ESCAPE

A Steamy Affair: The locomotives of the Karoo and the men who stoked and drove them

Loco drivers, their firemen and their gleaming steam trains have a special place in the timeless chronicle of Karoo legends.

Spring, 1988: In days gone by, when De Aar was a full-steam-ahead kind of town, the locomotive drivers would yank their whistles late at night as they approached the Karoo settlement. Each driver would have his own signature tune, and his family living in the town would know it well. They would prepare for his return the minute that whistle went off.

To the general public of De Aar, the particular lilt of a loco whistle would indicate the way the Karoo wind was blowing that night – and what kind of weather they could expect the next day. Nearly everything in De Aar revolved around The Colossus, the steam locomotive. For more than a century, the railroad tracks sang the praises of these huge metal dragons criss-crossing South Africa – and meeting in this Northern Cape town.

National steam no more

Steam has disappeared from our railroad system, except for the occasional heritage train experience. And then the sight of a loco in full toot across the veld is a wonderful hit of nostalgia.

A long-standing community of locomotive drivers and stokers retired to De Aar in the 1980s, perhaps to be close to one of the country’s last refuges of the steam train.

A man like Piet Claassen grew up next to the tracks, in a little railway house in Kranskuil. His father worked on the railways, and so young Piet joined the SAR&H as well. That was the way, then. “If your father was a railroad man, you became one as well,” said this huge 49-year-old senior staffer at De Aar Station.

“The hissing of the steam, the smell of the oil – that whole machine has a life of its own.” Image: Chris Marais

“On the tracks, the locomotive is your first love – you are more at home in the caboose than out of it.” Image: Chris Marais

Piet learns to stoke

When Piet was 16, he went to Keetmanshoop in then-South West Africa as a station cleaner. It was the only job available on the railways, and he spent six long months cleaning trains and learning the time-honoured art of stoking.

One day a stoker fell sick and the supervisors chose someone from the yard – Piet Claassen. The driver was one Willem Rossouw, with 30 hard years’ experience.

“Willem was a good man. He knew his train well. If you couldn’t keep the steam flowing, he did it for you.”

Piet Claassen became Willem Rossouw’s regular stoker, the “driver’s eyes on the left-hand side”. He would fire up the loco and he would keep that fire burning for 21 days. Then the steel, brass and copper machine would have to be meticulously serviced, cleaned and polished.

“Even out on a trip, we would polish the train – by the time it pulled into a big station, it shone like a jeweller’s shop.” Image: Chris Marais

The sound of the steam

There were a hundred things to learn: water levels to be kept constant, steam pressure to be monitored, the fire kept “just right”, the sound levels sweet and on an even keel.

“The sound in a steam locomotive is very important. And there was always a lot of it. The funny thing was, we used to sit in the caboose and talk through all that hissing and chugging. We somehow heard each other, or read each other’s lips – it was strange.

“If we were sitting somewhere else, with that level of noise going on, there was no way we could hear normal speech. I suppose the old ear just tuned the steam sound out.”

He described the different sounds made by the loco on a run: “You’re going up a steep hill in 425 tonnes of steam locomotive. That old thing talks to you, you work on the sounds and the cadences. And then on a straight, with speed, there comes that smooth, rhythmic chug – and you’re at one with your train.

“The locomotive sounds are rooted in you. You learn to pick up the smallest abnormality. And the sounds come from everywhere: the stoking, the wheels, the regulator, the valves, the steam release.”

Steam in the sheds – time for meticulous maintenance. Image: Chris Marais

“Once the steam is in your blood, you cannot keep it out. When a loco beats well, you get chicken bumps on your body.” Image: Chris Marais

There were a hundred things to learn: water levels to be kept constant, steam pressure to be monitored, the fire kept “just right”, the sound levels sweet and on an even keel. Image: Chris Marais

Boel rides along

When Piet Claassen finally became a loco driver, he took on two habits that soon became his trademarks: a constantly-lit pipe filled with Boxer tobacco and a dog called Boel. The dog would sit at his feet in the caboose through all his long trips, traversing the Karoo at night, sleeping over in the Kimberley Station rest rooms, and keeping him company on his long shifts away from home.

“I smoked a pipe because when you light a cigarette in the cabin, the wind smokes more of it than you do. And the dog, well, one day the loco inspector discovered him up there with me. Boel had to stay home after that.”

He said the crew stop-overs at the rest rooms across South Africa were an essential element of the fun in the job.

“You prepared your own food in these rest rooms and were supposed to catch some sleep before your train continued. But you actually ended up with some of the other crews, swapping stories through the night.”

“The rest rooms were fun. You ended up with other crews, swapping stories through the night.” Image: Chris Marais

Oom Apie remembers

Abraham Isaac Ludwick goes by the name of Oom Apie. He is retired and living in De Aar in a house that was once not too far away from the night whistles of the incoming locomotives. Oom Apie Ludwick always wanted to join the army but he was too short, he says.

“It was just after the Depression. I became a coal trimmer with the railways. Then I became really interested: I realised these colossal machines would show me the world one day. I became a stoker at 23, a driver at 30.”

As a stoker, he worked with two drivers, Vlakhaas Davis and Fred Budd. He stoked from Kimberley to Beaufort West, Keetmanshoop to Luderitz and then up on the Johannesburg run. “In those days, the drivers had no mercy for you. Today, they love you.”

Hunting from the footplate

On the Southwest runs, Oom Apie and his stoker would always take a rifle along, rolled up in canvas at the back of the cabin, to shoot “something for the pot”. When they were on a goods trip, it was possible to stop and hunt for a short while.

“One time, Koot Blaauw – the stoker – shot a gemsbok right between the eyes. Between us and the conductor, we tried to load it onto the train. The sun was just going down, and I switched on the train headlights. Here comes this police sergeant and his constable, from nowhere, it seemed to me.

“We told the sergeant we had just run over the buck, and that we didn’t want to see it die a slow death so we slit its throat. He helped us load it, and we butchered it. Then the sergeant took me aside and said:

“’Oom Apie, if I didn’t know you I’d arrest you. Next time you run over a gemsbok, don’t hit it precisely between the eyes!’

“We gave him a haunch and he left.”

An old guy admiring an old steam train in action – a perfect pairing. Image: Chris Marais

Running Fowl of the Law

Another time, Oom Apie was working with a certain Gwar Liebenberg on a trip and they shot a guinea fowl for the pot. The bird was duly cleaned and dropped into the fire bucket. When they reached their rest stop at a tiny depot called Usikus, they found a large pot and began cooking the guinea fowl in a stew mix.

“We always travelled with some potatoes and onions, just in case. Anyway, we left the guinea fowl cooking overnight, and the next morning I saw this policeman entering the rest room.”

Oom Apie told Gwar to prepare the train for their speedy departure. He would rush in and rescue the fowl from the cooking pot before the policeman could catch him.

“But the policeman stayed and sat with me at the table. I couldn’t wait for him to leave.” So the two crusties sat there making small talk, eyeing each other. Eventually, the conductor came in to call Oom Apie, and the desperately hungry driver thought, that’s it! Policeman or no policeman, I’m taking my fowl!

As he rose, so did the anxious policeman. Together they walked to the pot. And each man grabbed his own guinea fowl and left in a separate direction from the other.

South African Baby Boomers who rode the once-incredible national railway system will all remember the lonely sidings late at night, in the middle of nowhere. Image: Chris Marais

Breakfast fresh from the furnace

In some circles, it is believed that if the Voortrekker invented the braai, then the train men perfected it.

“We used to take the shovel and load eggs, bacon and sausages onto it. After a short stay in the furnace, the aroma of the best breakfast in the world would filter through the loco. Likewise, coffee brewed in a steam locomotive cannot be beat.”

Oom Apie Ludwick has some taped memories of the Era of Steam, mostly friends of his who had recorded their experiences for posterity. Playing the tape, you hear those old voices bringing back the past.

“… you came to know the spade. Placing the coals carefully onto the furnace, 12 hours a day. You were exhausted, but then that was life. Other stokers would teach you the spade, you would get better with the days.

“Once the steam is in your blood, you cannot keep it out. When a loco beats well, you get chicken bumps on your body. The hissing of the steam, the smell of the oil. That whole machine has a life of its own.”

Taking a shine to a loco

And despite the freezing arrivals in De Aar, when snow covered the tracks and cold steel burned the unprotected hand, the winter nights on the Karoo prairie with the wind howling like a banshee and the blistering hot days in the Southwest, the steam experience crept into their souls.

Said Oom Apie: “Some of the stokers would spend three hours shining up their trains before departure.

“At home, you love your wife. On the tracks, the locomotive is your first love. At times, you are more at home in the caboose than out of it. To see that light smoke trail from a Class 25 loco, to hear the sound as it goes uphill with the driver opening up the regulator ever so slightly – that is mother’s milk to a train man.”

Read in Daily Maverick: “Karoo oddities – tales from the quirky, magical heartland of South Africa”

The locomotive graveyard

The steam locos all carry feminine names: Marjorie, Hessie, Anna, Elna, Eliza, Lizette, Ina. They were named after crewmen’s wives and daughters way back then. Piet Claassen has a loco named after his daughter Selma – but it’s also destined for the De Aar steam train graveyard.

To walk around that graveyard is the poignant experience that still brings thousands of international steam train enthusiasts to De Aar every year. The locos are stripped of their name plates, copper pipes and brass fittings.

In the heydays of South African steam, the locos were named for the wives and daughters of their drivers and firemen. Image: Chris Marais

They stand, stark and bleak, as the wind howls through the empty cabins. The locomotives are lined up end to end, waiting to be purchased and shipped out to the front lawn of some South African small town hall, or simply butchered for scrap by blowtorching.

Nearby, is the rail yard. The best time to be there is at dawn, when soft light reflects off the steamy shanks of the gleaming machines. It’s obviously a sight and sound experience because with a shiny locomotive comes its incessant steam-breathing.

The working locos testify to the pride of their crews.

“We kept them cleaner than our own clothes or our food boxes,” says Oom Apie. “Even out on a trip, on a slow uphill, we would get out and polish the train. By the time it pulled into a big station, it shone like a jeweller’s shop.” DM/ML

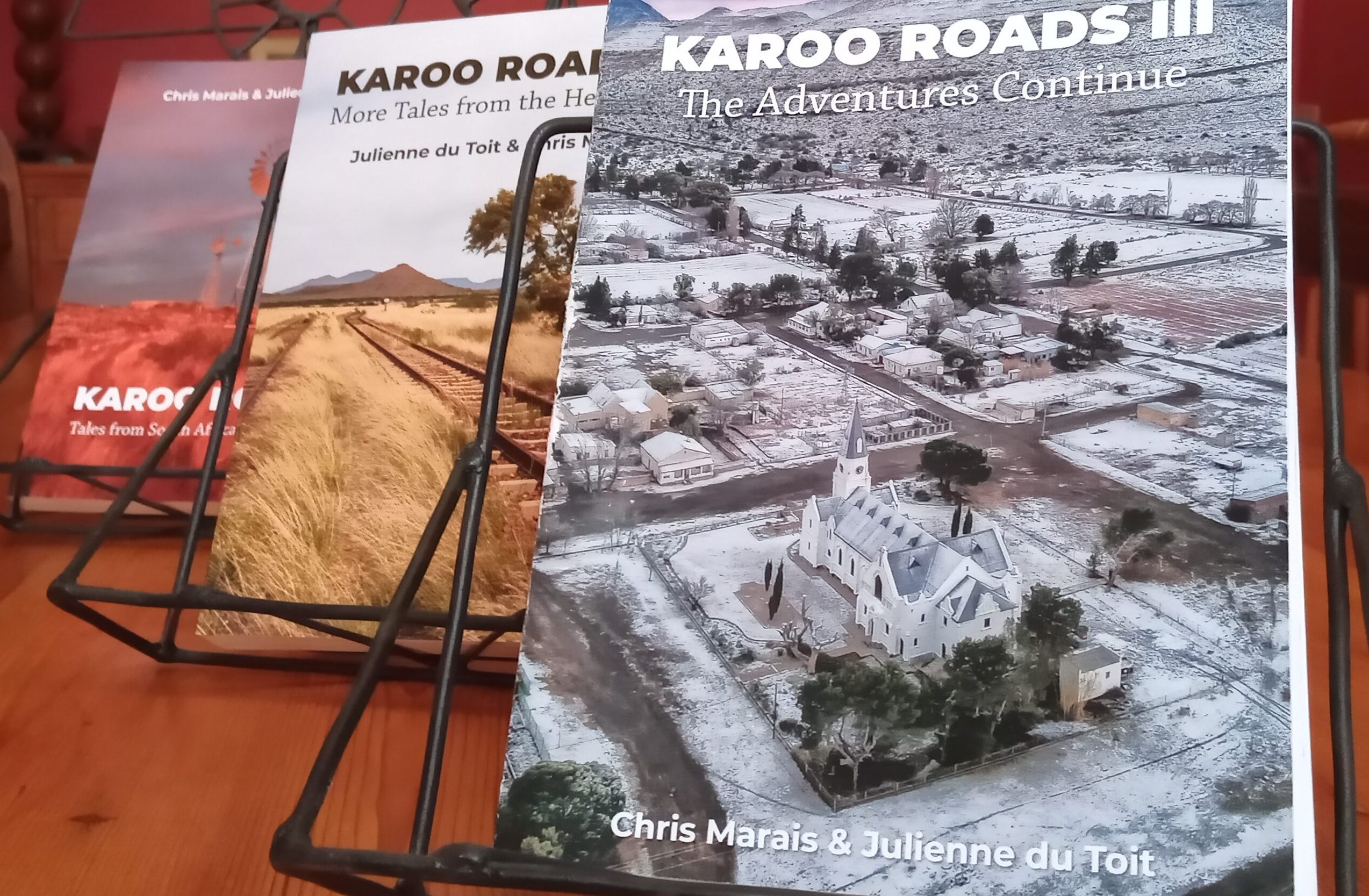

This is an extract from Karoo Roads I – Tales from South Africa’s Heartland, by Chris Marais and Julienne du Toit.

‘Karoo Roads’ Collection. Image: Chris Marais

For an insider’s view on life in the Dry Country, get the three-book special of Karoo Roads I, Karoo Roads II and Karoo Roads III (tales of the Heartland with monochrome images) for only R800, including courier costs in South Africa. For more details, contact Julie at [email protected]

The accompanying photographs were shot on location at Sandstone Estates outside Ficksburg, Free State. Check www.sandstone-estates.com for more details on the 2023 Sandstone Easter Steam Festival.

Absolutely brilliant ! It takes me back to my school days at Union High in Graaff Reinet. I would catch the train home for the school holidays. Two days from GR to Margate on the South Coast of Natal. All of it powered by steam.

The railway to Rhodesia went through our farm. We all went back and forth between the farm and boarding school in Kimberley on the train. The boys kept a lookout for the smoke from the approaching train from the roof of our farm house. There was then a frantic rush for the station wagon and the siding. One day we cut it a little fine. Lots of hooting and flashing headlights brought the train to a shrieking halt and a relieved father was able to divest himself of offspring and luggage.

On Christmas day the Rhodesian mail was a sight to see; brass dome and piping flashing in the sunlight and two karee trees jammed at angles into the cowcatcher in front. The driver would let off steam and we would run barefoot through the cool mist. Such a treat on a scorching hot Northern Cape day.

All trains including the white train stopped to take on water at our local siding Devondale which even gave our family an opportunity for a late night personal chat with the king and queen of England on their 1947 tour of South Africa.