FOOTNOTES OF HISTORY OP-ED

Letter from KZN – Churchill, the Boers and my quick-thinking maternal ancestor

Did Glen Retief’s great-great aunt save Winston Churchill’s life and thus change the course of world history? And did Churchill hide behind her skirts? Family history is sometimes an elusive truth, he finds.

‘Never forget that your great-great aunt Bourhill saved the world with her skirt hoops,” my maternal grandfather, Gerald Bourhill, always told us, leaning back in his leather recliner and sipping a glass of whisky.

He elaborated: “Churchill’s escape from the Boers made his career. That would not have been possible without your ancestor. And without Churchill leading Britain, in 1940…? You and I would be goose-stepping, right now, past the Nelspruit City Hall.”

Was he right? Without Winston Churchill, would Britain have surrendered to Germany? And would South Africa, a British dominion, then have fallen under Nazi rule?

It all seemed so speculative. Then, too, Gerald’s stories had a tendency to grow taller with the years.

The German Messerschmidt that strafed him during World War 2, on the Cairo road, eventually expanded into an overhead squadron.

The gold on our family farm, foolishly sold for a pittance, which grew into a fortune worthy of an Oppenheimer.

So, what of this ancestor hiding the young war correspondent under her petticoats, while the Boers searched the platform of Witbank Station? Not just the details seemed absurd, but even the idea itself, not least because Churchill fails to mention any Bourhills, or women at all for that matter, in his 1930 autobiography, My Early Life.

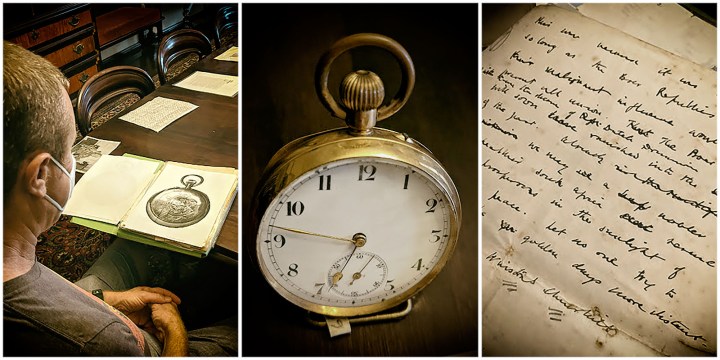

The front of the gold watch given to Charles Burnham by Winston Churchill. (Photo: Peterson Toscano)

The inscription on the back of the gold watch given to Charles Burnham by Winston Churchill. (Photo: Peterson Toscano)

Then, one summer weekday, I found myself in the Campbell Collections in Durban, examining an engraved gold watch given to Charles Burnham, 1899 business partner of one JA Bourhill – my maternal ancestor.

“From Winston S. Churchill, in recognition of timely help afforded him in his escape from Pretoria during the South African war, December 13, 1899.”

A pleasurable chill ran down my shoulder blades. As I sat in that antique dining room, smelling of dust and varnish, in that sugar baron’s mansion now turned into an art museum, I could almost feel my grandfather’s ghost next to me, saying: “I told you so.”

A signed, handwritten letter from Winston Churchill to the Natal Witness newspaper, exhorting colonists to keep supporting Britain in its war against the Boers. (Photo: Peterson Toscano)

The watch was donated to the Collections by Burnham himself, in 1955, along with a folder of Churchill-related material, which the librarians were generous enough to make available to me.

Read in Daily Maverick: “A Russian On Commando: The Boer War Experiences of Yevgeny Avgustus”

In 1899, Churchill, already a famous war correspondent, was riding in a train carrying British troops when their company was ambushed by Boer soldiers. Churchill joined the battle, braving the Boers’ bullets for more than an hour, as a supposed civilian, while directing soldiers to safety.

Detained in the Staats Model school in Pretoria as a prisoner of war, Churchill waited for the guards to look away, then vaulted over the fence. Playing it cool among the burghers wandering down Van der Walt Street, he then made his way to the Delagoa Bay Railway and proceeded to jump on an eastward freight train, which he rode until it stopped near Witbank.

He had no water with him, so he drank from rivers and streams. His only food was four bars of chocolate.

Here is how, in My Early Life, Churchill described stumbling, hungry, thirsty, and exhausted, into the home of John Howard, manager of the T&DB coal mine, which was co-owned by my Bourhill ancestor:

“Will you help me?”

There was another long pause. My companion rose from the table slowly and locked the door…

“Thank God you have come here! It is the only house in twenty miles where you would not have been handed over.”

Howard and his workers did conceal Churchill in an abandoned mine shaft. Later, when the searches launched by the local Boer field cornets died down, Churchill moved to a back room of the mine office.

In My Early Life, Churchill ascribes the plan to smuggle him across the border hidden among wool bales to a Mr Burgener, a nearby “Dutchman” who was “well disposed to the British”.

This appears to have been an effort on Churchill’s part to protect the identities of his real helpers.

Read in Daily Maverick: “A Karoo Graveyard: Thoughts, mist and memories”

According to a 1923 interview Charles Burnham gave to The Star, included in the Campbell Collections folder, it was in fact Burnham who hatched the plan for him to accompany a freight train of wool to Delagoa Bay.

It is here, too, that my maternal ancestor enters the official record. Burnham told The Star that the plan could never have worked without the silence of the wife of his business partner:

“In view of the fact that I was running a big risk… I felt it incumbent on me to take Mrs Bourhill into my confidence, and I must say she loyally respected it… She expressed a wish to see Mr Churchill before he left the property, and I myself took her to the mine. Mrs Bourhill had a conversation with Mr Churchill and wished him success with his venture.”

Exterior walkway at the Campbell Collections in Durban. (Photo: Peterson Toscano)

So, then. A mine office instead of on a train platform, and instead of protective skirts, bales of wool.

But still, then: a grandfather’s story with a kernel of truth in it.

As Gerald Bourhill himself used to say, whenever reality surprised him: “Well, bloody hell, I haven’t heard anything like that since Granny fell off the bus.”

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

The rest of the escape, which is related in the 1923 interview, roughly aligns with Churchill’s own published account. Burnham’s interview does make it clear that his black workers played a significant, unsung, role in building Churchill his “cave” among the wool bales, and then joining Mrs Bourhill in keeping mum about the plans.

Read in Daily Maverick: “Why Soviet troops fought Nazi forces to Boer War tunes”

As Churchill travelled towards today’s Maputo, Burnham relates bribing Boer officials with whisky and cash to keep the wool bales moving east. Clearly, irregular income on the South African Railways did not begin in the Zuma-Molefe era.

Churchill spent a night in Waterval Boven, hidden in Burnham’s wool. The next morning, Burnham describes cleverly diverting a Boer soldier who was leaning against the part of the carriage where Churchill was hiding by offering him a cup of coffee.

When the train arrived in Delagoa Bay, Burnham accompanied Churchill to the British Embassy, where he was cleaned up and put on a steamer to Durban the same night.

There, “the cheering was continuous and enthusiastic”, reported the Natal Mercury on 23 December 1899. “Amid it all could be heard voices shouting, ‘Well done, sir’, and such like complimentary exclamations.”

The rest is well-known history. Britain beat the Boers, then joined with their erstwhile enemies to exclude blacks from political power in 1910. Having lost his first election bid, Churchill leveraged his celebrity to win election to the House of Commons, in 1900. There, he eventually made the speeches that helped defeat Hitler: “We shall fight them on the beaches…”

The Campbell Collections maintains a folder of Churchill-related documents, which they made available to the author when he visited. (Photo: Peterson Toscano)

What accolades did Gerald Bourhill ever receive? A farm foreman who dropped out of school in sixth grade, Gerald’s stories of his own military service, fighting Rommel’s tanks in the Sahara, often cast himself in a Churchillian, heroic light.

Read in Daily Maverick: “

“Letter from KZN: Finding common ground with Piet Retief in the great, royal city of Umgungundlovu”

“Letter from Limpopo: Once upon a time, in lands of gold and stone”

Along these lines, he told us he worked as one of the chief aides to General Dan Pienaar, head of the South African forces. Supposedly, he was carrying a classified package for Pienaar, that moonlit night the Messerschmidt, or squadron of them, attacked him, prompting him to hide in the dunes.

On another night, Gerald claimed to have shared a premonition with the general.

“Don’t get on that plane,” he told his boss. That was another instant a Bourhill might have helped the world, since if Pienaar hadn’t died in an aviation accident an hour later, the Allies might have triumphed sooner.

But there were no medals, no celebrations or parades for this working-class man who suffered lifelong from post-traumatic stress disorder as a result of his war experiences.

Read in Daily Maverick: “Rock of ages: Wartime graffiti reveals the tragic story of outlaw Boer women and children”

Admittedly, he was not as forgotten as, say, the nameless black workers who built Churchill’s hiding place.

Nevertheless, his core experience as a manual labourer was of having his talents, intelligence and creativity overlooked.

Entrance to the Katie Campbell Library, maintained today by the University of KwaZulu-Natal. (Photo: Peterson Toscano)

The Campbell Collections folder contains a printed programme for Churchill’s grand memorial service in Cape Town in 1965.

By contrast, when Gerald Bourhill passed on in 2003, his was a small, modest funeral, attended only by friends and relatives.

Perhaps this is why we as individuals as well as nations tell ourselves stories of our own specialness, tales we need to hear and believe, narratives that live on in the memories of our loved ones and stand as bulwarks, however fragile, against time’s erasure. DM

Glen Retief’s The Jack Bank: A Memoir of a South African Childhood, won a Lambda Literary Award. He teaches creative nonfiction at Susquehanna University and recently spent a year in South Africa as a Fulbright Scholar. He gratefully acknowledges the assistance of Eddie Bourhill, Peterson Toscano and Senzo Mkhize in researching this article.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Facinating story thank you for sharing

A well-weaved story, thank you.