EXCAVATING THE PAST

The trail of red rust that leads to the beginning of human culture

Up on the Bomvu Ridge, high up in the hills north of the Eswatini capital of Mbabane, the re-excavation of Lion Cavern — possibly the oldest mine in the world — is lending further evidence to southern Africa’s position as not only the cradle of humankind, but also of human culture.

‘It’s not a cave, it’s a mine and totally artificial. They mined ochre, a form of oxidised iron. Basically, it is red rust, technically known as haematite,” says Bob Forrester, a heritage consultant for the Eswatini National Trust Commission, working with Dr Gregor Donatus Bader and his team from the Senckenberg Centre for Human Evolution and Palaeoenvironment (HEP), at the University of Tübingen, which will send researchers and excavators to visit the site in April.

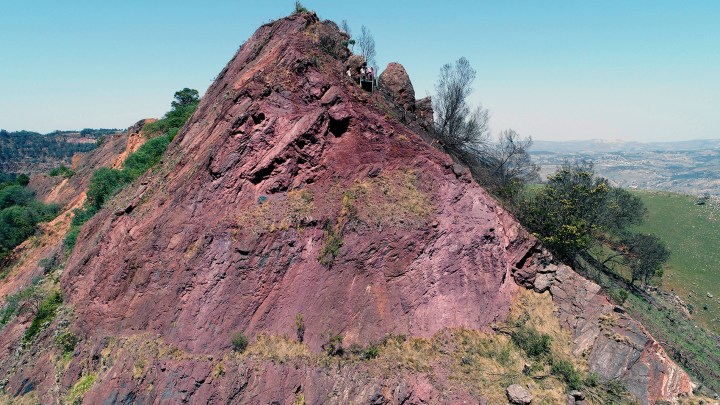

Scenery from Ngwenya Mine north over the Steynsdorp Valley in South Africa. (Photo: Bob Forrester)

Forrester is standing at the entrance to Lion Cavern, engaged in conversation with a New York TV presenter and Instagrammer. Sprawled out far below is a valley in neighbouring South Africa. On the south side of the cavern, baboons scale the almost vertical walls of an old, green water-filled quarry. The whole area, of predominantly red rock, is known as Ngwenya Mine.

“The reason I say it’s a benchmark, says Forrester, “is because it shows the first mining of ochre worldwide.” A strong claim, but one that he and his colleagues from universities in various countries aim to prove.

Red rust — from Stilbaai to Swaziland

I had first learnt of the early use of ochre far south of Lion Cavern, in Cave 13b, below Mossel Bay’s Pinnacle Point, which could be regarded as the hub of the cradle of human culture (prominent palaeontologists have posited, after well over a decade of digging, that a chunk of the Southern Cape coastline could well be the birthplace of anatomically modern humans).

Looking out from cave 13b at Pinnacle Point, Mossel Bay. Excavations in this cave and at other sites along the southern Cape — from Plettenberg Bay to Stilbaai — have resulted in the area being declared the Cradle of Human Culture. (Photo: Angus Begg)

A story repeated many times after leaving the lips of a palaeontologist has it that the fossilised bones of a musselcracker fish found at the iconic Blombos Cave paleo site are possible evidence that eating fish provided early hominins with the cognitive leap required to take them over the developmental edge into modern humans, who started making and adorning themselves with early jewellery (shells) and what could be regarded as early face paint — ochre.

With ochre deposits having been found at various dig sites along the coastline, Forrester puts Lion Cavern into perspective, pointing out that the amount of ochre found at the Blombos Cave paleo site — close to Stilbaai and dating back 100,000 years — “filled a few perlemoen shells and a painted stone”.

In contrast, some 1,600km to the north in modern-day Eswatini and dating almost 50,000 years later, Lion Cavern was an ochre mine. Forrester says the presence of a mine speaks to the “huge increase in volume” showing that ochre use was increasing exponentially. Anatomically modern humans mined the mountain purely for the pigment (haematite), not for metal.

Sangomas at a shamanic healers graduation 40 years ago. The man is wearing an ochre-coloured wig under the feathers, the woman has ochre in her hair. Both are in a state of trance. (Photo: Bob Forrester)

And the mining wasn’t restricted to the cavern. Excavations by Forrester’s colleagues and co-authors in the excavations have found that there were originally three mines and a quarry at Ngwenya, with only Lion Cavern and one other mine surviving the large-scale iron ore mining in the 20th century.

Ochre balls and chicken dust

Research published in 2021 by Bader, Forrester and their colleagues (experts from Norway, the US, South Africa and Germany), titled The Forgotten Kingdom: New investigations in the prehistory of Eswatini, highlights the significant role played by ochre in Stone Age southern Africa, in both the functional and symbolic spheres.

Bader says early humans chipped out from the mountain this clearly valuable “red rust’, aka haematite, using large tools made of dolerite — “very archaic, simply modified rock pebbles” — that had been shaped into “choppers, picks and hammerstones”. Professor Raymond Dart, the esteemed anthropologist whose discovery of the Taung skull in North West in 1924, provided a “missing link” between ape and man, had in the 1960s identified these same implements as mining tools.

The excavations and research thus far reveal the earliest intentional use of ochre to be documented far north of Stilbaai, at Twin Rivers in Zambia, dating back between 350,000 and 195,000 years. Forrester says the “ochre balls” are still valued by Swazis, and found at markets around the country.

“Filling the shells with ochre for future use is a crucial step in human cultural evolution — it shows planning for future symbolic events.”

Balls of ochre are widely sold in Swazi markets for ritual use. (Photo: Bob Forrester)

The orange ochre balls are as much a part of Swazi culture as the local favourite and thoroughly modern “chicken dust” — a reference to the dust coating thrown up by passing cars that settles on chickens cooked at the roadside on open fires. The fact that chicken-dust-flavoured potato crisps are found alongside the ochre balls at markets as well as major regional retailers, speaks to opposite ends of the Swazi cultural universe.

This ochre travelled

Firmly rooted in the historical epoch, Forrester says his excavating colleagues have on previous visits traced ochre from Lion Cavern to San paintings in the Nsangwini cave, about 20km northeast of Lion Cavern.

It was determined at a laboratory at the University of Missouri, US, that the ochre used in cave paintings 20km away came from the Lion Cavern, one of the Ngwenya sites. (Photo: Bob Forrester)

“We know the source of the ochre because we have been mapping prehistoric ochre movement across the country. This is done by taking source samples and then using spectroscopy — burning the sample in a nuclear reactor at the Archaeometry Lab at the University of Missouri.

“This technique identifies precisely the elements in the ochre in exact proportions. Tiny samples are then taken from San paintings and these are also burned in the same reactor and one can see if there is a correlation or not.”

Why only now?

With archaeologists and palaeontologists busy at sites in South Africa since the early 20th century, it is curious that significant finds like this — in particular, what are known among researchers as the “Ngwenya sites” — have remained unknown. It wasn’t always like that.

Between 1965 and 1967, South African archaeologist Peter Beaumont investigated more than 100 archaeological sites in Eswatini, excavating several of them, in the process demonstrating the deep history of hominin occupations from the Early Stone Age to the Iron Age. However, according to the Bader team’s paper Forgotten Kingdom, very little of Beaumont’s work ever reached the public after he left Eswatini in the early 1970s.

Using carbon-dating technology available at the time, the academic world simply knew that the mining of ochre had taken place about 42,000 years ago, but no more. Given the outdated nature of the testing methods, questions were asked.

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

“No archaeological excavations were conducted any more and the country faded away from archaeological prominence.“ For many years very little archaeological research was conducted in the country, until David Price Williams, quite by chance, rediscovered the archaeological potential of Eswatini.

Coming from Wales, this East Mediterranean archaeologist, with a PhD in Ancient Near Eastern languages and Classical Greek, was married to a Swazi. When visiting her family for the first time, on a mid-seventies Christmas holiday to Eswatini, Price Williams visited the Nsangwini rock art site, and according to the research carried out by Bader and his colleagues, “fell in love” (again, it would seem).

Resurrection and re-excavation

So enamoured was he with the potential implications of his “discovery”’ that he established the Swaziland Archaeological Research Association (Sara) and spent three to four months in Eswatini every Southern Hemisphere winter, along with his family, for more than a decade. According to the Forgotten Kingdom study, Price Williams conducted “exemplary research in Eswatini” documenting and excavating more than 80 archaeological sites.

When Price Williams left Eswatini in 1989, “the large Sara collection remained stored in the Eswatini National Museum at Lobamba, unseen by the archaeological community”. This was at a time when Stone Age research in neighbouring South Africa was flourishing.

Orr Tidhar, a student at Waterford Kamhlaba College in Eswatini, abseils down the cliff face at Lion Cavern, in search of further old ancient mines. Tidhar was teaching excavators how to abseil so that they could sample the newly discovered ancient mines on the otherwise inaccessible cliff face. Two more have been located. (Photo: Bob Forrester)

The resumption of excavations of Lion Cavern — which Bader calls “the tip of the iceberg” — being carried out under the auspices of the University of Tübingen, has put Eswatini’s prehistory credentials back on the world’s archaeological front page.

Where to from here?

Its importance is further highlighted by the inclusion of two young Swazi women on the research team.

Temahlubi Nkambule is completing a master’s degree at the University of Cologne in Germany, her thesis focusing on ochre use in traditional Swazi culture, while Ayanda Mabuza is enrolled for a master’s at the Tübingen, also in Germany, studying scientific archaeological dating techniques.

It would seem that momentum for Lion Cavern and the nearby Ngwenya sites to be recognised internationally is gathering pace.

“Should the oldest ochre mine in the world be declared a World Heritage Site?” says Bader, repeating my question.

“I don’t think there is any question. For sure!” DM/OBP

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.