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Tunisia are of fresh interest.

Parts V and VI contain articles that recall the first part’s note of hope about the struggle for justice and equality. Part V recollects her early days in segregated Georgia, and the perils of being at the vanguard of integration at the University of Georgia. My favourite article in Part V is How the AME Church Helped Build My Armor of Values.

She begins Part VI, Honoring the Ancestors, by crediting South Africans with teaching her a positive way to deal with mortality. South Africans rarely say “death” but instead speak of passing or transitioning to be among one’s ancestors. And as she notes, when the ancestor is being remembered you end with the phrase, “Long live!”

This is not just comforting but a profoundly important reminder of our common heritage. As the eminent South African palaeontologist Phillip Tobias once told me: “Whenever a visitor asks, ‘What has Africa ever contributed to civilisation?’ I reply, how about human beings?”

By referring to our common ancestry, Hunter-Gault reminds us we are all one people. Racism, however potent and profitable, is a social invention. Geneticists confirm race to be a minor physical variant.

In the book’s last two articles, Hunter-Gault pays tribute to two black men who dedicated their lives to non-racialism and democracy’s universal principles. One, When I Met Dr King, emphases his humility and the enduring effects of his inspiration.

Nelson Mandela, the Father is the book’s final article. It captures the essence of the man, his “stubborn sense of fairness”, patient humility, and enduring inspiration to all of us. For this ancestor “Long Live!” is less a shout than our common prayer.

For the Epilogue, Reasons for Hope amid America’s Racial Unrest, the author provides a transcript of her 2020 PBS NewsHour interview with David Brooks, a New York Times columnist.

Brooks had visited local communities across America, many poor, black and from disadvantaged backgrounds. In 2019, as a counterpoint to America’s many divisions, he wrote a series of columns about “weavers”, individuals able to weave together diverse individuals and local groups for collective betterment. When neighbours help neighbours, communities become stronger, word spreads, and communities recover their resilience.

The Epilogue affirms Hunter-Gault’s belief that overcoming hardships and setting a good moral example in ways that benefit others builds hope, even among those most disadvantaged.

It is a much-needed message of a must-read book. DM

Comments - Please login in order to comment.